Recently, I interviewed Joe Boyd. If you’ve never heard of Joe Boyd, you’ll have to excuse the lackluster introduction; if you have, chances are you’re thinking “wow, neato,” or at least “Joe Boyd, eh? What’s he got going on now?” (The answer is nothing earth shattering—he was in town to produce a show in honour of Kate McGarrigle, I happened to get his contact, and he kindly agreed to an interview.)

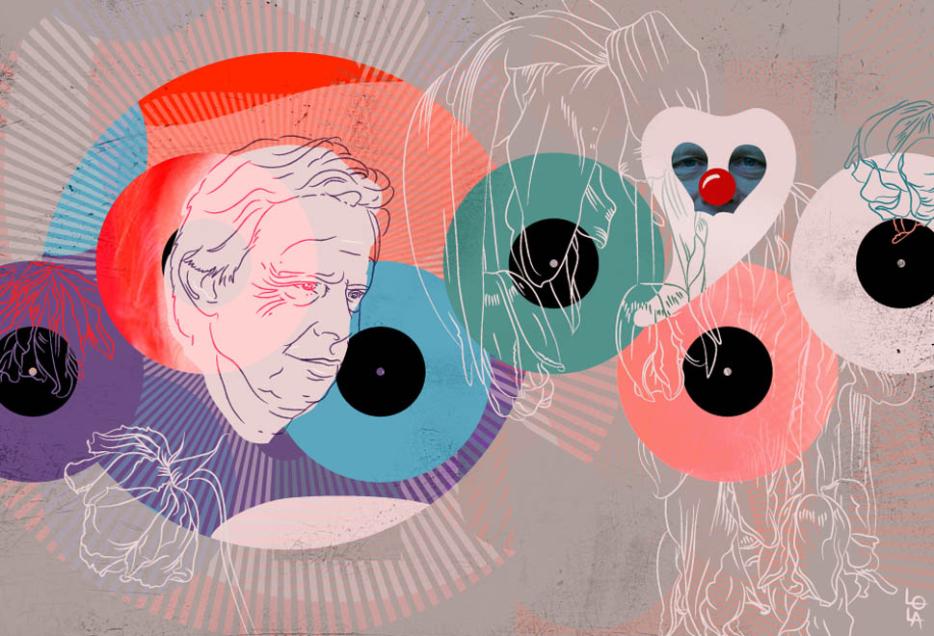

For most of his life, Joe Boyd has been a professional Significant Figure in Music. In 1964, fresh out of Harvard, he managed a UK tour for the Blues and Gospel Caravan, featuring Muddy Waters and Sister Rosetta Tharpe; as a stage manager at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, he witnessed Bob Dylan plugging in. After moving to London, he discovered and produced albums for Fairport Convention, the Incredible String Band, and Nick Drake, as well as Vashti Bunyan (whose Just Another Diamond Day sold a few hundred copies upon its release in 1970, then a few hundred thousand more following its reissue in 2000, when Devendra Banhart croaked his approval). Then he went to Hollywood, where he worked on the Clockwork Orange and Deliverance soundtracks; THEN he produced Richard Thompson, Toots and the Maytals, Mary Margaret O’Hara, and Kate and Anna McGarrigle, among many others, while running his own label, Hannibal Records, and helping to launch world music. He is the Cigarette Smoking Man of 20th Century tunes.

Joe Boyd made some of my favourite albums of all time and worked with people I absolutely idolize, so I was over the moon to meet him. And the interview went fine. It was a normal interview. He seemed like a normal, abnormally accomplished 64-year-old man. As I walked out of the Sheraton Centre, I wished our paths had never crossed.

I’ve been a music fan my whole life, and I’ve managed to maintain a comfortable distance from the universe of music-making: I’ve never worked in the music industry and I very happily possess little music ability, which makes it easy for me to mythologize the artists I love most. Even the most wonderful, inhumanly talented writers in history, I’m wondering how they did it; musicians, I don’t want to know. As far as I’m concerned, they did it cuz they were magic.

People are people and, as people, we’re all squirming in a pile on the same buggy mattress. But music isn’t of the buggy mattress, and my favourite musicians are not people to me. Not gods, necessarily, but more like saints—their characters are fixed. They don’t stub their toes or take out the garbage or go to the bathroom, unless going to the bathroom is a condition of their sainthood. To be snubbed by Elton John, or to meet Elton John and discover he had bad breath, would be like meeting a ghost who smelled like onions.

I write about music, but the musicians I’ve written about haven’t established their mythologies yet. They are still around and doing stuff, making flawed work and getting better (or worse). No matter how good their songs are, I can’t lose myself in them because my job is to see the makers as human beings. That’s probably why my favourite music—my “me time” music—is old and irrelevant.

The saint-like musicians I venerate are mostly dead, or at least very remote; as such, I do not write about them. My favourite albums occupy a little bubble in history that begins and ends with the album; they were created in different worlds. I’m sure life in that world contained its share of drudgery. The players probably shat, drank tap water, rubbed their feet on the carpet and got shocks when they touched their instruments. But I wasn’t there, I can only imagine what it was like, and that’s what this is about—my imagination.

Joe Boyd specialized in these kinds of albums. He was a fine musicologist—he could slip into a subculture and pinpoint its musicians laureate—with an excellent ear for character. His most triumphant discoveries were as idiosyncratic as they were musical, and as a producer, Boyd was more an impresario than a stylist. He got everything cued up and then—as Thompson once recalled in the Telegraph—read the newspaper behind the dials. Joe Boyd was the freak whisperer.

He discovered Nick Drake through Ashley Hutchings, the bass player for Fairport Convention, and produced his discography, saw his albums flop in the marketplace as Drake refused to tour or do interviews, watched him fade out of life and overdose on antidepressants at age 26. In his book White Bicycles, Boyd describes Drake as a strikingly handsome but cripplingly shy young man with dirty fingernails, who talked in stutters and coughs. And yet Drake had a voice like smoked wood, and his phrasing was oracular. Even when he was alive, it seemed, he existed most authentically in his own myth.

Looking at the outer sleeve of Unhalfbricking, I feel the same way about the members of Fairport Convention as I once did about the kids from Goonies, or the characters in Archie comics (Sandy Denny is Archie Andrews; Richard Thompson is Jughead Jones). They never existed but they still exist, and they will always exist, in a parallel world where Peter Pan and the Greek Pantheon and Tony the Tiger are still doing their things. Where the “they” in “they say…” live. At rare points in history—say, on the outer isles of Scotland in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s—that world has overlapped with ours. Vashti Bunyan and the Incredible String Band were there for it, and they left records of how idyllic and improbable their lives were.

I left our interview with a sense of horror that a guy so guyish, so clearly rolled out of human dough, had swapped skin cells with these lovely specters—and then swapped skin cells with me, in a brief handshake at a metal table outside a Starbucks. A closed Starbucks. In a crowded hotel lobby with the acoustics of a swimming pool. The interview had gone fine, but it hadn’t been worth the stars in my eyes. I texted friends, ones I’d texted beforehand and who’d texted back with questions to ask—music trivia, facts they needed for complete sets—saying I wished I hadn’t done it.

But enough time has passed now that I can’t immediately recall what he looked like, or how uncomfortable the plastic chair felt underneath me, or the sting when he spoke brusquely or my annoyance when he rescheduled the night before and again in the morning. The tangible Joe Boyd has sunk into my mnemonic junk drawer of mundane encounters. And the other Joe Boyd, all lousy with the skin cells of giants, is the one I’m thinking about.