Cabinet magazine recently celebrated ten years of putting curiosity on the printed page, and to mark the occasion they’ve released a door-stopping compendium to direct readers through a decade of miscellany. Curiosity and Method: Ten Years of Cabinet Magazine is a self-conscious encyclopedia, announcing itself as a book that aims to take both the long and short view. Just like the magazine, it collects writing on all manner of minutia from academics, essayists, and journalists. Also just like the magazine, it takes an antiquated interest in what true wonders remain in our information-saturated world.

The pleasures of a discrete body of knowledge, a compendium of what is or may be known, are fleeting; as soon as the pixel or ink takes shape, the idea behind the sign opens itself up for contestation. It’s as if once information got on the highway, it refused to ever stand still again. Curiosity and Method, thankfully, makes for a welcoming, even delightful, readerly rest stop. Rather than adhere to today’s pace of the flow of information, the book invites you to pause and pore over a more whimsical and rewarding approach to knowledge. Open ‘er up and let your eyes fall where they may; flip decadently from the entry on syncretism backward to the one on balloons. You might learn something in the process, or you might not. That’s not precisely the point. The goal is to stimulate an appetite for the curious and unnecessary, to delight in the weird and the niche—here, the only way to hit the target is to wander without aim, to search without terms and find without optimization. You yourself become the engine that searches.

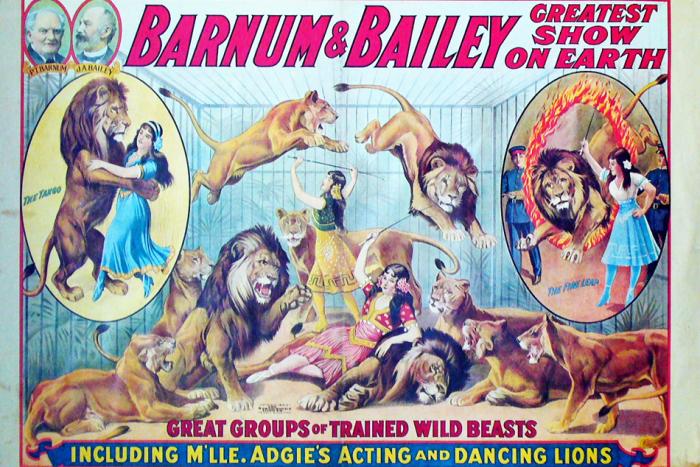

Cabinet, the magazine, marries the Victorian impulse to dissect and to display a fundamentally Dadaist dedication to the absurd. And so too does the book—the launch party for Curiosity and Method, as Sasha Frere-Jones noted recently in Bookforum, echoed a mock trial first held in 1926. The printed encyclopedia is a relic from another era, a fact that Cabinet celebrates; it’s as if the pressure of relevancy is relieved, all that’s left is the joy to be had in simple, beautiful reference. But rather than simply borrow the conventions of another time, Cabinet inverts and so reinvents them. If there is no need to catalogue this miscellany of conceptual art, historical artifacts (and practices), and literature as self-seriously as the intrepid armchair scholars and arrivistes of yore, then why not instead delight in the friction that comes from context? If you wondering about the Devil, for instance, you might not find him after the listing for dentistry—rather he’ll find Denis Johnson under the Tarot (Satanic) heading.

The classically cross-referenced printed encyclopedias of the past are proven not only useless in these times, but horrifically dull next to the wonders that might have been. Right after I was born, my mother bought me a Children’s World Book encyclopedia set. The many-volume collection followed me all through elementary school, and later I would often grab one to flip through during the commercials while watching TV shows. It was an early and autodidactic education in the benefits of taking a high-low look at the world, pairing reading about, say, feline musculature with Boy Meets World. I can still remember the detailed illustrations of the human sexuality entries, which were accompanied by tiny, informative essays on puberty and illustrations of tall preteen girls with small but prominent breasts towering over their male peers. Obviously, those particular pages especially gripped and titillated my young imagination above the ones detailing the process of wheat harvesting.

In middle school, my pockets lined with babysitting money, I bought a conspicuously adult encyclopedia set for $15 at a used bookstore. The 1961 edition of the World Book was green and cream and I intended to read every volume. I made it most of the way through “A,” but Cold War-era atomic knowledge was both too dry and too spooky. By high school I would become an avid Wikipedia reader—it was still brand new back then!—and the world’s only been getting bigger, but somehow less navigable ever since.

In the preface to Curiosity and Method, the editors tell us that the volume is intended to be used for reference, but then go on to cite reference as a dominant problem of criticism and trace a delicious historical overview of the word from semiotic, etymologic, theologic, and even metaphysical viewpoints. “Thus it is important to remember that whenever we make use of a reference work—indeed, whenever we refer—we are reaching back toward the kind of anomalous, streaking body that burns itself out across a nearly instantaneous, violent transit between worlds.” It’s there in the transit that one might find a moment of true repose—a place to rest that nonetheless keeps the body of knowledge in motion.