I am grateful for this life! And yet I miss the alternatives. All sketches wish to be real.

—Tomas Tranströmer, The Blue House

The fertility clinic’s waiting room featured photos of chubby, healthy, smiling babies. No photos of women, though. Despite fluorescent lights, the space felt furtive. Other waiting people, also alone, seemed flat-stomached beneath their winter coats and avoided each other’s eyes. It felt embarrassing and painful. Shouldn’t this process be simpler? Some people have children accidentally. Some people struggle to conceive. Some people choose to or need to end pregnancies. And as reproductive rights are demolished and threatened, most of us fear no choices at all.

I visited this clinic to evaluate my body’s fertility. I’d waited years to ask a doctor questions. I hadn’t decided to have a child, but I wanted to know what was possible. Hormones would be tested; images would tell a doctor what state my body was in. Could it be a viable host? Were my eggs even “good”? More bluntly: what if my body made the choice of whether to procreate or not for me? My own ecosystem might block any self-determination. The delicacy around deciding to have children often felt vulnerable to me, ripe for criticism, but if my ability to reproduce was decided for me, by my failing biology, I could perhaps shed some judgement—even my own.

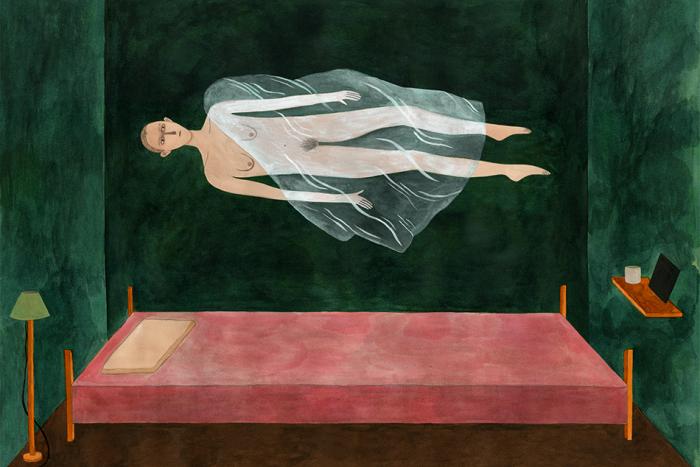

From the seating area, I was called to a dark exam room. I changed into a paper gown, laid back, put my feet into stirrups, and the technician guided a wand inside me, warning that she could not interpret what appeared on the ultrasound screen. The experience would be magical if it weren’t so uncomfortable. Some people come here and see a fetus throbbing. All I saw were abstractions: a dark ball with white streaks I could barely decipher. “These are your follicles. And this,” she continued, pushing the wand toward my left side, “is… a growth. Maybe a fibroid. I can’t see past it. The doctor will have to look at this.” It’s unnerving what operates unnoticed in our bodies.

***

Before this appointment, my health hadn’t been perfect. Years of chronic digestion issues, for one. I dropped weight easily. Experimented with bitter herbs. No bread. No oil. No coffee. Acupuncture and the tiny sugar pellets of homeopathy. Endoscopies. Nothing had helped. No diagnosis, so modern medicine said to live with the mystery.

Obscurity gaslights and overwhelms. Without answers, I felt deep frustration with my body’s unreliability and discomfort. I struggled to describe the way I can operate at a baseline, put on makeup, and play with bursts of energy until I can’t. When pain becomes standard, sometimes you read your body’s changes incorrectly. I’d looked bloated for a few months. Lying in bed, a hard growth strained the skin below my belly button. Because this bulge wasn’t painful, exactly, I assumed it might be another digestive symptom or an uninteresting aesthetic change—age-related, maybe. I’d been sure the fertility appointment would give me some answers. In profile, in front of a mirror, I could’ve been mistaken for slightly pregnant.

***

In November last year, I went to the Sonoran Desert with my mother. She’s easy to be around, generous with her flight points. We don’t get much time alone together. I craved a change of climate, not just to escape the Maritime cold. I felt murky in my relationship with my partner, N, which wasn’t helped by the Haligonian fog and perpetual drizzle. The winter sky is grey, hazy. A Halifax local explained that, since the ecosystem won’t offer it to us, we have to make our own sunshine. Instead, I took several long flights to dry out in the desert sun.

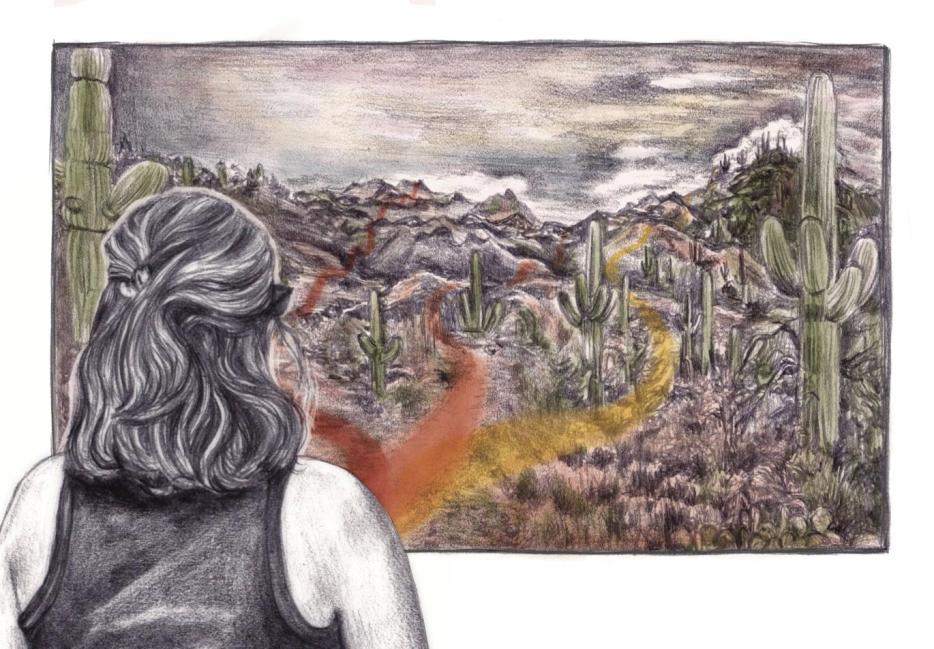

As we drove into Saguaro National Park, the unfamiliar landscape saturated me. My mother liked to drive, so I stared out the window and marvelled. Endless cacti, a forest of them, threw their shadows across the red land. As the road wound around hillsides and mountains, they appeared to pivot. Some were nearly twenty-feet tall.

Sonoran Desert plants appeared indistinguishable to me at first, prickly and peculiar. Ocotillo at regular intervals, palo verde and round barrel cacti, one saguaro cactus then thousands of others, arms akimbo. Some knobby with new growth, some short or gigantic, some suffering or shrunken, some reaching over paths and roads.

I hiked a mountain trail with my mother. We sweated, but our clothes didn’t get damp—the dry air whisked moisture off our skin. I could feel the sun penetrating into my light-starved body. The trail cut through a dry wash, a ditch in the desert that fills with water after rare heavy rainfall and creates a temporary river; the park information centre called them xeroriparian and “chronically disturbed” habitats. Washes become specific plant ecosystems, sometimes filling with bright wildflowers or nurturing trees and shrubs along their perimeters.

I texted with N in bursts of tension. We’d moved in together recently, and every other week were joined by his two teenagers; those intervals were fun and crowded and overwhelming. He’d had years to learn how to live with children, but I was fresh. I absorbed much of the environmental friction that adolescents bring. Others’ needs made it tough for N and I to connect. Together, we entered some circular logic: I felt unappreciated by him, he felt hurt by my portrayal, and so both of us would drift toward despair. These conflicts pulled me into speculation around parenthood; I couldn’t find my own desire or lack thereof, and didn’t know whether my ruminations would ever evolve into clarity, or clarity into action. Is there anything more painful than being uncertain?

***

From the initial ultrasound, the doctor couldn’t see enough detail, so he ordered an MRI. Fibroids are benign, I reminded myself. Benign. When the MRI date came, I was sent to the women and children’s hospital, deposited into a waiting room with a replica MRI machine painted to look like a spaceship. Changerooms were “pods,” and astronauts and planets decorated the walls. The kind staff gave me earplugs and headphones and offered to play music. Looking at the bizarre environment, I requested Björk. They asked me, again, how claustrophobic I was. Armed with a panic button, I was rolled inside. The tube was louder than I imagined, like the deep earth jackhammering of apartment building construction. I could barely hear Björk wailing over the noise.

Now, in my late thirties, the majority of my peers have turned into parents. My relatively privileged social circle now holds children and the frantic changes raising them requires. Unlike me, the parents aren’t lost in speculation. Their thoughts are crowded out by needs. I listen to their stories and they feed my apprehensions. Rollicking home births, c-sections, traumatic hospital events, in-vitro budgets, ovulation apps, nine-month nausea, antidepressants, and sleeping pills.

One friend wrote to me recently having realized, after moving to a new city, that people only knew her as a mother; she misses people knowing her when she was just herself, young and stupid. Friends of mine have been confronted with carelessness, from terminology like "geriatric pregnancy" to "mother," which do not fit their identities, to judgement about how they perform as a pregnant person.

My best friend tells me—while pregnant with her second baby, parenting a toddler, and working full time— about a colleague who commented on her pregnant belly, that it seemed outsized for how far along she was. Another colleague scolded her for admitting she enjoys an occasional glass of wine. Her struggles with postpartum depression had been often dismissed by others as “the blues,” their reactions tinged with skepticism, with shame.

I’ve known pregnant people who were reprimanded for riding a bike, for sitting at a bar patio, for considering anxiety medication, for announcing too soon, for exercising, for working, for going on maternity leave “early.” Uninvited opinions careen toward the bump. Some judgement must penetrate. As a person without children, I’ve been encouraged to have them by strangers and extended family (“just do it”), the subtext being disapproval that I haven’t already done so.

One dear friend has always known she desires no children and her partner feels the same. I admire their sharp decisiveness, embracing their designed lives.

No one I’m close with has decided to embark on pregnancy and child-rearing alone.

When it comes to fertility, researchers find decision-making to be an interactive process, highly influenced by the people around you. It’s both decisions and biological events. Daniele Vignoli et al write that society’s institutional configuration—what supportive or oppressive structures encourage or impede someone’s fertility decisions—alongside someone’s background—like associations with parenting and family, and their socioeconomic status—set constraints. Our perceptions about these factors influence our decision-making.

***

The day-to-day struggles with N’s teenaged children include screen-time habits, chores, and moody conflicts. Most of his friends, around a decade older than me, have split families and they all have children. The stereotypical family scaffolding is in place. I’ve stepped into a version of a family planned by two people whose vision has, mostly, fractured. It’s like wearing an outfit which is beautiful, but not what you’d choose for yourself. I suspect that many people in such situations become experts at accommodating, following another’s guidelines. I wonder if being adaptable makes other options, different configurations of family, more obscure and elusive.

I’ve asked about N and his ex’s fertility decision making, and it singes my ego. It happened quickly: they both wanted children young, they were in love and excited. How breezy it sounds, how secure. And more than that, how romantic to know another person agrees to be connected to you forever. Things didn’t work out, but they’ve shared one of life’s Big Experiences.

Making decisions has felt tricky to me for a long time. I feel trapped, I get lost in thoughts. I’m surrounded by sensitive, wonderful friends who listen carefully and do not push. Sometimes I wish they would. What harm would I cause by not having a child? Probably none, but I’m not sure how to prepare for regret, or whatever opaque wonderings might emerge. Would they morph into resentment?

***

Saguaro cacti are unique individuals, but to my untrained eye they were too similar to allow me to situate myself. They were playing tricks. Who have I passed by? Was this the same split in the trail? Was that bottom arm pointing down or up? How many trailheads were there? Turns out there were many.

From the viewpoint of this trail, we saw Mexico in the distance. As we trudged around, I asked my mother how she decided to have children. I just always knew I wanted them, she said between taking photos of cacti. My mom had good associations; she grew up with a sweet mother and six siblings for company. I asked her how she got through the stress of parenting, the lack of sleep and being swallowed up by my baby needs. You just get through it, she said. The simplicity of these responses fed my anxiety; I checked for intuition but couldn’t locate it. She told me something like, when you have a baby, you love them so much you forget the hard stuff. A few years ago, she asked me if I ever wanted to have children; she cried a little, explaining that she wished for me to be happy, but what I saw was pity. I was in the throes of an abusive relationship at that time, and the concept of a child, of a future, seemed many realities away. Now, I thought, she’s happy I have a good partner, though surprised by the teens in my life; she listens to my indecision and follows whatever direction I’m leaning. In subtle ways, I sense she wants me to find happiness the same way she did, with a nuclear family, with my own children.

The mapped trail was a loop, so as we came down a small mountain, growing more tired, we followed a trailhead sign. But this route brought us to an unfamiliar parking lot. Where we wanted to go must just be down the road, I suggested. The sun was mid-day blazing and we’d been out for a few hours. Though I hated to admit it to myself, we were lost. Mom’s face looked bright red. We’d run out of water, which was my fault, and our phones weren’t working. So I made her wait under the shadow of a covered picnic table and jogged out to the road. I ran about a kilometre in one direction and back, then returned into the trail toward our last wrong turn, backtracked, and brought Mom with me. I thought I’d recognized a way out; second-guessing had gotten me even more confused. Another click or two in, I recognized one particular saguaro—dead and blackened by a lightning strike, with its woody ribs remaining—and we made our way out.

***

I’ve never made a choice I couldn’t take back. Unlimited options can feel like drowning. And yet, the concrete blockage of one path felt equally impossible. How can anyone be sure? Friends who are parents, and my own mother, just knew, as some intuitive, cosmic force, that they wanted children. Their bodies and brains fell into sync. They operated with freedom to consider, and nearly all had partners along for the experiment; not all the partners stayed. One friend says she craved the chaos of children to distract her from neurotic introspection. Another remembers her lonely childhood with a single mother and resolved it with a partner from a large family and three children. One never felt any connection to children, plus, they said: climate change. One intended to de-gender their parental labour. One had one child, then had an abortion. One more had an unplanned pregnancy and said they don’t regret it, but given the choice again, would not have had children.

Before I met N, I imagined children. I speculated about how much I liked them. I enjoyed infants, and children six years old and up, but the ages in between seemed both overwhelming and boring.

I felt maturity’s creep. I considered raising a child alone—I admired fierce solo parents. But I couldn’t grasp how someone decides to explode their life, even if they do so with love. When does ambivalence feel like an answer?

Still, I wanted to ask the questions. When I moved to Nova Scotia in 2021, I got on the clinic’s list and was contacted three years later. My circumstances had shifted drastically, my body had aged, but I remained curious. I wondered if I’d ever have a job that could support parenting. I wanted to examine a part of myself representing a road I might not go down.

I detailed my appointments to a friend, a mother and artist experiencing her own health crisis, who reassured me. Art’s generative and nurturing capacity is always available. It does not depend on our biology or status. I can keep going in any direction, or I can stay lost. She showed me a picture of Georgia O’Keefe’s studio. Antlers flank a slate-like fireplace. A bowl of bones and shells was notably out of place in the arid southwest. Their spirals. Jars of earthy pigment. How she made everything from the environment. It speaks to the overlooked richness of the desert.

***

When I talked to N about my initial fertility appointment, about investigating my body, potentially putting some eggs on ice, he seemed betrayed. And in a way, he was. I’d begun to construct a future without him. I regarded this fertility inquest as a kind of plan B. What if we break up and I no longer have children in my life? Maybe I’d spring into action. In our relationship, we’d barely discussed my interest in having children, in part because he already has two, and also because I’d always answered that I was unsure. There were constraints, hard-to-imagine futures. Nothing had aligned to make me have children. If I really wanted them, wouldn’t I have them by now?

During my undergrad, I went on a date with someone older who withheld that they had a child. I saw them on Bloor Street, holding hands with a toddler, caught off guard. Next time I saw them, they apologized; they explained that their ex-partner had really wanted a child. Her biological clock, they offered. I shrugged this off skeptically, pretentiously, and asked if it wasn’t just societal pressure. It seems pretty real, they had said. I’d only understand this exchange a decade later.

***

Unlike Nova Scotia’s typical atmosphere, the sky in Arizona is not hazy or dim while I’m visiting. From all over Saguaro National Park, the view is expansive and clear. I’m not sure why the desert has barrenness built into its mythology. So much grows, all plants with extreme resilience. The desert resists being manicured.

My mother and I wandered through visitors’ centres, marvelled at lizards and birds I’d never seen before. We ate nopales and barrel cactus fruits that tasted like bell peppers. We couldn’t drink enough water. And we stared at saguaros everywhere. The saguaro’s shallow roots spread out as wide as the plant is tall, remaining close to the surface to absorb more water during a rainfall. One saguaro we saw must’ve risen thirty feet. It was probably 200 years old. Saguaros are federally protected, so people often build structures around cacti.

Over the last twenty years, saguaros have not been re-establishing their populations in the wild. They require very specific environmental conditions—a strong monsoon season with plenty of rain, a winter that doesn’t surge in temperature, a summer that doesn’t scorch new, young plants—but as climate change disrupts any predictable weather patterns, the cacti suffer.

I read about a conservation group, the Tucson Audubon Society, that is removing an invasive grass species that has fueled wildfires across the Sonoran Desert. The volunteers are planting thousands of young saguaro cacti to replenish their population. Even the saguaro, evolved to survive harshness, requires interventions.

***

Not too long after my MRI, the results were uploaded to an online portal. Most of what I could decipher were measurements; the growth was bigger than my uterus. The pressure and fullness and tenderness, the strained zippers of my jeans, the tiredness I’d been experiencing, all came into focus. Fibroids are under researched, like most women’s health issues. Globally, “uterine fibroids are among the most significant diseases of reproductive-age women,” according to one paper published in Reproductive Sciences, but treatment options remain extremely limited. Eventually, the fertility doctor followed up. It was a large fibroid, he confirmed with a shrug, and I would need to decide how to deal with it. If I don’t want to have children, it would be easiest to just have a hysterectomy. No more uterus. He was markedly blunt in his approach.

If I do want children, the fibroid would impede a pregnancy by crowding a fetus or bursting. I could get on a list to have surgery to remove the fibroid, recover, then try IVF, but my bloodwork revealed diminished ovarian reserve. Save up or go into debt for several thousand dollars to try for a few embryos, one of which may or may not be viable. I briefly imagined going through the procedures on my own, hormonal and still uncertain. I was told to think things over. The phrase “time isn’t on your side” was deployed at least twice during this appointment.

I was referred to another gynecologist and met with her several months later. Medical wait times were not factored into my limited window. At the appointment, a resident sat down with me first. “So, you want to have surgery?” she asked, almost accusingly. No, I explained, I have a giant uterine fibroid and I’d like to know what’s to be done about it. Once the gynecologist came in, we discussed options, which included expensive hormone injections and potential early menopause, invasive surgery, less invasive surgery, possible hemorrhaging, removing the uterus entirely, or living with the growth until it becomes really, truly unbearable. A surgery date was unpredictably far into the future. The two of them prodded my abdomen, felt the fibroid; they told me that by measurements, I’d be sixteen weeks pregnant. It would keep growing. More decisions, more overwhelm. No matter which surgery, if I ever became pregnant, I wouldn’t be able to labour naturally—my uterus could rupture. For some reason, this fact sank me.

“Unfortunately [we] live in a pronatalist world,” the therapist and “parental clarity mentor” Ann Davidman writes in Vox, and ambivalence around this topic is not offered much space. She describes how many people focus on fear and pressures from societal or family messaging; they decide to allay that fear, rather than to embrace a desire. Davidman references people who didn’t want to be parents but end up enjoying it, and those who want children but enjoy their full, child-free lives. But, she says, “chance is not the path to a fulfilled life.” One’s desire and one’s decision may not line up.

Or, in my case, indecision ends up being its own decision.

In a study that interviewed women who chose solo motherhood, the decision to parent alone was preceded by “a long process of reorganizing ideas about family.” Often, women had hoped for an idealized nuclear family but lost this “dream,” and worked on detailed plans and achieving “socio-emotional acceptance” for solo parenting.

To make a life, once decided, how much needs to align perfectly? One’s ecosystem—biology, circumstances—needs to be in sync. My desire is to have my decisions go uncontested, to be safe and empowered in these choices. Shame lingers in that place of indecision. If I were younger, healthier, richer, had stronger urges that shaped the future, many options could present themselves. But instead, I’m navigating limitations and biology.

I’ve merged into an existing family. I try to articulate to my partner that occasionally this role I signed on for feels extraneous. I look at all the moving parts that make a family; closeness, trust, and presence. It isn’t what I expected it to look like. I have, in melodramatic terms, no blood ties. I could be snipped away at any time and relegated to memory. Like any kind person would, N reassures me this isn’t true. Deep down, I’d rather be indispensable. One has the flexibility to make more mistakes as a biological parent. I have to negotiate at every step. A lot of moments seem to carry too much weight inside them. They linger too long, treading water.

***

In the desert, the winter sun was still powerful enough to burn me. I was intrigued by the parts I missed with suncream. A gap between bra straps, a finger’s width of white streak on my chest, pink on my ear’s upper curve.

Saguaros grow incredibly slowly. A ten-year-old plant may only be one and a half inches tall. Cactus arms only begin to appear when the saguaro is around fifty to seventy years old. The miles and miles of cacti I saw were ancient. Their existence seems miraculous. They can only grow with the help of “nurse plants,” often mesquite, palo verde, or ironwood, that protect them from environmental extremities. For years, these parental plants offer cool, moist microhabitats to nurture the vulnerable saguaro seedlings. As they become larger, saguaros often compete with their nurses for nutrients, or crowd them out.

The morning after we got lost on our hike, I woke up around dawn, the time change still shifting in my mind. Outside, I stared into the unfamiliar reddish landscape, and caught a flash of movement. A coyote trotted by, regarded me, and blurred into the land. It seemed to disappear. It could have gone in any direction. A moment of surprising life, and me, brooding about the future. My body ached a little. I thought about how expectations ruin experiences. The sunlight started to illuminate the cacti. How many of them persist. They keep growing and reaching. I wrote to N that I missed him and sent an image of the sunburns on my skin, the unusual patterns.