When I was 10 years old, I ran away to the circus. Well, with permission.

My family had just arrived at the Club Med in Varadero for six days and seven nights of all-ages, all-inclusive R&R during March Break of 1999. The resort featured a flying trapeze, a brontosaurus of metal poles, rope, and netting—a dinosaur both in size and as a source of entertainment. Had it not been for Dave, the painfully handsome Newfoundlander outfitting guests in safety harnesses, I likely would never have considered trying it, but I had soon mastered the catch-and-release, the back flip off the bar, and performed with the staff in the Friday night talent show.

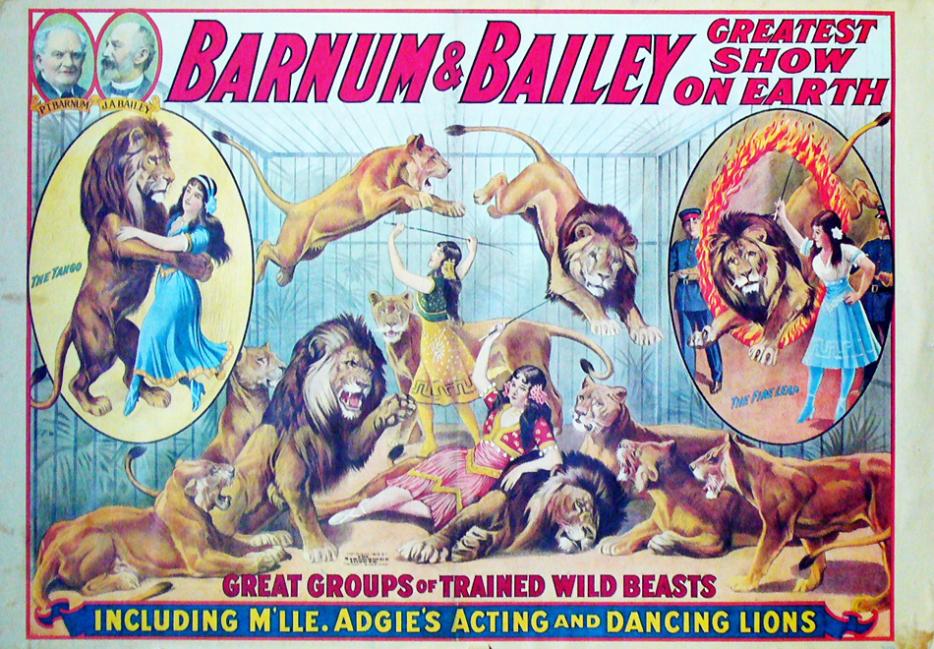

The trapeze became a passionate vacation fling, one that, predictably, ended upon my return home; after briefly whipping through air, my feet eventually landed firmly on the ground of suburban Ottawa. That brief romance aside, the circus seemed to me reserved for those without any other prospects—the criminals and vagabonds, the runaways and freaks. I didn’t put it together at the time, of course, that a tropical resort had gone to the trouble of building a flying trapeze for paying vacationers. These people weren’t sharing a stage with Barnum & Bailey’s musical donkey, though neither were they driven by the desperation many of that era’s performers faced—they didn’t have to develop their talents on the margins or rely on them to be passed down through family lines. They showed that these skills, for better or for worse, could be practiced by anyone, something to do in between margaritas and aqua aerobics.

“In Montreal, everyone’s dentist also does clowning on the weekend,” says Duncan Wall, author of the new book, The Ordinary Acrobat. Wall had a similarly antiquated perspective of the Big Top until he was introduced to the “modern circus” in France, the global centre of the circus arts. A juggler reciting Proust, acrobats singing Simon and Garfunkel, a flyer that resembled something meant for “a band or a contemporary dance show than for a circus”—that one evening of performance eventually led this guy from St. Louis, with no circus experience whatsoever, to spend a year studying at Paris’s École Nationale des Arts du Cirque on a Fulbright Scholarship. The Ordinary Acrobat documents that year as well as the rise, fall, and reincarnation of the art form that has only recently broken back into the mainstream. “The performers were open, even welcoming,” he writes. “Most of them had grown up in ‘regular’ families, and as adults, lived ‘regular’ lives. They rented apartments in Paris and drove their kids to school. For fun, they attended movies and art gallery openings. In fact, their normality was probably what attracted me most: the modern circus life was a life I recognized.”

Today, he recognizes it as his own life. He just completed his first year as a teacher of circus history and criticism atMontreal’s National Circus School, a world-renowned training institution that celebrated its 30th anniversary last year. Enrollment now boasts over 150 full-time students and an employment rate of 95 percent within three months of graduation. Even as Cirque du Soleil eliminates 400 jobs and closes several of its shows, the school is apparently still having trouble meeting the demand for professional circus performers around the world. While I forgot my brief dalliance with the trapeze and pursued journalism in an attempt to secure a solid financial future (whoops), circus performers continue to find work in an increasingly mainstream art form, landing at large-scale spectacles like Cirque and the equestrian-based Cavalia, cabarets in Germany, independent troupes in North America, niche fitness classes, and other gigs with corporate events, cruise ships, and nightclubs.

“The irony about being a circus performer today is that it’s not saturated,” Wall says. “Like dancers—dancers are desperate for a chance to perform, period. Whereas circus performers are still doing quite well because there are all these extracurricular places where they can make money.” Talking to him, the comparison between contemporary circus performers and professional athletes or dancers comes up quite often—and it’s the former career path that seems to offer the most stability. Circus performers don’t suffer from expiration dates on their careers; jugglers and clowns can work well into their 60s. And, according to a 2009 study in The American Journal of Sports Medicine, the risk for major injury in the circus arts is much lower than in any college-level sports association.

The biggest similarity between dance, sports, and circus acts—and perhaps the biggest departure from the traditional circus—is the now common need for formal training from places like Montreal’s NCS and Paris’s ENAC. Potential circus performers aren’t running away to fulfill their dreams anymore—they’re being driven to auditions by their “dowdy” parents dressed in khakis and windbreakers. As Wall writes of that older class of performer-in-training, “The kids who had enrolled tended to be those who struggled in traditional academic settings. Rebels themselves, they were attracted to the circus’s outsider reputation. Today this has changed.”

Circus staff and performers once commonly referred to themselves as a “family,” and not just because acts were traditionally inherited through one’s genealogy. These groups functioned as part of a larger and complete society, descending upon a town for a few days, one after the other. It was a society sometimes accused of witchcraft, as Wall writes, and other times banned outright, but a society nonetheless—one with its own language, values, and customs, one that built and dismantled its own infrastructure in a matter of hours. Today, the regimented protocol of Cirque du Soleil is great for business, but lacks for romance. “The performers fly in on airplanes and sleep in high-priced hotels,” Wall writes. “The troupe’s village is organized and secure.”

Even the myth-making fiction is changing. “During the low period of the circus, the circus itself as a performance form, people weren’t really interested in that,” Wall says, “so books would come out every year and movies would come out every year, but they would never be about what happened in the ring, It would always be about what happened behind the tent. That has obviously shifted, which is better to a large degree, because the emphasis is on the art. But it’s also kind of sad because it’s a bit like a culture is dying, like a kind of tribe has passed on.”

Though Cirque does have its detractors who criticize its quest for commercialism. Some of its students adopt a hippie persona, Wall observes, that’s “more like a style than a lifestyle.” Meanwhile, many legendary families have had to find new roles in the changing circus dynamic, either joining the more modern companies or beginning new lives as Broadway producers. Traditional circuses do still exist, filling the void of the nostalgic aesthetic of the circus of children’s books and French vocabulary lessons for the fans that show up, but the number of contemporary shows vastly outnumber them. And their contemporary counterparts, after all, don’t face protests of animal cruelty at virtually every stop.

In the traditional circus’s prime, its performers were adored as celebrities in what was then one of the most popular forms of entertainment. Equestrian acrobat May Wirth made headlines in The New York Times when she, after pulling off a double somersault on her white Arabian, Juno, fell and was dragged around the ring four times in 1913. Napoleon had a nickname for tightrope walker Madame Saqui, “mon enragée” (“my little lunatic”). Circus fans made pilgrimages to the Père Lachaise grave of Philip Astley—the “father of the circus.” But with the rise of radio and television, the circus, and its performers, lost their elite status. The ascendance of the modern circus only the most recent high point on the merry-go-round of circus history, one that reflects yet another change in audience desires—what we want now is not so much an escape but, rather, a kind of artistic experience that’s more five-star than five rings.

Those dusty, sepia-toned images of roguish circus life are fading, and coming into focus are the realities of a highly structured learning process, a flourishing industry, and virtually guaranteed employment—the unique romance of danger and exclusivity giving way to a cordial rigidity. And yet, I can’t mourn that change wholesale. That day on the trapeze, though I didn’t know it at the time, I did become part of the circus movement—the “new circus,” the one that welcomes newcomers, that commands respect and attention without the aid of a carnival barker, that revels in and relies on an intense appreciation of its artistry. It’s one of the rare flings I could easily rekindle today, 14 years later—less exotic and mysterious than it might have been a century ago, but a love story all the same.