Toronto is growing, but it’s not growing everywhere. According to the 2016 census numbers, released this month, the lion’s share of growth is occurring south of the east-west Bloor-Danforth subway line, and between the city’s two rivers. Meanwhile, parts of the city’s inner suburbs are dealing with sharp population declines as demographics shift and jobs move elsewhere. These are places where the nostrums of Canadian urbanists ring most hollow, where prescriptions like mixed-use-mid-rise (almost always said as a single word) or bike lanes or transit run up against a half-century of planning for cars first, cars last, cars forever.

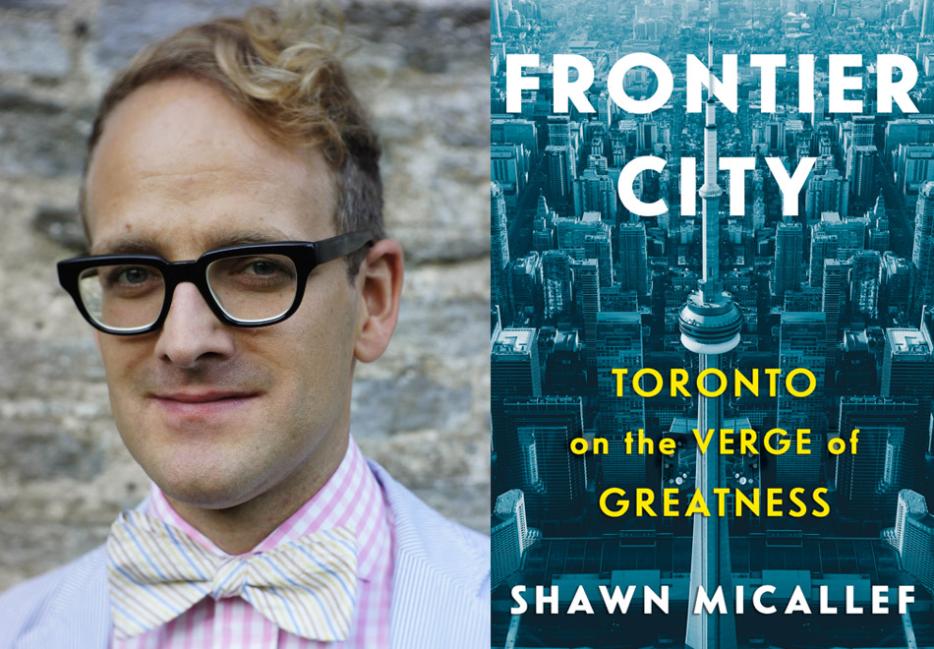

It’s this part of the city that Shawn Micallef explores in his new book, Frontier City: Toronto on the Verge of Greatness. Micallef, one of the city’s ur-urbanists, has nevertheless insisted that his readers spare at least some time to focus on the city’s inner ring suburbs—the onetime cities that joined Old Toronto to create an amalgamated megacity twenty years ago. It’s these places where the story Toronto tells about itself is actually true. As the downtown becomes ever-more stratified along racial and class lines, the suburbs are the places where an actual mixed-income, multicultural city is struggling along.

It’s also this part of the city that produced former mayor Rob Ford, and elevated him to the city’s highest office in 2010. Four years later, many of the wards in the city’s periphery would throw their support to his brother Doug. Not without dissent, though: Micallef walked the streets with candidates challenging incumbent councillors and school trustees across the top half of the city, through lush ravines and packed highways, in parks and parking lots. 2014 was a year in which Toronto was trying to answer what had gone wrong—“a city election is like a civic autopsy”—and Micallef takes us along with the people who tried to answer that question.

*

Hazlitt: This isn’t the first book about our city’s time with Rob Ford—Ed Keenan, Ivor Tossell, Robyn Doolittle, and others have all put out books about and around him. Ford has been gone for a while now, but we’re still digesting what he did while he was here. Where did you start with that job?

Shawn Micallef: The book started at the height of the drama at City Hall, I think June of 2014. It was before he went into rehab, and before the cancer diagnosis. So he was at Peak Rob. It seemed like we needed a book about this. I knew Robyn was doing Crazy Town, the day-to-day drama of Ford was being told. It was history, and I could tell people were going to get tired of it fast. I was trying to figure out, how am I going to cover this? How can I get at this in an interesting way?

Urbanists, city-builders, whatever, people who are plugged in, we knew there were problems. But there was still a sense the city as a whole was moving forward, and yet, and yet … we elected this person. How could Toronto, this urbane city with three universities and shelves and shelves full of reports detailing its problems, how could this analytical think-y city elect Rob Ford?

Also, the geography is so big. How do you go about writing about a city this big? I realized writing this book I don’t understand how mayoral candidacy works in this city, because it’s so big. How do you drill down to the neighbourhood?

The best way, it seemed, was that these interesting candidates kept coming up in my Twitter feed. Candidates from Ward 1 to Ward 44. I found some in other ways, but Twitter was this interesting ear to the ground in the city. And that’s sort of when the lightbulb went on. I asked if I could go on walks with them, and ask them to show me their Toronto. Show me the good stuff, show me the bad, but show me what you’re passionate about.

They’ve got such an intimate reading of their neighbourhoods. They do just endless knocking on doors. I was exhausted just doing these short walks with each of them, but they got up every day for a year and went for these walks.

After the 2010 election, the Globe and Mail ran an article that was kind of a postmortem on George Smitherman’s unsuccessful run, and the last line has always stuck with me: near the end of the campaign an exhausted Smitherman says, “Holy lord, it's big. You think you know the city well, and then you run for mayor.”

Even in wards themselves, the candidates I walked with were generally underdogs and didn’t have big machines behind them. A few helpers and very little money. The way they’d speak about their wards themselves was a bit daunting; 55,000 people is a lot of houses, and every one I walked with said, “I’m not going to be able to reach every one.” The downtown wards you can walk across in fifteen minutes if you’re a fast walker. The suburban wards, those would be hour-long walks or more. That kind of geographic separation doesn’t really come across on the map. There’s challenges to democracy at the ground that are different than in downtown. Even simple proximity within the city.

You walked with a number of underdog candidates. Every one of them, at least the ones running for council seats, lost their campaigns against sometimes pretty unpopular incumbents. You’ve written for years now about Toronto’s suburbs not getting the attention they need from City Hall, but when you look at the election results there’s a lot of complacency. How do you square that?

You could come down and lecture, whatever, condemn low voter turnout. But even in the engaged wards it’s pretty low turnout. It’s just gradients of low. When you’re in Ward 44, Ward 2, the CN Tower is this little stick, this little pencil, a toothpick. That’s where the power is, but when you’re that physically removed from the power it seems natural that the general tendency to ignore municipal politics would be increased.

When you’re down here, you see City Hall more. You’re also closer to the drama of politics. If there are strikes, marches, protests, there’s a sense of politics down here. When you think about the civic political dramas—and there are not really that many—you really see it downtown. In the suburbs it’s tucked away in halls, private and hidden.

In chapter after chapter though, you show places where there’s either a feeling of resentment over City Hall’s priorities, or more commonly just a pronounced sense of absence. The absence of attention, parks left unmaintained, potholes that don’t get fixed, streetlights that don’t light up. The absence of civic attention is keenly felt, but these places keep electing the people who are disappointing them. That’s one of the paradoxes in your book I’m wrestling with.

I hope I didn’t let people off the hook completely. People do have to take some responsibility for who they vote for. But the chapter on [Ward 7 councillor Giorgio] Mammoliti was interesting to me, reading other people’s work, especially Daniel Dale—who [Ward 7 challenger] Keegan [Henry-Mathieu] and I walked with. Why do people vote for this guy, who was the original Rob Ford? [Mammoliti] has been Rob Ford for twenty years in the area. It’s kind of incredible, the power of retail politics. All it takes is someone doing something good for you, fixing a sign at the end of the street, fixing a pothole, and suddenly they’ve done something good. City politics so often feels at arm’s length—it doesn’t affect you personally until it does.

Maybe that’s why garbage strikes are so powerful. It affects everybody, and it builds up. Everyone smells the stink, that’s why it’s so toxic literally and politically, because it touches everyone. In Mammoliti’s ward, people could see their park falling apart and they couldn’t get into it, but if he did something good for them that emotional connection was made. I think I was naive about how much of a role emotion plays in local politics, and politics in general. Telling someone they matter was something Rob Ford was really good at, whether he meant it or not. That connection is political gold, if you can do it.

The Mammoliti example is worth sticking with. In Ward 7, the city had closed a park to car access because of complaints about late parties and messes left behind. It’s a suburban example, but in this city, it could have been anywhere. Like, if people want to stay in your park late with their friends, that’s a sign of success.

People are terrible and they’re messy, and when you’ve got a lot of them in the same place, a city, they’re going to leave a mess.

But there’s nothing about that choice, to close the park to car traffic, that’s really urban or suburban—it’s just Toronto’s particular narrowness coming through. You could find analogs in downtown.

It manifests differently downtown, that urge to not do what it takes to make the thing run.

We seem to be unable to accept the balance of having people live in and use the city.

The theme I discovered [was], in different ways, of Toronto not accepting that it’s a big city. We’re going to have parks that people play in, there’s going to be kids there, there’s going to be noise on main streets at night. There’s going to be nightclubs. There’s a legitimate debate to be had about how many clubs and how noisy, but there’s a knee-jerk rejection of urbanity that’s a downtown thing and a suburban thing.

Today, you pointed out the Toronto Star’s coverage of the Matador, a music club that has been closed for ten years and counting and may never re-open, despite Toronto’s claim to being a “music city.” It’s a mental landmark for me because when I first moved to Toronto in 1992 I lived just a block away, in a neighbourhood that was struggling through the recession.

You should have bought a house.

I was eleven.

I guess.

But it’s this amazing example of how we can’t overcome the roadblocks we put up ourselves.

It’s such a perfect Toronto story, where we’ve got this plan with the support of everyone from the mayor on down, and [it’s undermined] immediately and nobody can seem to fix it.

You’re telling the story of Toronto as it is, not the story Toronto tells itself. The downtown is not, in fact, the beating heart of multiculturalism in Toronto. If we want to talk about middle-class mixed-race neighbourhoods, your stories don’t go south of Eglinton. But you’ve been telling this story for years now. Were you surprised by Rob Ford?

Absolutely. Totally. That’s why I went back and opened the book with the visit to FordFest in 2010. At the time I was surprised, but in retrospect I was surprised that I was surprised. I should have known better. I’m a bit embarassed that I also thought Rob Ford was also a joke. But that was hopeful, too, right? This joker from the edge of town that says funny and dumb things. Seeing all those people there, a mix of Toronto, was an early eye-opening, and that’s how I got hooked into following it passionately.

Outside of the book, a couple times I’ve gone to give guest talks at University of Toronto’s Scarborough Campus, which in my head is just “the other part of U of T,” right? But when I go there, for many students there the centre of gravity in Toronto isn’t downtown—their centre is located somewhere out there, maybe not at UTSC, but their daily life is in a different place.

I was from the suburbs but I was always in love with downtowns; I believe in downtowns because they’re downtown—Petula Clark singing her song—there’s a reason downtowns are where the action is. But not everyone shares it.

That view from the suburbs has a sinister side, though. You mention the G20 summit in 2010 in your book, but aside from the obvious stain of mass arrests I remember Rob Ford and other suburban councillors dismissing the police misconduct by wondering what people were doing downtown on a weekend, as if hundreds of thousands of people didn’t live there.

Think about how people talk about neighbourhoods. They get these reputations—a place is “dangerous” because of a violent five seconds in a year. In the same way that downtown is misunderstood by the suburbs, people downtown misunderstand the suburbs as a barren, boring wasteland.

It’s disheartening that even in a place like Toronto, which is big, but not that big. It’s not a country, it’s not a continent. But even though it’s relatively small those false perceptions of each other can grow. I think a lot of it is wedge politics that’s useful for some people to crank up. I think a lot of it is really imaginary.

On wedge politics: despite the fact that you write sympathetically throughout about Toronto’s suburban wards, nearly every chapter contains some glaring example of racism, or sexism, or homophobia. Those might get amped up for cynical reasons, but there’s an ugly side to all of this, and I’m wondering if the vein of homophobia set your teeth on edge.

It was strange watching it at the 2014 FordFest in Scarborough, watching LGBT protesters get confronted, seeing their signs trampled on. It was almost imaginary, you know? Because that kind of demonstrative homophobia—it tends to be more subtle, I think—it seemed like a movie, which is maybe just the state of watching too much media. It was heartbreaking, because you want the place to be better than that. But maybe there’s some anger about that, and perhaps taking the lid off the illusions of Toronto might have something to do with that.

I don’t want to sound naive, as if there’s no homophobia downtown. But you’re writing about these suburban races and if it had only been one or two councillors—if it had only been Rob Ford it would have been bad enough!—but it comes up again and again and it’s hard to avoid the pattern.

That’s where it happened during all of these events, but there’s plenty of it downtown. I was rammed off the road while riding a bike on Dundas once, by four guys in a car, yelling “faggot.” It happened. I should have included that, maybe, to balance the homophobia throughout the city.

Maybe it’s under the lid more, because the community is so visible from the Village to Queer West. Maybe it’s harder for homophobes to be themselves. Maybe they’re in the closet more because the community is more demonstrative. But if they’d held FordFest downtown I’m certain those things would have come out. FordFest was a kind of politics that enabled that sort of opinion to be spewed, and if the Fords had it at the CNE, or somewhere downtown, it would have happened there. This is where the Fords created the political space for this to happen.

It happened in 2014, not in 2010. Ford had at least as much popular support in 2010, but four years later something about Ford’s time in office had taken the lid off of something we thought had been contained.

The lid was still tightly on in 2010. It was still Toronto The Good keeping it down. It’s just like reading about the rise of Trump, and the increase in racist, homophobic, and anti-semitic attacks since then. You give permission for it to happen. Thinking about this, is that the best state of things? Is that the best we’re going to get, a leader pushing back on hate because the hate is always going to be there? Or is it better to let it unleash and try to solve it honestly? I don’t know. It feels daunting, and it feels like a constant struggle.

I get the impulse to unmask these things, but I have a hard time believing things have gotten better in the U.S. in the last six months, or will in the next four years.

I think that’s why I was so upset about [Toronto Mayor] John Tory being unwilling to cut off [campaign strategist/consultant] Nick Kouvalis. He equivocated on everything. To be a leader, you have to push, you can’t just talk all the time. By leaving the door open, you’re letting it come back in.

You were pretty restrained, all things considered, in the use of Donald Trump in the book given the obvious parallels between him and Rob Ford.

I had a lot more, actually, that we chopped. The revisions were all put to bed at the end of June, and I had a bunch more because I was seeing it happening. But we worried about what if he loses, right? So we tempered it.

While I was writing over the last year there was Brexit happening, then Trump. I’d have the TV or radio on in the background writing about the last four years of Toronto, and the deja vu of that, the U.K. and America, was pretty severe. The analogs were pretty direct: Trump saying he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue; Doug said Rob could kill someone in front of City Hall. So yeah, we had a lot more. But I chose to focus more on Toronto. Also, because the reader can see those things without me.

One of the Americans lamenting Trump said, “from this point forward we will always be the country that elected Donald Trump.” It feels like one of the hopes in 2014 with John Tory, or maybe anyone—that we would just move on as if it never happened. But we’re still the city Rob Ford made us.

Or even just be able to condemn it. But is it actually an animal anyone will have to ride? You can’t just banish it—not ignore it, but beat it back with force? Which I think, rhetorically, condemning Kouvalis and his message would do. It would create a political space where this isn’t allowed. But that door is open now. Is it impossible to close? Or is that just Tory? I hope that’s just Tory.

All of the candidates you followed had more ambitions for city politics than simply keeping taxes low and picking up garbage on time.

I looked for city-builders. I didn’t care what part of the political spectrum they came from. There are some who argue that city-building really can only be left-wing. Jean-Pierre Boutros considers himself a Red Tory. Same with Bryan Kelcey in the David Soknacki camp. I didn’t want it to be left-right, I wanted them to be espousing something bigger, but they were mostly from the left’s side.

But one of the problems city-builders face is that there prescriptions aren’t the solutions suburban voters want. There’s a breach between what progressive politics is offering and what’s being sought.

Part of the problem is the hills progressives choose to die on. I’m as angry as anyone that they removed those bike lanes in Michelle Holland’s ward, because when you go there you see kids riding on the sidewalks. There are bike riders there! But the progressive city-building wins could articulate differently there.

The everyday lived experience of the suburbs, the struggles of traffic, figuring out how to get to the store, maybe that’s a longer-winded way of getting city-building ideas into places where the built form doesn’t lend itself to the same downtown solutions.

But I think this is part of a broader problem for progressives. Look at Trump, who won states where the most people benefited from Obamacare, or parts of the U.K. that benefited most from EU membership voting most heavily for Brexit. The solutions on offer from progressives are often resented.

Yeah, the nostalgia politics. The status quo doesn’t work in these places anymore, there’s just too many people trying to drive everywhere. Nostalgia’s a powerful thing, whether it’s Trump—Make America Great Again, Make Bungalows Great Again. Mel Lastman’s North York, early Etobicoke, these were actually great moments for suburbia. The idea worked for a while, with all of its problems. For a while, it was utopia. The city was there, but you could drive everywhere in your part of it easily.

For so many it’s still living memory. Maybe once it’s no longer something so many people remember as the Good Old Days, maybe that’s when the nostalgia politics won’t have that power. There’s still a lot of baby boomers and we’ve got a lot of good health care, so maybe it’ll be a while yet.

There’s also this weird nostalgia for pre-condo downtown Toronto, which was a sea of parking lots. I think people would be shocked, if you brought them back just to 1998, how sparse the city was even then. It gets back to what we were talking about at the beginning, the resistance to the city-ness of Toronto. The success is the same thing that makes people nervous, that it is a dense place.

Part of the problem is a general resistance to change everywhere, not just in the suburbs, but certainly among some of the councillors elected there.

John Parker, who lost his seat in 2014, is a funny example. He was a Tory in provincial government and he’s joked, I think, that coming to city politics made him a socialist. There’s just something more hands-on about city government that will always need more rules. You can’t have millions of people in one place without rules for them all to get along.

There’s no more regulated place than New York City. There’s no more capitalist, free-market place than New York City. Those two places exist on the same island. I was having this argument on Twitter about parking signage, and someone saying this is “such a Toronto problem.” I complain about Toronto problems all the time, but look at New York! It’s even more regulated, but people here don’t call New York a nanny state. People just accept that a million people on a small island need those rules.

One of the constant things that happened to me during the Ford years, and I’m sure it happened to you, was friends and family basically asking, “Is this really happening?” As if people wanted either to be told it wasn’t, or to be let into some secret about what was happening at City Hall. What’s true for you now that wasn’t before?

One thing that’s true is that the plans I thought were good city-building plans—Transit City, Tower Renewal—might be good, but it’s really hard to communicate that to people that feel—justly or unjustly, truly or un-truly—burnt and cynical about the cynicism. What’s true is the cynicism, about the city and the institutions about it. It’s deep, and it’s a force.

One reason I have hope, one hope I took out of this project, is that the city is so close to the ground, maybe this is the place to remake those connections between civics and constituents and jump over that cynical divide, that’s grown like a hide. Look at the resistance to Trump: it’s happening in cities. Maybe that’s something to be excited about: when times are very dire, these other questions get pushed aside and we rally.