The waterfront park in my hometown of Windsor, Ontario, is a five-kilometre long stretch of lawns and gardens that runs along the Detroit River. There’s even a remarkable collection of public art sculptures—a flying saucer, a mermaid on a pole in the river, a giant hand holding a green apple, but the only superstar here is Detroit, its Gotham-like rump of a skyline there on the other side. Its considerable bulk appears on the horizon as you approach Windsor by car, visible before its closer Canadian neighbour. Even the Queen, when she visited Windsor in 1984, looked across the river at Detroit and mistakenly marveled aloud at our impressive skyline; the far-flung edges of empire get as blurry as the border itself in a place like this. With Detroit declaring bankruptcy, it’s like an old friend we’ve all watched decline over the decades has taken another very public fall; if a city could wince, Windsor certainly would.

Detroit preoccupies Windsor. Windsorites go to the river and watch the lake freighters float by in front of Detroit. Detroit newspapers are read. The local ginger ale, Vernors, is consumed. The 72-storey Marriott Hotel in the middle of the Renaissance Center, a 1977 collection of skyscrapers meant to rejuvenate a declining downtown Detroit, helps Windsorites know which way is north. Meteorologists on Detroit TV channels come into everybody’s home and teach Fahrenheit so well that we will forever be converting Celsius in order to really know what the temperature feels like, as I do even though I’ve been living in fully metric Toronto for thirteen years.

Windsor’s waterfront provides the best view of America from anywhere in Canada, but the relationship is much deeper than just the skyline. People in Windsor know Detroit the way they know their own city. In many ways, it’s the same city—just one with a rather inconvenient international border running through the middle, requiring citizens to produce papers for a customs agent, a kind of less-fraught Berlin Wall experience ever since 9/11 complicated once-easy border crossing. There’s cross-border dating, cross-border friendships, families that fall on both sides of the river. Sundays in Windsor, cars with Michigan plates will be parked in driveway after driveway, no shortage of international domestic mixing on people’s downtime. On weekday mornings, rush hour crowds both the bridge and tunnel as Windsorites head to Detroit to work as nurses, teachers, engineers. Some radio stations in Windsor even cater to an American audience, running Detroit commercials and less Canadian content than other parts of Canada are required to play, thanks to a local CRTC CanCon exemption.

Windsor folks were some of the luckiest in Canada during the 1980s and ‘90s, able to slip over the border late in the evening to go to techno parties thrown in old factories or warehouse buildings where legendary Detroit DJs would spin. Those industrial spots were some of the few places, like sporting events, where Detroit’s incredible racial divide and de facto segregation above and below 8 Mile Road didn’t seem to matter. Windsorites have always gone to Detroit for culture, to see big-name concerts and smaller-venue bands. Trips to foreign films at the ornate Detroit Institute of Arts theatre are part of Windsor life, too, as were the trips we made to jazz bars deep in Detroit where sometimes we would be the only white people in a crowded club but were always welcomed warmly.

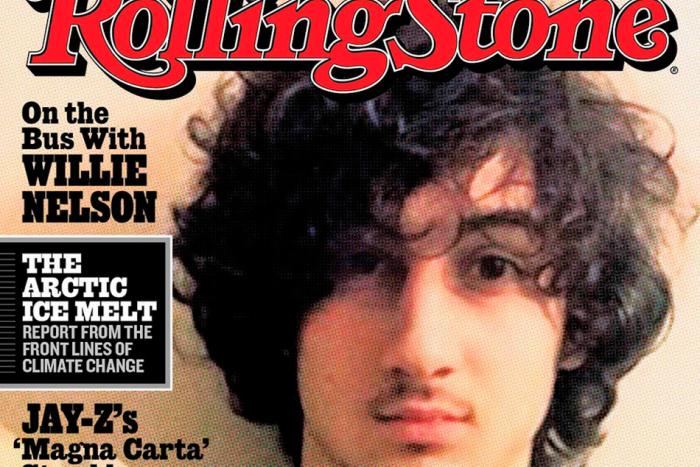

You haven’t been to a dance party or rock show until you’ve been to one in Detroit, borne witness to an enthusiasm that isn’t always present in other cities. It’s like what Bob Seger famously said on his 1976 album, Live Bullet, recorded in concert at Cobo Arena downtown: “I was reading in Rolling Stone where they said Detroit audiences are the greatest rock and roll audiences in the world. I thought to myself, ‘Shit, I’ve known that for ten years.’” Even the hipsters move at concerts in Detroit. On either side of 8 Mile Road, the split between Detroit and its suburbs, between black and white and rich and poor, there’s a pride of place and loyalty to the region that is remarkable and fierce.