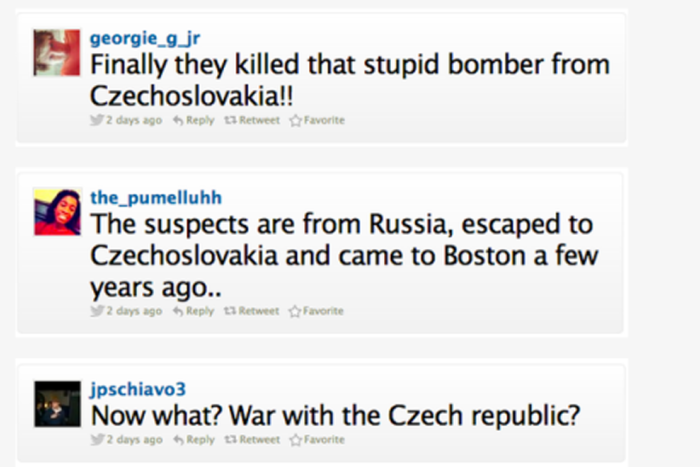

After brothers Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were identified as the likely bombers behind last week’s Boston Marathon attack, pundits raced to interpret their actions through many filters—their Chechen heritage among them. As the New Yorker’s Amy Davidson writes, though, jumping immediately to such conclusions is a mistake, one that invites a serial misunderstanding of a conflict as lengthy and complicated as the one between Russia and Chechnya. Context, as always, is everything: Here are five essential reads on the decades of strife in the Caucasus.

I AM A CHECHEN! (2010) by German Sadulaev

There is no shortage of literature written in the Caucasus region, but little of it is translated into English. Kapka Kassabova, writing in the Guardian, hailed Sadulaev’s fictionalized memoir of life during the Russian-Chechen wars of the late 20th century as a “welcome antidote to our collective ignorance.”

It’s hard to be a Chechen. If you’re a Chechen, you must feed and shelter your enemy when he comes knocking as a guest; you must give up your life for a girl’s honour without a second thought; you must kill your blood foe by plunging a dagger into his chest, because you can never shoot anyone in the back; you must offer your last piece of bread to your friend; you must get out from your car to stand and greet an elderly man passing on foot; you must never run away, even if your enemy are a thousand strong and you stand no chance of victory, you must take up the fight all the same. And you can never cry, no matter what happens. Your beloved women may leave you, poverty may lay waste to your home, your comrades may lie bleeding in your arms, but you may never cry if you are a Chechen. If you are a man. Only once, once in a lifetime, may you cry: when your mother dies.

At the very beginning of the war, my elder sister asked our parents to join her in Novorossiysk. Mama and Papa didn’t want to, they still believed that the war would be short, that it was all a terrible mistake, a misunderstanding, and would be over soon; they didn’t want to abandon their native soil. They went to visit my sister, watched television, believed it again when military operations were said to be at an end, and returned home despite their daughter’s pleas. This happened many times over, until finally our parents decided to stay with her. So they moved, leaving our second sister, Zarema, behind in Shali. Zarema had married and flatly refused to leave.

After a long, difficult life, after a terrible war, Mother and Father spent three years in Novorossiysk, their happiest years. Until then something or other had always got in the way, stopping them from simply being together. First there was work, Father’s drinking with colleagues, guests, quarrels with relatives. Then prison. And the war. But all that had passed. Mama was already blind, severely ill, how could they have been happy? Yet they were. All day long Father was with Mama. They chatted, no longer hurried anywhere. Every evening he took her arm and they would go out for long walks, especially during the summer when the south makes you drunks with its scents and dizzy with its warmth. All the neighbours looked at them in fond envy, the couple in love, together for more than thirty years.

When Zarema was wounded, Mama’s condition began to deteriorate alarmingly. That surface-to-surface missile brought death nearer, cost my father and mother several years, several years of true happiness. With a year Zarema was much better, she was almost cured, but Mama … Our elder sister called, and we flew from St Petersburg that very day. When we reached the apartment, Mama was still alive, or … I’m not sure. Could she hear us, did she realize that we were near her? Could she feel me holding her hand? Mama was in a coma all night. She passed away in the morning.

In the house the mirrors were covered, so I didn’t see myself. My sister looked at me and said, ‘Your temples are grey.’ I’d turned grey overnight.

And I cried out my tears. Just once in a lifetime a man may cry, and at that time he cries out all his tears, a whole lifetime’s worth, for all that has been and all that is yet to come.

In the morning I went outside and looked at the world. Feeling a light, ringing hollowness. There was no more fear. That morning I stopped being afraid. Nothing bad can happen now. It has all happened already. There will be no more tears. I shall never cry again.

*

RUSSIA: THE ONCE AND FUTURE EMPIRE FROM PRE-HISTORY TO PUTIN (2006) by Philip Longworth

Longworth tells the story of a Tsarist expedition in the Chechen village of Dadi-Yurt on September 15, 1819 that ended in a massacre.

On the mountaineers’ side the war was total, fought to the death. Baddeley described an encounter relatively early in the war, when the Chechen village of Dadi-Yurt was attacked. Since every house was guarded by a high stone wall, it had to be pounded by artillery and kept under relentless small-arms fire. Once a breach was made, soldiers rushed in, but were met in the dark by Chechens wielding daggers. ‘Some of the natives, seeing defeat to be inevitable, slaughtered their wives and children … Many of the women threw themselves onto … [the soldiers] knife in hand, or in despair leaped into the burning buildings and perished in the flames.’ The Russian commander proposed a parley, but the answer, given by a half naked Chechen, black with smoke, was ‘We want no quarter.’ ‘Orders were now given to fire the houses from all sides. The sun had set, and the picture of destruction and ruin was lighted only by the red glow of the flames. The Chechens, firmly resolved to die, set up their death-song, loud at first, but sinking lower and lower as their numbers diminished.’ Eventually some broke out, preferring to die from bullets or the bayonet rather than burn to death. Some Dagestanis who were with them were captured, but ‘not one Chechen was taken alive.’ Seventy-two men ‘ended their lives in flames.’

*

THE REVENGE OF GEOGRAPHY (2012) by Robert D. Kaplan

Kaplan, citing geography as an underrated factor in geopolitical tensions of the past, present and future, outlines the location-based grievances that helped inflame the Russian-Chechen conflict.

“To this day we look upon Europeans and upon Europe in the same way as provincials look upon those who live in the capital, with deference and a feeling of our own inferiority, knuckling under and imitating them, taking everything in which we are different for a defect.” — Alexander Herzen

Though Russians should have had nothing to be ashamed of, for they could only be what they were: a people that had wrested an empire from an impossible continental landscape, and were consequently knocking at the gates of the Levant and India, thus threatening the empires of France and Britain. For at about the same time that Herzen wrote those words above, Russian forces took Tashkent and Samarkand on the ancient silk route to China, close to the borders of the Indian Subcontinent.

Whereas the maritime empires of France and Britain faced implacable enemies overseas, the Russians faced them on their own territory, so that the Russians learned from early on in their history to be anxious and vigilant. They were a nation that in one form or another was always at war. Again, the Caucasus provide a telling example in the form of the Muslim Chechens of the north Caucasus, against whom the armies of Catherine the Great fought in the late eighteenth century, and continued fighting under succeeding czars throughout the nineteenth, to say nothing of the struggles in our own time. This was long after more pliable regions of the Caucasus further south, such as Georgia, had already come under czarist control. Chechen belligerency stemmed from the difficulty of earning a living from the stony mountain soil, and from the need to bear arms to protect sheep and goats from wild animals. Because trade routes traversed the Caucasus, the Chechens were at once guides and robbers. And though converts to Sufi Islam—often less fanatical than other branches of the faith—they were zealous in defense of their homeland from the Orthodox Christian Russians. In the Caucasus, writes the geographer Denis J. B. Shaw, “the Russian, Ukrainian and Cossack settlement of the ‘settler empire’ came into conflict with the stout resistance of the mountain peoples. Most of these peoples, apart from the majority of the Osetians, are Islamic in culture, and this reinforced their determination to fight the Russian intruder.” Because of their fear of the independent spirit of the people of the north Caucasus, the Bolsheviks refused to incorporate them into a single republic and split them up, only to rejoin them into artificial units that did not conform to their linguistic and ethnic patterns. Thus, Shaw goes on, “the Karbardians were grouped with the Balkars, despite the fact that the former have more in common with the Cherkessians and the latter with the Karachay.” Stalin, moreover, exiled the Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks, and others to Central Asia in 1944, for their alleged collaboration with the Germans.

*

THE SCHOOL (Esquire, March 2007) by C.J. Chivers

Chivers reconstructs a Chechen terrorist group’s attack on a school in the Russian town of Beslan in 2004, in which over a thousand people were taken hostage for three days and hundreds died.

The terrorists appeared as if from nowhere. A military truck stopped near the school and men leapt from the cargo bed, firing rifles and shouting, ”Allahu akhbar!” They moved with speed and certitude, as if every step had been rehearsed. The first few sprinted between the formation and the schoolyard gate, blocking escape. There was almost no resistance. Ruslan Frayev, a local man who had come with several members of his family, drew a pistol and began to fire. He was killed.

The terrorists seemed to be everywhere. Zalina saw a man in a mask sprinting with a rifle. Then another. And a third. Many students in the formation had their backs to the advancing gunmen, but one side did not, and as Zalina sat confused, those students broke and ran. The formation disintegrated. Scores of balloons floated skyward as children released them. A cultivated sense of order became bedlam.

Dzera Kudzayeva, seven, had been selected for a role in which she would be carried on the shoulders of a senior and strike a bell to start the new school year. Her father, Aslan Kudzayev, had hired Karen Mdinaradze, a video cameraman for a nearby soccer team, to record the big day. Dzera wore a blue dress with a white apron and had two white bows in her hair, and was on the senior’s shoulders when the terrorists arrived. They were quickly caught.

For many other hostages, recognition came slowly. Aida Archegova thought she was in a counterterrorism drill. Beslan is roughly 950 miles south of Moscow, in a zone destabilized by the Chechen wars. Police actions were part of life. “Is it exercises?” she asked a terrorist as he bounded past.

He stopped. “What are you, a fool?” he said.

The terrorists herded the panicked crowd into a rear courtyard, a place with no outlet. An attached building housed the boiler room, and Zalina ran there with others to hide. The room had no rear exit. They were trapped. The door opened. A man in a tracksuit stood at the entrance. “Get out or I will start shooting,” he said.

Zalina did not move. She thought she would beg for mercy. Her granddaughter was with her, and a baby must mean a pass. She froze until only she and Amina remained. The terrorist glared. “You need a special invitation?” he said. “I will shoot you right here.”

Speechless with fear, she stepped out, joining a mass of people as obedient as if they had been tamed. The terrorists had forced the crowd against the school’s brick wall and were driving it through a door. The people could not file in quickly enough, and the men broke windows and handed children in. Already there seemed to be dozens of the terrorists. They lined the hall, redirecting the people into the gym. “We are from Chechnya,” one said. “This is a seizure. We are here to start the withdrawal of troops and the liberation of Chechnya.”

*

THE INSURGENCY IN CHECHNYA AND THE NORTH CAUCASUS: FROM GAZAVAT TO JIHAD (2010) by Robert W. Schaefer

Though he insists the book not be read in a vacuum, Schaefer attempts to “get past the politics, the rhetoric, the tactics, the value-judgments, the disinformation, and the condemnations” in this thorough accounting of the decades of war between Russia and Chechnya.

Unlike conventional wars where the strategic goal is to destroy the enemy’s will to fight through fire and maneuver, the goal in an insurgency is to win the support of the populace through a war of ideas, or legitimacy. Whoever controls the “mass base” generally wins. The insurgency does everything it can to destroy the legitimacy of the seated government while simultaneously asserting its own legitimacy based on its promises that a new insurgent government will better serve the needs of the people. To counter this threat, the government—not the military—must conduct a counterinsurgency campaign that attempts to point out that the insurgents are criminals and terrorists that are only interested in gaining personal power while simultaneously addressing the population’s concerns about security and access to resources.