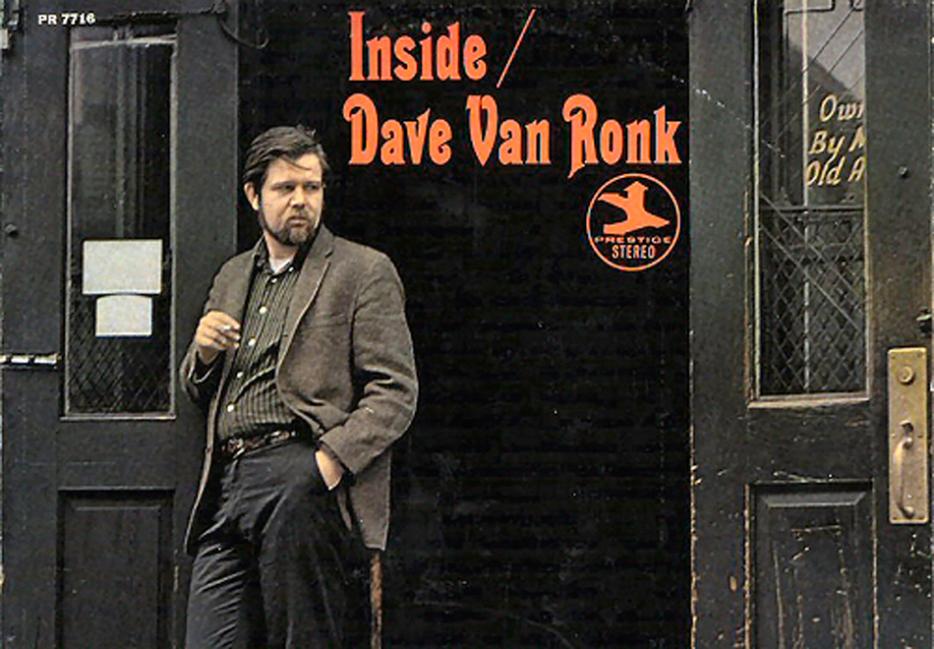

If you know of the musician Dave Van Ronk, you probably love folk music more than the average person. In his four-decade-long career, he wrote exactly one hit—“Bamboo,” recorded by Peter, Paul, and Mary—as well as an iconic version of “House of the Rising Sun,” which was plagiarized by Bob Dylan and popularized by the Animals. Though he recorded more than 20 albums, most are relatively unknown; a few are minor classics among people with old-timey sensibilities. Today, Van Ronk’s biggest claim to fame is having inspired the Coen brothers’ new move, Inside Llewyn Davis.

With Llewyn Davis, the brothers revisit the New York folk music revival of the early ’60s. The film is a character study, but also a portrait of a community and a moment in time, and while Van Ronk is hardly the most famous musician of the era, he’s the perfect subject for the film. In the bars and coffeehouses of Greenwich Village, he was something like a mentor, a maharishi, and a consigliore. If you needed a couch to crash on, Dave was your man. If you wanted 15 minutes of stage time at one of the dingy basement venues where folk musicians played, he’d introduce you to the right people. (Van Ronk helped Dylan get a regular gig at the Gaslight, a former coal cellar that became the beating heart of the coffeehouse scene.) If you loved Van Ronk he would love you back, and if you pissed him off he’d unleash a torrent of rage. (He may have had a Dutch name, but as his temperament and drinking habits suggest, he was more Irish than not.)

Van Ronk was the ultimate scenester, and his life story captures all that is wonderful and limiting about being a big star in a small constellation. In the village, you’d be judged not by looks or business acumen or social connections, but by your knowledge of sea shanties and Appalachian fiddle tunes. People shared what meager resources they had, so you didn’t have to be employed to survive. Everybody had a nickname (Van Ronk was known as the Mayor of MacDougal Street), and many had made-up origin stories (Dylan claimed to have rode into town on a boxcar).

This romanticism might seem cloying, but it stemmed from a real sense among left-wing musicians that they had been entrusted with an imperiled tradition. Vernacular American music had deep connections to labour unrest, agrarian revolt, civil rights, and abolitionism, and the threats to its survival were real: many older folksters had personally experienced the financial and psychological devastation that came from being blacklisted. But while unconventional in most respects, the community held conservative aesthetic values. For your music to pass muster with Van Ronk and his purist set, it had to be authentic—which is to say, it had to sound passably similar to the southern blues or slave spirituals or hillbilly ballads that you were imitating. Nostalgia wasn’t just a sentiment but an ethic, and Van Ronk was its chief enforcer.