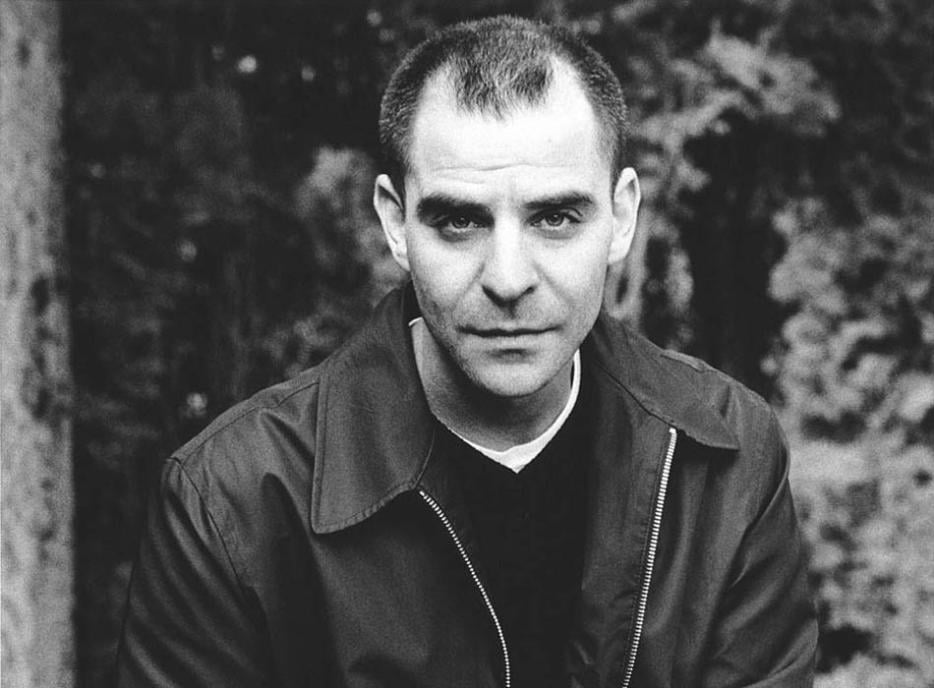

David Rakoff, the dusky-voiced writer of mordantly funny personal essays, died earlier this month from what he once called “a touch of cancer.” In his last essay collection, Half-Empty, Rakoff wrote, “I am still not moved to either pray or ask “Why me?” explaining later, in an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, that “the universe is anarchic and doesn’t care about us…Since there is no actual answer as to why me, it’s not a question I feel entitled to ask.” A similar sentiment appears in Christopher Hitchens’ posthumous collection Mortality. After being diagnosed with esophageal cancer, the vitriolic British essayist wrote, “To the dumb question, ‘Why me?’ the cosmos barely bothers to reply ‘why not?’”

In their early careers, the two could never have been categorized together. Rakoff was an observer of farce but never a participant, bemused but never outraged, sacked with that particularly Jewish tendency towards self-flagellating neurosis and skittish retreat. Hitchens, a longtime columnist for Vanity Fair and professional shit-disturber, was a bullish libertarian who never wavered from his paroxysmal rhetoric and who got into the ring as much as he announced from the sidelines. Rakoff was the prophet of anxiety, Hitchens of bombast; Rakoff questioned, Hitchens told. While both were atheists, Rakoff’s writing on religion found light in believers’ humanity in spite of their dogma, whereas Hitchens openly condemned all religious doctrine.

In their end-of-life writing, however, both men struggled with the same question of how to await death in a godless world. In doing so, they reinvented the way we write about death, which is no longer the province of sublime exaltations and solemn majesty. Gone are the ethereal martyrs dying with smiles on their faces as they meet God. Death, for blessed heretics like Rakoff and Hitchens, is neither graceful nor dignified. They don’t fear it—since there’s nothing afterward, there’s no reason to be afraid—but they resent it. And that both memoirs drip with resentment only makes them more powerful, resentment being one of those gloriously facile emotions that make us humans and not saints.

Hitchens and Rakoff transform death into something prosaic, focusing on their most earthly assets: their bodies. Without the promise of an afterlife, they treat death with the same exhausted disdain as they would any of life’s other hassles. Their memoirs are tactile as they describe the physical impact of cancer, shudder-inducing as they recount the quotidian losses of minor daily dignities, a little bit gross as they describe some of the messier side effects of treatment, and blessedly human as they whine and gripe about the often hilarious, often gut-punching inconvenience of meeting one’s demise.

For the sake of journalistic integrity, I should confess that Rakoff and I had a personal connection. Not one that he knew about, but a one-sided, aching friend-crush on my end. I read Rakoff, an obscure, perhaps off-puttingly melancholy humourist, the way many twenty-something women my age read Joan Didion: with a combination of idolatry and identification. I saw him as my idealized self—an anxious introvert like me, but one with the Riesling-dry wit and cool-headed self-awareness that I lacked. I wanted to hang out with him, sure, but more than that I wanted to be him.

My own narcissistic, imaginary relationship with Rakoff aside, he’s been a champion for the anxiety-spectrum-disorder community by normalizing negative thinking in an era when it’s seen as a character flaw. He wrote that, as a child, he was afraid of everything: “dogs, heights, subways, crowds, snakes, the dark, elevators, tunnels, bridges, spiders, flying, loud noises, roller coasters, amusement-park midways, the ruffians who hung around same, horror movies, fireworks, rock music that seemed to glorify chemical abandon, balloons blown up too big, changing lightbulbs, athletes, going down into the basement.” As an adult, that translated into “defensive pessimism,” a worldview in which, by girding yourself for the worst-case scenario, you’re better equipped to handle the actual outcome (and pleasantly surprised when it’s not as bad as you predicted). He spoke of “contentedly worrying,” which sounds like an oxymoron, but isn’t. In Rakoff’s case, and in my own, worry is comforting and somewhat invigorating. If I’m not worrying, there’s something wrong.

Considering the structure of Half-Empty—which opens with a manifesto on defensive pessimism—its final essay, recounting his diagnosis and subsequent treatment, feels like an inevitable bookend. Rakoff feels it, too: his defensive pessimism has finally run its course, and the worst possible outcome is, in fact, the outcome. “The diagnosis carries with it not a sense of relief, really…so much as a kind of egocentric ‘of course.’ It fits with an inarticulate but ever-present sense that I have done something wrong; an infraction, inadvertent but inescapable and deep as oak roots, marring my permanent record permanently.”

In the 19th century, death wasn’t so bleak, and writing about death was statelier, with the same bittersweet ring of acceptance as if describing someone leaving a job for a higher-paid gig. The dead will be missed, but they’re going somewhere better. Wordsworth’s Lucy, for example, ends up in heaven. Same with Tennyson’s A.H.H. and Shelley’s Adonais (whose name is a stand-in for God). Upon learning of his illness and being told that his arm and shoulder would have to be amputated, Rakoff tries to latch onto this outdated notion of martyrdom, and to revel in how much fun it was. He remembers two of his favourite 19th-century fairy tales. The first, Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf” tells of a monstrous child who descends into hell, meet’s Satan’s bubby (“not surprisingly, a total fucking bitch,” says Rakoff) and eventually gets to heaven after repenting. The second is Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince,” about an unbearably virtuous statue and his friend, the sparrow (also pure of heart), who suffer for the sake of others and get escorted by God’s personal envoys to the pearly gates. Rakoff, the gay New York Jewish son of psychiatrists from Toronto, swiftly dismisses any possibility of heavenly ascension. “Is it any wonder, then, that I should feel destined for great things?” he asks after his diagnosis. “And by great, of course, I mean terrible.”

Hitchens, who has, of course, been outspoken about his atheism, comes, not surprisingly, to the same conclusion. “Random caprice will still determine whether or not you receive a heavenly reward,” he writes plainly. He takes pleasure in needling the Internet trolls who say God is punishing him. “Why not a thunderbolt for yours truly, or something similarly awe inspiring? The vengeful deity has a sadly depleted arsenal if all he can think of is exactly the cancer that my age and former ‘lifestyle’ would suggest that I got.”

In the absence of God, Hitchens focuses on the bodily impact of his cancer, fixating on the agonizing loss of everything that makes him human—his weight, his hair, his sex drive, his voice. He describes the injections to reduce pain in his extremities, which end up going numb entirely. The cancer is not part of his body; he repeatedly calls it a “blind, emotionless alien,” a foreign enemy that he refuses to acknowledge as something he created.

Rakoff, like Hitchens, parses the physical losses that come with his cancer, the indignities and the pain, but he laments the betrayal of his body rather than outsourcing the problem. The most devastating news he receives with his diagnosis is that his arm and shoulder will likely have to be amputated. In preparation (and in true defensive pessimist form), he starts living his life without it, learning to type, cook, and get dressed without an arm. Mostly, though, he’s distressed by the aesthetics of the amputation. It’s a wondrously shallow and intensely honest preoccupation: “I imagine that the rest of my life I will see the tiniest involuntary flinching on the faces of people as they react with an immediate and preconscious disgust at the asymmetry of my silhouette.” He eventually learns that the arm won’t need to be amputated, but on a recent episode of This American Life, Rakoff revealed that he had lost the use of the arm during treatment. There it hung, already dead, a preview of what was to come.

Both writers dispense with the notion of the grace of God, or of making peace with death. As they lose their bodies, they furiously record the insecurities, complaints, and gripes that come with cancer—they refuse to dignify it as anything more than a bitchy, demanding houseguest. Rakoff, as he’s being treated, says he wants to “get on with the business of one’s life”; he and Hitchens find meaning in the petty frivolities of life as it is being wrested away from them. In doing so, they’re able to live until their last moments and face death in character: Hitchens with defiant bravado, and Rakoff with disciplined resignation.