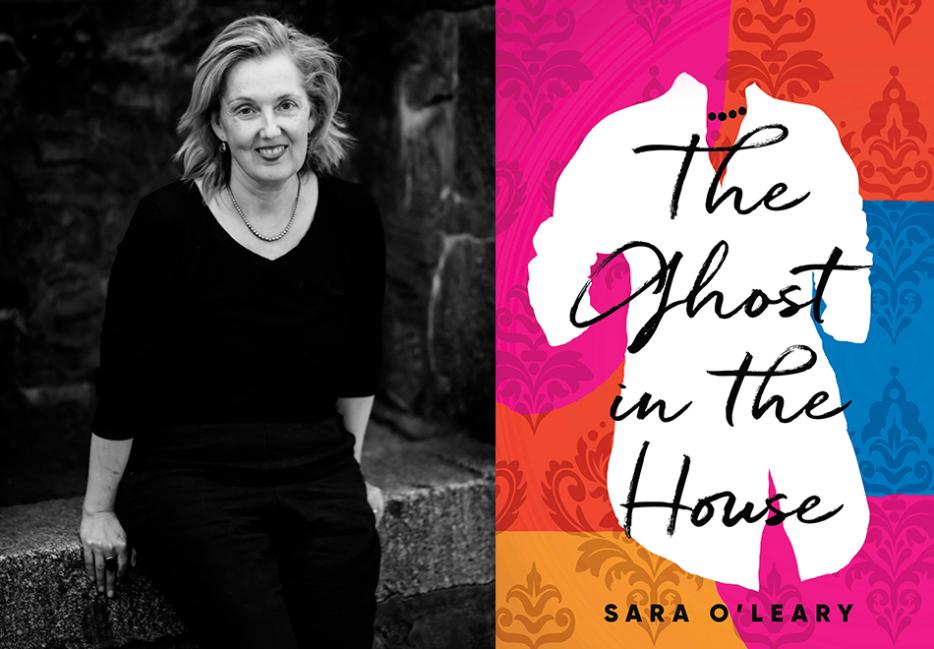

Sara O’Leary’s debut novel The Ghost in the House (Doubleday Canada) is a dark comedy about self-awareness, existential dilemmas, and life after death (especially the sort of life that has somehow kept going and wants you to bear witness to how everything has rearranged itself to cover up the gaps you left behind).

Thirty-something Fay, the novel’s narrator, realizes that instead of her life being on the cusp of something bigger, it has abruptly ended without her permission. Her husband, Alec, has a new love, and teenaged Dee—who isn’t sure if she wants to belong to the living or the dead—is Fay’s key to communicating with the real world.

Also a screenwriter, writer of short stories, and children’s book author, O’Leary’s dialogue delights in what our miscommunications say about ourselves. She uses short, shimmering sentences to play a who’s-really-been-left-behind riddle from chapter to chapter with the reader.

What follows is less a coming-of-age story and more a coming-to-terms-with that slyly upturns the traditional who’s-who of ghost stories. “Fay is 37 when she dies and assumes that she still has lots of choices left to make,” O’Leary says. The novel pokes and prods at the denial that often comes with grief, “reconciling yourself to…the fact that life continues even when you’re gone—a sort of It’s A Wonderful Death scenario.”

Sara and I spoke in the lead-up to the book’s release, and unpacked the responsibility, desire and motivations behind processing life (and death, and grief) by writing ghost stories.

Nathania Gilson: What sparked your desire to write a ghost story?

Sara O’Leary: I’m not sure I believe in ghosts, although I’ve lived in a number of haunted houses. The characters in The Ghost in the House are fully imagined but the house itself is the one I used to live in before leaving Vancouver, and I think of it like a lost love.

I’ve always really been interested in girl-meets-house stories. Manderley, the setting of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, was based on the house Menabilly that she discovered and brought back to life. Similarly, Lucy Boston bought a house called The Manor and used it as the setting for her Green Knowe books. Both are stories of hauntings and in both cases the house itself becomes a character in the story.

I’m not particularly frightened of my own death but I do find it somehow shocking that a person can be in the world one moment and then gone. How can that be? A very dear friend died the year we both turned 36, and while I face constant reminders that I am growing older, she stays fixed in time and now seems impossibly young to me. All the things she was planning to do, all the places she was going to go, the children she wanted to have—all of that went with her.

I think it’s fairly common after losing someone to have that dream where they are suddenly there with you, saying that no, no, it was a mistake, and that they never really died. Or sometimes it’s not as explicit as that—just a dream where you walk into your kitchen and there they are, sitting at the table. I suppose that’s what I wanted to explore—how something that’s finally one of the only certainties in life can feel so terribly unreal. And because of my innate sense of the absurd, it made sense to me to tell the story from the perspective of someone who had just died.

It’s hard to talk about all this without making the book sound terribly dreary and woe-some, and I really hope it’s not. It’s a story about dying, yes, but I think also about growing up, and truly loving someone, accepting (as my mother used to tell me when I was a child) that life is not always fair.

There’s a constant sense of negotiation and bargaining throughout the novel: the desire for more time; wanting to be heard and seen; escaping loneliness. Even sometimes, expressing or acting out on pettiness because of the shield that invisibility and not being “in” the world affords you. What drew you to exploring these feelings from a female character’s point of view?

As someone who writes for children, agency is something that naturally interests me. These two streams of my writing crossed over when a book I was writing set in a dollhouse started showing up in the house in my novel. There is something genuinely unheimlich about dollhouses that seemed to fit this story, but they are also very connected to agency. Rumer Godden wrote, “It is an anxious, sometimes a dangerous thing to be a doll. Dolls cannot choose; they can only be chosen; they cannot ‘do’; they can only be done by.” I think that Fay’s sense of powerlessness is paralleled by that of the thirteen-year-old girl suddenly inhabiting her house. Fay sympathises with Dee’s feeling that decisions are being made about her life, but not by her. They both feel that they cannot do but only be done by.

It felt natural to tell this story from the female perspective. And I think Fay struggles—as many of us do—with the notion that we should be able to have it all. There’s that whole art monster question from Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, whether it’s possible to be both mother and artist. This got me thinking about how sad it is to forgo one and never achieve the other. Fay is full of dreams and aspirations and plans for the things she always expected to have time to do, and I was interested in exploring how it would feel to see all that vanish before your eyes.

What would you regret? There’s that Raymond Carver line: “And did you get what/you wanted from this life, even so?” Fay feels she has been cheated. All her bargaining and negotiation is in answer to that, but, ultimately, it’s a futile gesture. She’s had her life and all that’s left to her is a final act of grace.

Being embodied is a theme in this novel—specifically, being comfortable in the body you’re given and navigating the world with confidence. Fay seems to struggle with this. What work do you turn to when looking historically to how women’s sense of autonomy and confidence has been expressed?

When I still thought I might pursue an academic life, my main area of interest was writing by female modernists, and Djuna Barnes in particular. There’s a little nod to Nightwood in the first sentence of the novel. In fact, you’ve just reminded me that at one point I started a novel set in the 1920s about a girl from Unity, Saskatchewan who runs away to Paris after her father tells her she can’t stay out until midnight on New Year’s Eve. Maybe I’ll go back to that!

I do love that period, and interestingly, it was a time when spiritualism was very prevalent. Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows looks at that in such an interesting way, and I think a similar mixture of doubt and belief found its way into The Ghost in the House.

The Fountain Overflows is also a book about agency, which is certainly part of its appeal for me. I share the attitude of the main character, Rose: “She found childhood an embarrassing state. She did not like wearing ridiculous clothes, and being ordered about by people we often recognized as stupid and horrid, and we could not earn our own livings.”

In my story, Dee and Fay both exhibit frustration with their lack of autonomy over their own lives, and as Fay says, “The only good thing about being thirteen is that unlike being dead, it doesn’t last.”

Navigating the world in a female body naturally presents its own set of challenges, but Fay has moved beyond her body, which is in itself a form of freedom. There are three poems I think of as the invisible epigraphs to the book: Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” Stevie Smith’s “Away, Melancholy,” and Emily Dickinson’s “The Things that never can come back, are several.” The movement in these poems follows aspiration, loss, and ultimately acceptance, that I think (hope) is also the arc of the novel.

It was interesting to me how introspective Fay is for a ghost. She’s wondering how she compares to other ghosts who may or may not be stuck haunting the houses they used to live in; wondering where she sits on the Kübler-Ross grief cycle. What role did humour play in upturning our idea of what a ghost story could be?

For me, humour plays a role in everything! There’s always been something intrinsically comic about this story to me, although I think I lost several of my favourite jokes somewhere along the way. At one point I had Fay examining her inability to shake off her attachment to her house and possessions by musing: “If you can’t be Zen about things when you’re dead, then when can you?”

Is Fay introspective for a ghost? She does spend a lot of time in the past, but I imagine ghosts have a lot of time on their hands—the original self-isolators.There’s also the question of whether Fay is really a ghost at the beginning of the novel, or is imagining she is.

The burst of electrical activity in the brain at the time of death could explain that old truism of one’s life flashing before their eyes. For me, it’s more interesting that the brain’s desire for narrative might mean that those moments are spent constructing an alternate reality—in this case one where life goes on, but you don’t go with it.

I do think at the beginning of the novel Fay is guilty of a sort of solipsism that may be what held her back in life and that she initially views the new inhabitants of the house as projections of herself. She does have difficulty in reaching the acceptance stage of the grief cycle, but perhaps it is different when the one you are mourning is yourself.

The people who can see and talk to Fay while she’s a ghost are not always kind to her. How are ghost stories a way to explore resentment or unfinished business that might not have been possible otherwise?

Are we kind to the dead, I wonder? Or do we often resent them—after all, they left us, didn’t they? Perhaps we would extend to a ghost the same selfish attitude we are often guilty of when encountering those who are bereaved or facing a terminal diagnosis. We’re all too often frightened of our own mortality and can be clumsy and churlish in the face of reminders. Ghost stories appeal to us because of that frisson of fear and unease, and the reflex to “other” Fay as a ghost seems natural because the living are territorial about things like houses and bodies.

In Fay’s case, she’s a revenant who finds that there’s no longer room for her in the home she has left behind. Her husband has married a woman who in many ways seems like a perfected iteration of Fay, and with her she brings a child to take the place of the one that never was. The only way Fay can fully return is by displacing others, and so if the living beings in the house are sometimes unkind to her, then it is partly in the face of her refusal to accept the natural order of things.

For novelists wanting to delve into these dark, difficult waters, how can they approach the challenge ahead of them?

As writers, do we have a responsibility to the dead? If so, the responsibility of the fiction writer is necessarily different from that of the journalist who must concern themselves with facts, or that of the memoirist who is staking a claim against mortality. Of course, our own death is the one thing we cannot write about experientially (apart from those heaven tourism books that purport to describe life after death) and so it follows that books about death are much more likely to be witness accounts.

When I think of books about death, I think of Sonali Deraniyagala’s Wave, written about the loss of her entire immediate family in a tsunami. It is difficult to be so privy to someone else’s grief in the face of an almost unimaginable tragedy but I came away from the book feeling enriched by the enduring quality of the different forms of love. And one of the more moving pieces of writing I’ve read is Lucy Kalanithi’s epilogue to her husband Paul’s When Breath Becomes Air in which she talks about facing death in our death-avoidant culture. It seems to me in each of these cases the impulse in writing about one’s loved ones must be to keep them alive just that little bit longer.

So where does that leave writers of fiction? I don’t think it’s possible to answer that without considering the larger question of the function that fiction serves. C.S. Lewis wrote “We read to know that we are not alone” and I’ve always felt that to be true. That is also perhaps as good a reason as any to write—as I chose to do—about grief.