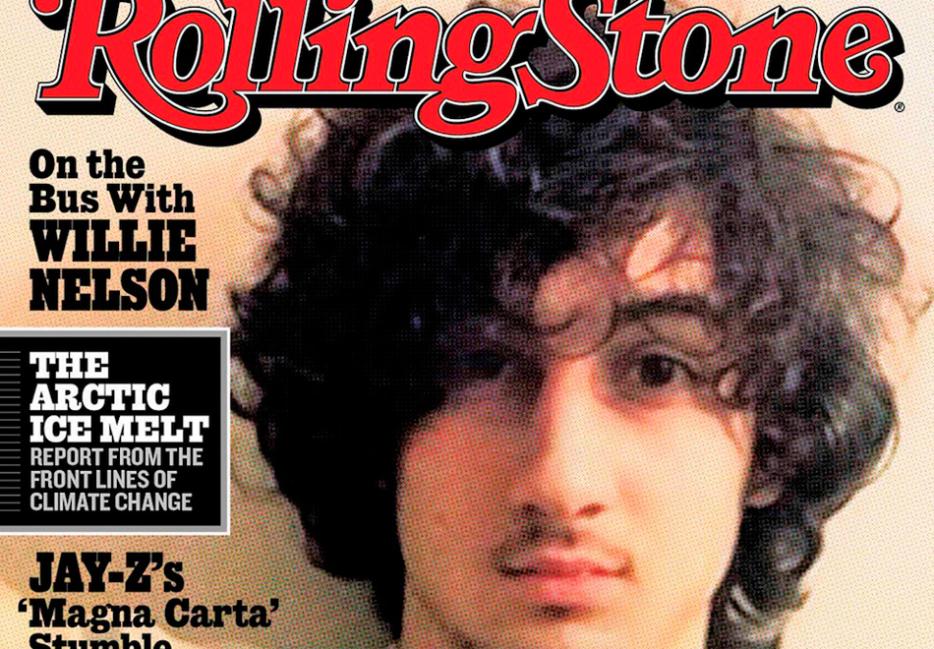

Putting Dzokhar Tsarnaev on the cover of Rolling Stone was not a bad move. It did not make terrorism seem sexy. It wasn’t even sensationalistic. The widespread outrage from the egregious misreading of that cover, before the story was even put online, went beyond absurd into the profoundly worrisome.

We have, apparently, turned into a culture of media idiots.

It’s like this: Imagine, if you will, that all those climate-change fraudsters are not as wrong as they obviously are, and the world’s water levels continue to rise. Imagine not only the Maldives and Miami gone, but water creeping up into every continent. There’s less and less land, and we are more and more dependent on water-born forms of transportation for our daily commutes and errands.

Now imagine at the same time everyone forgets how to swim.

We’re swamped in media right now, but we seem less capable than ever of keeping our heads above water. Not so long ago, if you read three papers a day, you were some sort of super-informed megastar. People would gather around your desk at work for the pearls of wisdom that would drop from the lips of someone so widely read.

These days, I read upwards of 20 publications a day, sometimes a good deal more, and my Facebook and Twitter feeds are still filled with people who leave me in the dust. My circle and I may be more avid media consumers than average, but I doubt many people in this part of the world read from as narrow a selection as those poor three-paper-a-day slobs of yesteryear.

And yet, just as various media increasingly occupy our daily lives, becoming the fodder for our opinions, our conversations and our social media activity, we seem to have lost the basic essentials of media literacy.

There was a time when, if Earl Cameron or Walter Cronkite said something, the average person figured it had to be true. There was some movement in the 1980s and ’90s towards a more critical form of literacy, but that had barely found its feet before it was washed away by the Internet deluge. Or, at least, worn down to an edgeless smoothness that manifests itself as simple, thoughtless reaction.

Like with the Tsarnaev cover.

It’s not as if Rolling Stone went searching through yearbooks and Facebooks to find the sexiest possible picture, thereby throwing this accused bomber into a different and more sympathetic or glamorous light. We’d all already seen this picture, and a dozen others that let us know he was not a bad-looking dude.

I’m usually skeptical of the sort of letter from a publisher or editor defending against this or that outrage. They’re usually disingenuous. But the only message published above the article when it eventually went online was simple, clear and true: They put him on the cover because he looked a lot like the people who read the magazine. They thought the effect of offering their readers this kind of mirror, followed by a well-reported investigation into the route Tsarnaev took from pot-smoking slacker to alleged limb-shearing Musloon was potentially profound. It may still be profound, if they can get past the cover-as-controversy meme that now cloaks it.

Magazine covers, along with newspapers’ front pages, have long been powerful print devices, and categorically different from the rest of the medium. They’re sales tools, true, but they’re also declarations of principles—statements of intent, cultural objects all their own. And they have intentionally courted controversy. Take Esquire’s April 1968 cover image of the conscientiously objecting Muhammad Ali as St. Sebastian, National Lampoon’s January 1973 “If You Don’t Buy This Magazine We’ll Kill This Dog,” or Playboy’s October 1971 cover featuring its first black Bunny. The king of them all, though, is probably Time Magazine’s 1938 “Man of the Year” cover, featuring a drawing of Hitler playing an organ while corpses revolve on a macabre Catherine wheel. Hitler? Man of the Year? Why, that’s anti-Semitic, enemy-comforting treason!

Oddly, newsstands did not refuse to sell it, as they have with this current issue of Rolling Stone. Media competitors did not create or fuel a backlash, as they have done this past week or so. Nobody is even on record as demanding the magazine donate that issue’s profits to B’nai B’rith.

News is often made by unsavoury people. As a result, they often warrant cover/front-page treatment. The year afterTime made Hitler Man of the Year, it was Stalin, who went on to make another appearance in 1942. As late as 1979, their Man of the Year was Ayatollah Khomeini, with barely a ripple of popular lumpen discomfiture. But in 2000, when they were deciding whom to name Person of the Century and, by all indications of their own standards for influencing an era, Hitler was probably once again their guy, they instead opted lamely for Einstein, with Gandhi as runner-up. Einstein, a scientist whose theories were already being disproved in 2000, and Gandhi, who, though of enormous importance to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the former British empire, had little effect in the US or most of the rest of the world. Time had caved to the same sort of frothy thinking that’s been drawn out by the Tsarnaev cover.

We’re hobbling our own media, contorting it into the twisted image of our malformed understanding of it.

It being Rolling Stone, I would write off the whole mess as a special case born of the continuing Shel Silverstein/Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show-fuelled glow that particular cover space occupies in our culture, if we hadn’t already heard the nonsense about Luka Magnotta, and Paul and Karla before him. The fact is, some people are just prettier than others, and some pretty people do some pretty ugly things. This is not a reason not to print their pictures. If anything, it’s an imperative to do just that—to uncouple our basic instinct that pretty people are better people as the dominant justification for why we want to fuck them.

Putting Dzokhar Tsarnaev on their cover was not only not wrong, not craven, it was one of the best, most layered and most effective editorial decisions made by the mainstream press this year. Or it would have been, if the general public hadn’t disappointingly failed to rise to the relatively modest editorial challenge of a damn rock and roll magazine.