One of the few traces left of Al Goldstein in New York City is in the Cortlandt Alley in Chinatown, in a doorway that houses New York’s smallest museum, called Museum. Next to rotating exhibitions like tip jars from around the world and various kinds of fake vomit are several shelves of “Personal Ephemera of Al Goldstein,” selected from what remains in the Great Pornographer’s storage locker.

There is a bound volume of Screw, his long-running magazine, opened to a black-and-white picture of a pendulous breast. There are three electric razors—Goldstein had at least ten, plus almost as many coffee makers. There is a letter from Mel Brooks declining to testify at his obscenity trail, and pages of Dictaphone transcriptions, and a cab driver’s license that Goldstein always renewed in case he lost his fortune. He never drove a cab again, although, between 2002 and 2004, he did lose his fortune: the midtown penthouse, the California apartment, and the Florida estate with a statue of a middle finger that greeted passing boaters. The storage locker was all he had in the world.

When Al Goldstein accepted a lifetime achievement award at the Adult Video News Awards in 1998, David Foster Wallace wrote of Goldstein’s “Yeah-OK-I’m-Scum-But-Underneath-All-Your-Hypocrisy-So-Are-You-and-at-Least-I-Have-the-Guts-to-Admit-It-and-Have-a-Good-Time persona.” Foul-mouthed, proudly sophomoric, and weighing over 350 pounds at his peak, Goldstein gleefully embodied the platonic ideal of a “fat, Jewish pornographer.” So thoroughly did he embody this persona (“I want to thank my mother, who spread her legs and made all this possible,” he told the audience) that, Wallace observed, he was “hard not to sort of almost actually like.”

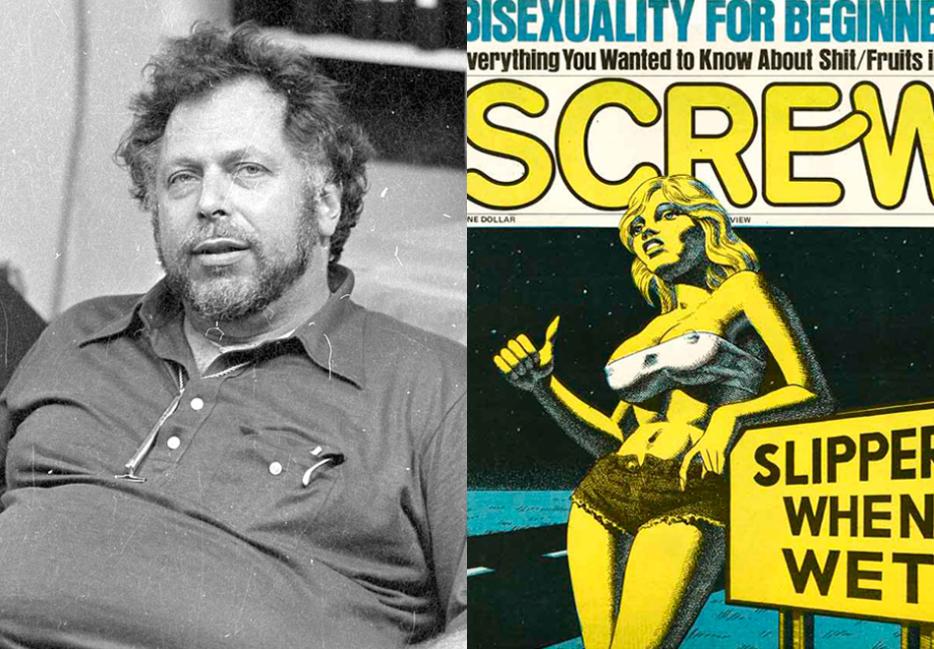

Goldstein launched Screw, his “weekly sex review” of New York, in 1968. United States courts were regularly redefining what constituted obscenity and what passed for “redeeming social value,” but from the beginning, Goldstein said, “a hard-on is its own redeeming social value.” Unlike Playboy, the publication to which Screw stood in contrast, there was no attempt to flatter the reader’s sense of sophistication, or to depict sex as anything but a physical act. “The word love is alien to us,” said Goldstein in his 1974 Playboy interview. “Who needs love? Yuck! We deal with masturbation, the most common sex activity for most people, in graphic words and pictures.”

“Fantasy runs rampant over reality in the world of sex—witness Playboy and the sexploitation tabloids,” wrote Goldstein. “We will apologize for nothing. In the ear, or up the nostril—it’s your bag and your own business.”

Six years after the Adult Video News Awards, Al Goldstein was homeless, after a fortune once estimated at $11 million had been swallowed by divorces, lawsuits, and the changing porn industry. At the time of his death on December 19, he lived in poverty in a nursing home in Queens. While contemporaries like Hugh Hefner and Larry Flynt still live comfortably off their brands, hardly anybody remembered Al Goldstein.

*

Alvin Goldstein lost his virginity at age 16 to his uncle’s girlfriend, in a tryst arranged by his uncle. It was a rare bright spot in the young man’s adolescence. Born in 1936, Goldstein grew up in a Jewish neighbourhood in Williamsburg where he struggled at school and was regularly bullied by classmates. Awkward, overweight, and with a stutter that lasted until age 12, Goldstein found solace in pornography, particularly the “Tijuana Bibles” (comic books depicting famous actors and characters going at it), of which he had an unrivaled collection. His early interest in erotic literature also led him to such pioneers of ugly, explicit sexuality as Henry Miller and Allen Ginsberg, who he later interviewed for the Pace College newspaper.

Goldstein’s sexual education continued at age 17, when he dropped out of school to join the Signal Corps as a photographer. He regularly sought the services of prostitutes, contracting the clap from one of them at age 20. After an honourable discharge in 1958, he enrolled at Pace, where for the first time “he did not feel socially and intellectually inferior to nearly everyone around him,” wrote Gay Talese in his study of the sexual revolution, Thy Neighbor’s Wife (1980). It was also the first time “that he did not automatically expect to pay money for sex.”

But the years following Goldstein’s short-lived stint at college were marked by a string of personal, professional, and sexual embarrassments. A first marriage ended when Goldstein’s wife left without a trace and ran up his credit cards. He struggled in the aftermath, working variously as an encyclopedia salesman, taxi driver, industrial spy, midway carny, and tabloid writer, pumping out freelance articles and salacious headlines. His love life was a disaster: of the dozens of women he approached for dates through correspondence clubs and personal ads, only two responded, both of them prostitutes. During and especially after his first marriage, Goldstein sought refuge in brothels, stag films, and massage parlors.

His course changed when, at 32, he met Jim Buckley, a 24-year-old typesetter at the New York Free Press who edited one of Goldstein’s articles. Tired of his job, Buckley told Goldstein he wanted to start his own publication; Goldstein liked the idea of a pro-sex rag. They pooled their assets (some $300), with Buckley doing typesetting and Goldstein writing content, and on November 29, 1968, their filthy baby sat on 24 newsstands.

The first issue opens with “What We Stand For,” a Goldstein-penned declaration of principles. Screw, “the most exciting new publication in the history of the world,” would be a Consumer Reports for sex, grading stag films, vibrators, peep shows, massage parlors, and other areas of pleasure that went unacknowledged in polite society. It would not condemn any kind of sexual activity, nor would it pander to fantasy. “Fantasy runs rampant over reality in the world of sex—witness Playboy and the sexploitation tabloids,” wrote Goldstein. “We will apologize for nothing. In the ear, or up the nostril—it’s your bag and your own business.”

In Screw’s third issue (January 24, 1969), one “Maxwell Twiford Hollander, Ph.D” (guess who?) expanded on this point with an article called “Can Playboy Get It Up?” “The Playboy world is peopled with hairless women and cockless men,” explains the good doctor. “A Catholic world that Cardinal Spellman would have felt most comfortable in. A world like Camelot that doesn’t exist on anyone’s map. Yet, filled with girls who are not ugly and men who are all winners; This is the infantile adult’s world of childlike fairy tales. Ugliness and flab, drooping tits and premature ejaculating men are not its inhabitants.”

Where Playboy published gauzy, airbrushed pictorials, Screw had hardcore, gynecological spreads. Playboy boasted nude pictorials of Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and the early Bond girls; Screw’s biggest coup was grainy nude snapshots of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis taken with an extra-long lens.

The doc continues, “It is a world of hypocracy (sic), sham and deceit. Apparently, six million readers of the magazine can’t be wrong and so they only manage to get through each real day filled with failure and dissapointment (sic) by mainlining the false promises supplied by old Heffner (sic) and a host of self-serving advertisers who relax the readers’ fears by the simple stroke of the consumer purchasing whatever product is extolled and that will banish self-hate, insecurity, inadequacy and virginity at age 36.”

“Erotica” was not part of Screw’s aesthetic. Where Playboy published gauzy, airbrushed pictorials, Screw had hardcore, gynecological spreads. Playboy boasted nude pictorials of Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and the early Bond girls; Screw’s biggest coup was grainy nude snapshots of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis taken with an extra-long lens. (This issue, headlined “Jackie Kennedy Naked,” sold 530,000 copies over two printings, even though no mainstream outlet would accept Screw’s advertising).

Playboy had its bunnies. Screw had Jody Maxwell, dubbed “the Singing Cocksucker” by Goldstein for her ability to enunciate “How Much is That Doggy In the Window?” during the act; and Honeysuckle Divine, a Times Square stripper who could shoot objects from her orifices (“I thought that was unbelievably disgusting, so naturally, we made her our symbol,” said Goldstein). Both demonstrated their talents in SOS: Screw on the Screen (1975), a stridently unsexy attempt at a cinematic newsmagazine that included a lot of goofy comedy, a gay scene, and several minutes of Goldstein ranting about America’s sexual hypocrisy.

“We make no effort to be artistic,” Goldstein told Playboy in 1974, after Screw had made him wealthy. “Our photographs are so explicit the readers can see the come running from a girl’s mouth. Our stock in trade is raw, flailing sex.”

“The most important factor of all is that we know our kinky audience—those who’ve been overlooked by other publications. If we had the money to conduct a comprehensive survey, I’m sure we’d find a preponderance of foot fetishists, ass fuckers, pederasts, onanists, sadomasochists and all the rest of the denizens of the sexual twilight zone. These are people I sympathize with, because they’re just as horny as I am.”

Playboy had the debonair, sophisticated WASP Hefner; Screw had the obese, crass, and very ethnic Goldstein. Hefner often shot the early Playboy pictorials himself, leaving articles of his clothing in the background to hint that he’d seduced the women; Goldstein admitted (or perhaps bragged) that he could rarely get laid unless he paid for it. Hefner lived a lifestyle that his magazine urged readers to strive for; Goldstein was proudly in the muck with the rest of us. Screw gained enough counterculture credibility in the late ’60s and early ’70s to score interviews with Henry Miller, Salvador Dali, and John and Yoko (during their Montreal bed-in), but Goldstein was the kind of interviewer who could bring anyone down to his level. He got Jack Nicholson to admit he used the magazine to masturbate.

And Goldstein was not merely a chronicler of the porn industry: as the first journalist to seriously review porn films, he shaped it. Had Goldstein not written a rave review of a low-budget film called Deep Throat (“I was never so moved by any theatrical performance since stuttering through my own bar mitzvah”), it would never have become a hit at New York’s World Theater, would never have been targeted by the vice squad, would never have spawned a First Amendment cause célèbre, and might not have led to the modern porn industry.

*

Manhattan public access was conceived as a community forum, open to the public on a first-come, first-served basis, but its free speech mandate allowed for unusually lenient policies on nudity and profanity. So, like most utopian concepts, it was quickly co-opted by people like Al Goldstein. In 1974, New York night owls witnessed Goldstein’s foray into television, a black and white talk show called Screw Magazine of the Air, launched under the guidance of Screw editor Bruce Davis and, soon, leftist journalist Alex Bennett.

“I met Bruce at the bank one day,” says Bennett. “I said, ‘You know what’s wrong with that program? You do it live.’ I said, ‘You should really just take cameras out and shoot stuff on the outside and make it like a newsmagazine and let people see what’s going on in the sexual world, rather than just bring in people to talk about it.’ He said, ‘Well, we don’t have the equipment.’ I said, ‘Well, I do—I have a camera, I have a deck, I have an editing machine, and we can do it.’” After 13 episodes, Bennett renamed the show Midnight Blue—partly because a public access show could not be named after a commercial entity, and partly to establish its identity apart from Screw and Goldstein.

If Goldstein has anything in common with Hefner, it’s that they both embodied wish-fulfillment fantasies—Hefner with his Playboy lifestyle, and Goldstein with his gleeful, unashamed loathsomeness. It might not be possible to defend Goldstein’s vile rants, but something about them appeals to our pure, selfish id.

No television show has done a better job documenting the sexual underbelly of a specific time and place. In its early years, Midnight Blue captured porn star Georgina Spelvin doing her nude tap-dance act at the Melody Burlesque; Tara Alexander attempting the world’s biggest gang bang at Plato’s Retreat, the New York swing club; the 10th anniversary Screw party, where Buck Henry and Melvin Van Peebles hobnob with Goldstein’s jurors; and an early look at the S&M community in New York. Throughout its run, Midnight Blue interviewed almost every major porn star, and regularly hit the limits of what was acceptable for cable television.

“The censorship was always an ‘I-know-it-when-I-see-it’ kind of thing,” says Bennett. “We weren’t out necessarily to get hardcore sex on the air, but rather to get these stories on the air, and some of them were explicit stories. If you do a story about S&M, you’ve got to show it graphically if you’re going to show what it is. You can’t just show a watered-down version.”

He continues, “The politics of the ’60s was predicated on the war in Vietnam, but the real politics of the ’70s was sexual politics. Whether it was gays or women getting rights, it was sexual politics, and it was a very important field at that point.”

After five years of censorship battles—which briefly led to the show being kicked off the air—Bennett left for greener pastures, and Goldstein, who Bennett had tried to keep off camera as much as possible, took over. Midnight Blue was poorer after Bennett’s departure—less ambitious in its reportage, less coherent in its politics—but it did introduce the segment that lives on in YouTube infamy. In “The Al Goldstein Fuck You Department,” Goldstein would deliver petty, venomous diatribes against celebrities (Howard Stern, Linda Lovelace), politicians (Rudolph Giuliani, Ronald Reagan), and even service providers (various dry-cleaners, airlines, suitcase manufacturers, etc.) who stumbled into his ire. Here he is describing Howard Stern…

“Howard Stern this morning was knocking me on the air. Howard Stern wants me to attack him so he’ll feel important. Howard Stern with his long, ugly hippie hair that went out in the ’60s; Howard Stern with his reliance on smut and filth, he has no talent, no wit, he’s not Lenny Bruce. […] And his sidekick Robin—Robin’s like his right testicle. She’s a black chick who looks like a street hooker at the Port Authority terminal. Howard Stern, you aren’t fit to lick the sweat off my Jewish balls!”

And here are some of his thoughts on Regis Philbin…

“Regis, I know people who know you, and you’re one of the most loathsome, disagreeable people in the world. I feel sorry for his wife Joyce who has to close her eyes, open her cunt, and let him put his dick in. You are vile people—I hate your fucking arrogance, I hate your smugness, and you’re what’s wrong with American culture.”

“I like what they did with it … but it became vanity press,” says Bennett. “He was paying a lot of money to go on TV every week.” These rants, so incongruous next to Midnight Blue’s video centerfolds and porn star interviews, became the show’s signature segments.

But then, narcissism was central to Goldstein’s appeal. If Goldstein has anything in common with Hefner, it’s that they both embodied wish-fulfillment fantasies—Hefner with his Playboy lifestyle, and Goldstein with his gleeful, unashamed loathsomeness. It might not be possible to defend Goldstein’s vile rants, but something about them appeals to our pure, selfish id. He had the confidence to be an asshole, and yet nobody was harder on Al Goldstein than Al Goldstein. When he sat in a chair and broke it during a Midnight Blue taping, he ran the footage week after week.

*

If Al Goldstein wants to talk his way into heaven, he could trade on his impressive legacy as a political satirist and “First Amendment Ninja,” to use David Foster Wallace’s description. “I like to think the first 10 or 15 years of Screw led to a lot of positive change,” says Josh Alan Friedman, who worked at the magazine from 1980 to 1985. “Your Aunt Matilda can go down to the corner drugstore now and buy a dildo and nobody would even smirk behind the counter. Well, Goldstein went to jail at one point for putting ads for dildos in Screw. He had to go to court and win in 1970.”

For most of its run, Screw was as political as it was sexual, with Goldstein’s obscenity trials becoming fodder for his editorials, and politicians of every persuasion the target of gross satire (“What This Man Needed Was A Good Screw,” said one subscription ad, over a picture of post-resignation Richard Nixon). In 1969, the magazine ran an article titled “Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?” It was the first time the FBI director’s much whispered-about sexuality had been directly questioned in print. (A popular legend, perpetuated by Goldstein, is that Hoover’s last directive before his death in 1972 was: “Get Goldstein.”) Five years later, Goldstein claimed he received as many of three death threats a day, and had to travel with bodyguards after a would-be assassin broke into the office.

His son, who finished Harvard Law School at the top of his class, was so appalled that he told him not to attend the graduation. The two never reconciled; Goldstein ran videos of his “dead son” on Midnight Blue and told viewers that he’d fucked the dean.

Larry Flynt is remembered for his Supreme Court victory against Jerry Falwell, and Goldstein scored an equally important precedent in 1978, when he was determined not guilty of sending obscene material over state lines into Kansas. The jury acquitted him when the state could not produce anyone who would admit that Screw aroused their prurient interests. The pornographer celebrated by flying sympathetic jurors to Screw’s 10th anniversary party at Plato’s Retreat.

“It was not like The New Republic or Commentary—it was street political,” says Friedman. “It might sound pretentious to say this, but I think he was fighting for the little man at that time. The sanitation workers, the cops, the plumbers, the man on the street who couldn’t get a date with a Playboy model—those guys cheered him. The stuff he did in his weekly editorial for years, attacking every rip-off or phony. It was like the little guy fighting fact against any company that cheated him.”

“We used to have a little sort-of rivalry going on with the Spectator out in San Francisco,” says Eric Danville, an editor in the ’90s. “We were all very happy when they called us ‘New York City’s bohemian egghead porn.’ Alright, I’ll take it.’” At college, Danville had dreamed of working for Goldstein, but by the time he got to Screw, the magazine was past the peak of its relevancy. In the mid-’90s, Rudolph Giuliani launched his campaign against the porn stores in Times Square; the mayor offered plenty of fodder for Screw’s writers, but the sexual world that made Goldstein hip was vanishing. The magazine lost a lot of business when the Village Voice began accepting ads from sex workers, and the rise of the Internet in the late ’90s led to the decline of the men’s magazines across the board. In 2002, he lost his longtime distributors.

It’s hard to tell from the early issues of Screw how much Goldstein’s persona was calculated—it certainly seems a radical transformation from the shy, repressed Jewish boy described by Gay Talese. Whatever he used to be, Goldstein relished his creation, and while his fortunes were declining in the ’90s, he was hard-pressed to admit it. Divorces from his second and third wives in 1991 and 1999 cost him a fortune, and his TV rants against airlines and mail order catalogues were a long way from his First Amendment heyday. Even as Screw’s circulation dropped, he continued to spend. “By the 1990s, it was long over,” says Friedman. “Even by the mid ’80s he just kept it going for the ads so he could keep his life going.”

“Al always treated Screw like it was his back pocket,” says Danville. “We had our skeleton editorial staff, but Al always had a secretary/assistant, his ‘buyer’—he had someone whose job it was just to sit there all day and go through catalogues and see things Al might like, and buy things Al might be finding in SkyMall. He had another guy whose job it was to go to his apartment and set up all the electronics he didn’t know how to fix himself.

“When he found something that he wanted, at his best he had four of them, because he had four houses. For a while he would buy four of everything. We’d walk into the office one day and there’d be four flat-screen plasma TVs and ten boxes of VCRs.”

By the beginning of the 21st century, he’d disappeared so far inside his “Al Goldstein” character that he lost sight of what had once made it important. The old Al Goldstein stood trial for the First Amendment; the new Al Goldstein broadcast his ex-wife’s phone number on Midnight Blue and told people to call her. His son, who finished Harvard Law School at the top of his class, was so appalled that he told him not to attend the graduation. The two never reconciled; Goldstein ran videos of his “dead son” on Midnight Blue and told viewers that he’d fucked the dean. In Screw, he ran doctored photos of mother and son having sex, and asked readers to vote on whether Nixon, bin Laden, Hitler, Arafat, or Mike Tyson was the real father.

But what really finished Goldstein was a 2002 harassment suit from a secretary who was not used to his sense of humour. She quit in a huff; he ran her phone number in Screw, and left a foul-mouthed message on her answering machine promising to “take her down.” In its final months, Midnight Blue’s “Fuck You” segments almost entirely concerned Goldstein’s legal troubles. In his arrogance, he attacked his judge (“You scumbag piece of fucking shit!”) and the New York District Attorney (“I’m taking you all fucking down!”), broadcasting their phone numbers. He ran a doctored photo in Screw of the D.A. sodomizing Osama bin Laden.

In I Goldstein, his autobiography coauthored with Josh Alan Friedman, he regrets not having fallen prey to an assassin’s bullet. “I’m a hologram,” he wrote. “An old condom that someone popped a load into, then threw away.”

Goldstein insisted the harassment charge violated his First Amendment rights. The Judge disagreed, and sentenced him to 60 days in Rikers Island prison in October 2003. When he was released after six days, even Goldstein realized that Rikers was no place for a 65-year-old, 300-pound diabetic. Chastened, he apologized to his secretary. That same month, Screw fizzled out of business, selling only 600 copies of its last issue. He tried to relaunch the brand as a website, but was evicted from his office by federal marshals for non-payment of rent.

*

If you look hard enough, you can spot the ghost of Al Goldstein’s New York. At 8th Ave. and 42nd St., you’ll still find Show World, the biggest sex palace of the ’70s, at one time a multi-leveled labyrinth of magazines, peep shows, strippers and live sex shows. Once occupying 22,000 feet, Show World has been dying a slow death for 20 years, with “Times Scare” occupying where its gaudy neon sign used to be. But it’s still there, in muted form, with a few 25-cent video peeps and some rows of DVDs, where men who don’t have Internet access can stare at the cases and commit images to memory. In the basement, you can buy a crossword puzzle from the stacks and stacks of old magazines; thanks to Giuliani, every Manhattan porn emporium has to stock at least 60 percent non-pornographic content.

Goldstein spent most of 2004 as Manhattan’s most famous hobo, dividing his time between shelters, parks, and all-night Starbucks locations. For a few weeks he found employment as a maître d’ at the Second Avenue Deli, but was fired when he was found sleeping on the kitchen floor. Comedian Penn Jillette, who admired Goldstein’s First Amendment activism, eventually paid for a Staten Island apartment, and supported Goldstein for the rest of his life. In I Goldstein (2006), his autobiography coauthored with Josh Alan Friedman, he regrets not having fallen prey to an assassin’s bullet. “I’m a hologram,” he wrote. “An old condom that someone popped a load into, then threw away.”

When I visited Al at the Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center on December 13, he was wearing padded gloves—the doctors said he’d been pulling out his feeding tube. He was suffering from dementia, but it was hard to tell if he couldn’t understand what was being said to him, or simply refused to talk; he’d been lucid enough six months earlier to deliver a speech at the Cortlandt Alley gallery. The man who once wrote, “Often while lunching out on a daily hooker, my mouth really watered for Pastrami King,” was now refusing to eat, and wouldn’t swallow the milkshake his friend tried to feed him. The man on the bed was skinny and toothless, unrecognizable as the bellowing loudmouth of Midnight Blue.

I’d been warned that Al wasn’t much for conversation anymore by Viveca Gardiner, a New York-based circus entertainer, and one of his few remaining friends. Still, she said, he liked visitors. When we arrived at the hospital, even she was surprised by how quickly he’d declined. Six days after my visit, he was dead from renal failure.

She came to know Al through her friend Penn Jilette. “He told me, ‘Al basically has no one but me and Ratso [writer Larry Sloman]. You don’t want to only have me and Ratso.’” In recent years, she typically visited Al once a week. “He asked to marry me a lot,” she said. “We realized he’s still probably legally married to his last wife, but no one knows where she is.”

I told Al that I was writing about him. He didn’t respond. Occasionally a nurse would come in, rub on Al’s leg, and tell him, “Mr. Alvin, look—you’re surrounded by people who love you.” No one at the hospital knew who he was.

Viveca showed me a cell phone video she had taken of Al within the last year. Al is in a wheelchair, smiling at an off-screen presence. “What did you want to do to me?” the voice asks. “Well,” says Al, with a twinkle in his eye, “First, I’d put my tongue in your vagina, and blow on your pubic hair. Then, I’d lick your asshole…”