With an election year upon us, Toronto doesn’t have a lot for which to be thankful. The fact that our neighbourhoods aren’t being divided by armored cars meant to separate loyalists and opponents of the incumbent prime minister, though, as they are presently in Istanbul, is something we can certainly appreciate.

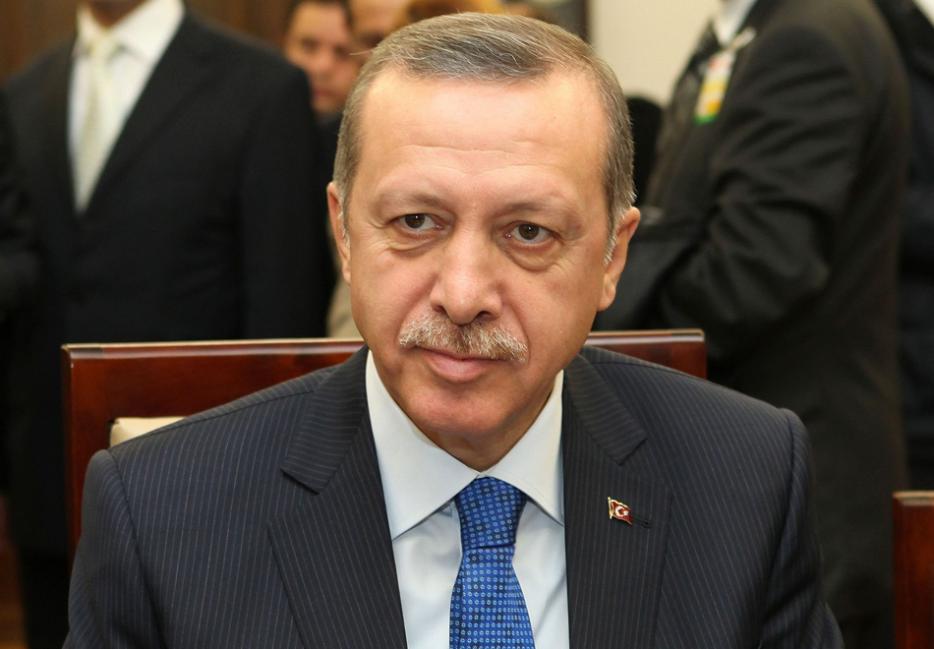

It’s just a visible incarnation of an increasingly divided electorate in Turkey, where this weekend’s local elections will be seen as a proxy for the presidential elections coming in August, and for the future of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP party more broadly. Erdogan rose to national prominence as the mayor of Istanbul 20 years ago, and the AKP has semi-serious worries about losing its political dominance there. The capital Ankara, which has elected an AKP mayor for four terms running, is looking like it could flip to the opposition CHP.

None of this, however, is likely to affect national politics in the near terms. Turkey’s not going to have national parliamentary elections for another year, and municipal elections are strange beasts anywhere, with Turkey being no exception: because of different election rules, the local AKP candidates end up losing to parties who aren’t contenders in national elections. Losing votes at the local level would be a symbolic problem for the AKP, but not necessarily a practical one.

The AKP’s real problems remain the ones it had last year, which have not gone anywhere: an electorate that’s increasingly worried about what Erdogan and the AKP will do when they control the parliament and, after this summer’s polls, the popularly-elected presidency. Last year’s protests in Gezi Park were one manifestation of that dissent, and the past week’s crackdown on Twitter and YouTube hasn’t put anyone’s mind at ease.

But it’s a mark of Turkey’s complexity that even some of Erdogan’s opponents seem to accept the premise that he’s been unfairly besieged by his enemies in what amounts to a judicial coup. Erdogan’s government is being targeted in a corruption investigation where some of the evidence—including tapes from wiretaps—just happened to find its way onto the Internet the week before the local elections (the immediate reason for the YouTube crackdown). And, in the background, there’s always Erdogan’s feud with the Gulenists.

The AKP has thrived as long as it has due largely to Erdogan’s success (especially early in the 2000s) at portraying himself as a moderate Islamist who would clear up the corruption of prior governments without changing the fundamental character of Turkish democracy. It’s allowed his party to cross the divide between the wealthier, more secular cities, and the poorer and more pious parts of the country—or even the poor within the biggest cities. (Straddling that divide is a pretty tricky balancing act: one of the basic issues in the election has turned out to be the AKP’s provision of food and fuel to poor neighbouhoods—blessed relief for its recipients, but seen as vote-buying by the AKPs rivals.)

Assuming the AKP does indeed take a hit in the popular vote this weekend, it may be an emerging sign of something Turkey hasn’t really had much of in the last decade or so: an organized opposition. The AKP steamrolled its opposition in 2002 in the midst of economic and corruption scandals, but now, like so many governments, they’ve been in power long enough to rack up scandals of their own.

If an opposition does indeed show up this weekend, they’ll have five months before they have to defeat Erdogan, should he decide to run in the presidential election. And if that happens, a country whose recent disappointments conflict already with a history of moderate inclinations may have an even more conflicted identity to sort out.