By the fourth or fifth time my phone’s trill trailed off into a void, I could feel interviewer’s panic building. Not only was I unable to ask Chris Ware any questions, I didn’t even know why. Eventually I found out that I’d been given the wrong number, and instead of calling the great cartoonist at his home in Chicago-adjacent Oak Park, I was pestering some empty corner of a former residence in the city proper, an apartment building that inspired the setting of his new graphic novel Building Stories. My mood of bleakly comical desperation would not be unfamiliar in a Ware book, either.

Published this month as a huge, weighty box, Building Stories collects 10 years and hundreds of pages of comics into 14 distinct, non-linear fragments: skinny pamphlets, a bound children’s book, oversized broadsheets, each one dovetailing elegantly with its contents. If Ware’s precise line and meticulous sense of design have tended towards formalism, this must be formatism. The world of Building Stories isn’t smothered by its elaborate packaging; from an elderly daydreaming landlady to the sentient, talkative, slightly pompous-sounding edifice itself, a certain wistful resolve abides, ambivalent but vivid.

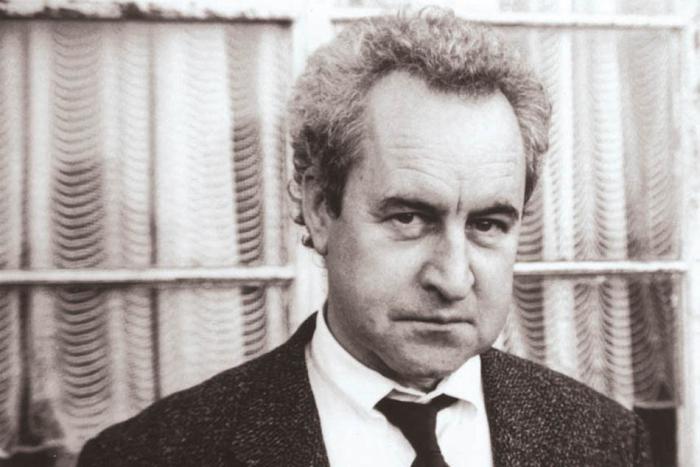

The main character, an unnamed woman who grows older or younger depending on one’s circuit through the box, seems strikingly different from the generations of father-stunted sons in Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth. She loses her leg and ends a pregnancy, nurses mildly fantastical hopes in between moments of casually brutal self-criticism, regrets abandoning her artistic endeavours no less even as she later takes to motherhood. She’s witty, then lonely, then witty about being lonely. In recalling and rearranging the scattered details of her past, she finds a kind of slippery contentment. Near the end of Alan Hollinghurst’s novel The Stranger’s Child, an aged interviewee laments: “He was asking for memories, too young himself to know that memories were only memories of memories.” Ware and his protagonist both understand that a memory of a memory is sometimes the best grist at hand. When we finally spoke, he was short on time, apologetic, and happy to talk more via email.

Given the monumental nature of the final book, or box, I’m curious about when and why you decided to collect the Building Stories material in this way.

Rather than a traditional book, with its implied through-line and convenient beginning and end, the structure of Building Stories is one kind of attempt to hopefully reflect the way we remember stories and the details of life. That is, rather than imagining every aspect of our lives as thorough, well-thought-out chapters and resolutions, we’re also able to approach these memories from all sides and all times at once; we can take them apart and put them back together again to perpetually retell the stories of ourselves and of others. As well, I’d simply hoped to make something beautiful (though such value judgements are always up for question, needless to say.)

It’s not a single story, either, but many potential ones; you can generate a somewhat different narrative depending on the order you read each segment in. Were you thinking of the indeterminate compositions that John Cage and other composers experimented with, or, say, Nabokov's Pale Fire?

I don’t believe there are any variant narratives depending on what order one reads the books in, but there are variant narrative sensations (such as whether what one is reading is the present or the past, which is an experience I think we all have to a greater or lesser degree while lost in thought.) I’d hoped to get at the feeling of once being a young, single person and trying desperately to imagine what it would be like to be a parent—and the nostalgic inverse of that equation, as well. Somehow, all these versions of ourselves coexist in our minds and memories, both as memories and possibilities, and the memories of possibilities.

And yes, Pale Fire was a tremendous influence and is one of my favorite books, assigned by my sophomore college English professor Mr. Garrison; it changed my life. To one degree or another anyone who reads that book I think yearns to create a “thing in and of itself” that it so deftly and casually weaves, and in a similar way—though one I don’t want to give everything away here—hopefully Building Stories does, too. Just not as well.

This is also your first book focused on women—there’s boyfriends and husbands, but the only male narrator is Branford [a hapless cartoon bee, perpetually flagellating himself for sexual fantasies involving the hive’s queen and her colossal ass], our comic relief, and he lives in a literal matriarchy. I thought the world of the human characters was deeply un-masculine as well. Did you worry about how to believably and sensitively represent these women? I’ve been reading a lot of interviews with the writer Junot Diaz lately, and in one of them he said: “The one thing about being a dude and writing from a female perspective is that the baseline is, you suck.”

Well, that’s one way of putting it. I commented to my wife recently that having my mom and my grandmother as my central role models meant that I’d essentially been “raised by women” and she laughed and said that I made it sound as if I’d been raised by wolves. But I know I benefitted greatly. There is absolutely no single aspect of one’s personality that is more important to develop than empathy, which is not a skill at which men typically are asked to excel. I believe empathy is not only the core of art, literature and music, but should also be at the core of society, from ethics to economics.

I wrote this note as grist for a possible followup questions, but maybe it can live on its own...I was especially struck by your delineation of the ways women are made to feel constant anxiety about their bodies, down to the protagonist acidly noting her “skinny” and “fat” artificial legs.

It doesn’t take an especially shrewd cultural critic to see the slings and arrows aimed at women from every corner of our “culture” every second of every day. I especially love it when some cosmetic or clothing company makes a big to-do about some ad campaign that purports to present “women as they actually are,” though generally that only means unPhotoshopping the two or three pounds that we’re used to seeing.

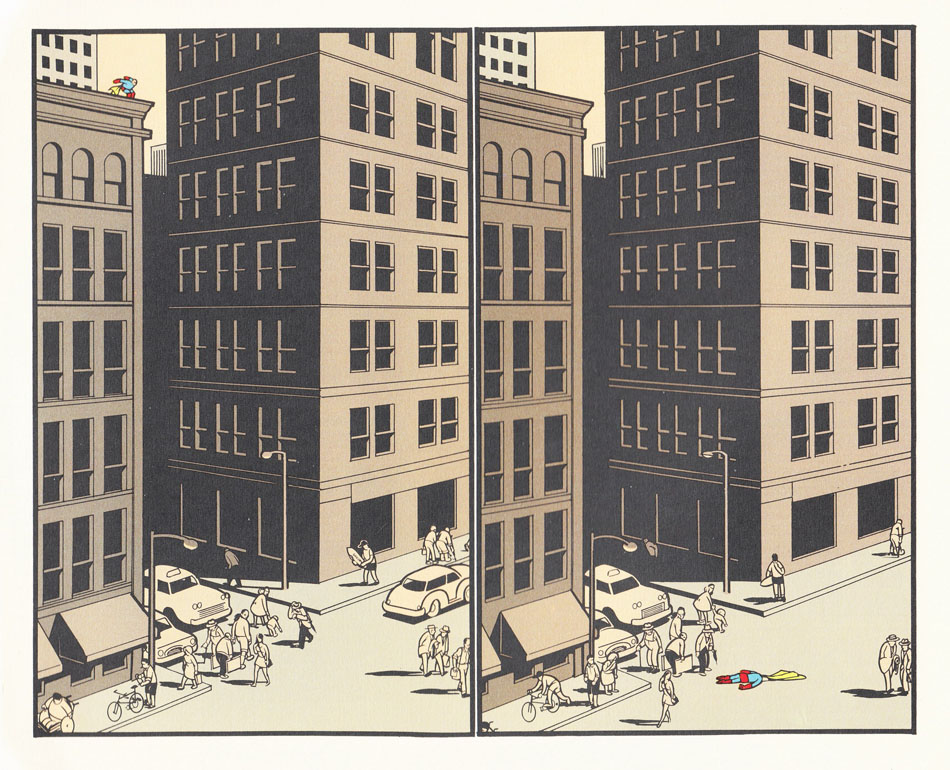

Returning to autocritiques one more time, there’s a creative writing class where some woman sniffs at the main character’s story, which is also your story: “...and with the stiff style the overall effect is very pedantic...” It’s funny, but it also made me wonder: do you ever struggle to get an elaborate design laid out without overwhelming the page? At certain points, I almost thought you had expanded the language of comics out of simple necessity; the use of planes when Branford finds himself trapped inside a pop can, for example, or that astonishing sequence where the landlady “pins” and repins herself as a paper doll, both frozen and unstuck in time, a bit like Richard McGuire’s “Here.”

Richard’s “Here” strip is one of the great watersheds of comics and it changed my (and many other cartoonists’) lives. I try to cite it as much as possible because I feel I owe him such a great esthetic debt. With that work he discovered the heretofore-unknown “z” axis of comics, and I not only employ that in what I do, but try to follow his example in stretching the boundaries and possibilities of what I’m aiming for, as well. “Here” will be published by Pantheon in its final graphic novel form in 2014, I believe.

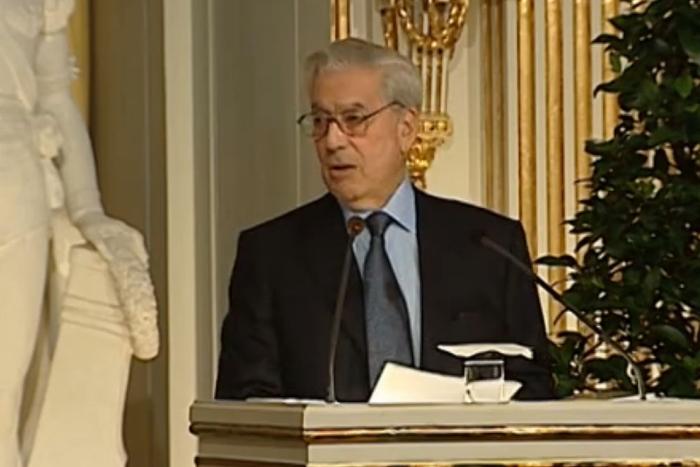

Building Stories originals have gone on display at several galleries recently. As someone who tends to be intensely, eloquently self-critical, did you feel any trepidation about that?

Sure; I sort of gave up on galleries and started only focusing on books years ago, so any shows of drawings I have I now are presented more like a natural history museum might show them than as an art museum might; I certainly don’t think of the gallery as a “challenging space” like I was encouraged to in art school. Such challenges, if any, are up to the book entirely, which should be as affordable to the greatest number of people as possible. Fine art is generally not an affordable thing, and I found and still find that aspect of it extremely off-putting, not just plain offensive. The reach and power of art shouldn’t be determined by how much a hedge fund manager is willing to pay for it. Thus, any drawing that I sell is really more of a relic of the printing and thinking, not a drawing in-and-of-itself—and, in the long run, not the “art,” either. Then again, my opinion doesn’t necessarily matter in these regards, I guess.