There was a plane crash—that’s the kind of line I’d like to open this with but there was no plane crash, just me wishing there would be one. I was going to a country with no words. Or the words were there but I didn’t know them. Without words, it was as if I was getting born. Except I had already been alive for 15 years. I wanted to die.

We landed in Toronto, lined up with other gray-faced newcomers (Welcome to Canada the signs read), got our lives stamped under bile-green lights, moved forward, got spat out of sliding doors right at my father waiting behind the red rope. Then we drove through an endless slab of asphalt—the sea-wide highways—in my father’s Buick. Then we were here: Hiawatha Street. Hiawatha, I repeated and repeated, testing, tasting the rhythm of the new word.

Our apartment was white and clean. There was a plastic patio set in my parents’ bedroom/living/dinning room. A hole in the middle of the table. No umbrella. My sister and I shared a room, the beds without mattresses just the box spring. Exhausted, our skin humming from the flight, we slept hard. That week, my father lost his good job. He was now powdering donuts at night at Tim Hortons.

From the start, the family was tense about being here. Grieving wordlessly—even though we spoke the same language. Someone was due to snap, yell: Let’s go the fuck back! But no one did. I missed my grandmother the most. (There is forever a roller-coaster drop in my chest when I think of her.)

I tried to assimilate. Six months into my ESL class, I challenged myself to write a short story in English. I sat with my dictionary and carved out words, those words rock-heavy as I lugged them up the slippery hill where I tried to build my story. It was a grotesque monster: the smaller rocks underneath the big ones, the construction absurd, falling apart. I didn’t know the language.

Mute, I felt mentally ill from loneliness. I woke up with it and fell asleep to its insistent drone. I observed my schoolmates, Canadian girls. I tried to learn which ones were losers and which ones were cool. Those were new words although I knew their meaning in Polish, too. There were other words: popular, slut. There were girls with dead eyes, coral lipstick, teased-up hair like halos, there were girls with pink hair and boys’ clothes intentionally. Slut and popular, respectively.

There were other girls but you needed a key to all of them: language. Language was necessary to be a girl here because girls talked. Once, Nasty Nancy said to go back to my country. I understood that, agreed. Slow Sarah was friendly though. But she was a loser and I didn’t want to be seen with her. And then she’d ask me to repeat what I had tried to say anyway. And she would say, like everyone else: Do you like it in Canada? As if they all invited me here.

Fuck you.

I moved out of talking. Now I lived in a library. I started reading. English books from the YA section. They had large fonts, easy words. Christopher Pike: Gimme a Kiss, Fall into Darkness, Die Softly, Burry Me Deep. In Polish, it was On the Road, Lolita, 1984, Justine. In English I was 10. In Polish I was 17. The first book I read in both languages was Anne of Green Gables—I loved it as a child and now as a teenager I could orient myself around it because I knew the story. Two different languages to make sense out of one.

This is how it was: two different languages, two different lives. In Poland, during summers, I played with words, played with boys, boys playing back, all of us smoking in dives, talking about Witkacy and Gombrowicz. In Canada, I couldn’t recite a joke I rehearsed a hundred times. On Wednesdays I waited for this guy in front of a club where he worked as a busboy. He would take me upstairs to his crummy hotel room. I was weird, he said, because I never talked. Fuck that guy. But I dreamed of the time when I could tell him a joke. Without that joke I was just a Wednesday girl.

It was like that for many more years. Every year it was better but it was never so fluent that I could float. I was in a flatline of blackouts for the majority of my twenties, but when I wasn’t, I absorbed words. Maybe I absorbed them soaked in alcohol with bar shitfriends when I wasn’t paying attention.

With words, came people. Real friends. Lovers. Experiences. Jokes. Humour had big loud elbows and was elbowing itself into crowds of hugs. I never hugged in Poland, but here everyone hugged so, fine: hugs! Hugs! And I apologized. To people stepping on my toes, bumping into me, I apologized for coughing, for apologizing. Fine, I’m sorry! I’m sorry!

I was assimilating.

Furthermore: I read The Handmaid’s Tale. I did an independent study project on Robertson Davies. I re-read Lolita and 1984 in English. I stopped reading Polish. In English, I was becoming fluent; I was floating. I learned what it meant to live in subsidized housing and how that was exotic to those who never had to. Write about that, people said.

So here I am, writing about it. Because I eventually started writing, too. Then I was fully assimilated. Then once I was assimilated, I started loving it here. And I got sober here. In English. (The meetings were in English). And I had a kid here. And then it was my home. And now here I am.

Sometimes I stumble over a word when speaking or writing. When I see it but can’t name it. The words get mixed up in a pile at the bottom of my heart; they come up Polish when they should be English. They show up in a line of easy stock phrases when the desire is to dress them up in couture. They are missing articles or they have extra articles. I will never fully understand articles. The same space where those live in an English brain, in mine is probably crammed up with ą, ć, ę, ł, ń, ó, ś, ź and ż. Useless letters until I read a Polish book.

I started reading Polish books again. It had been a while. Years. But lately, I’ve been able to get books by tapping a finger on a square of glass. I read books on my iPod. iBooks. This is how I returned to Polish. There is a Polish app with Polish books so I picked three authors to start: Manuela Gretkowska, Michał Wiśniewski, Dorota Masłowska. Their words are brave, playful. They write how I think now as a writer, in the language that I used to think in. I will probably never write in it. I miss it. Like a love long gone. I’m writing about it in English, about my first love. It’s always here. An undercurrent of the river I’m floating in.

--

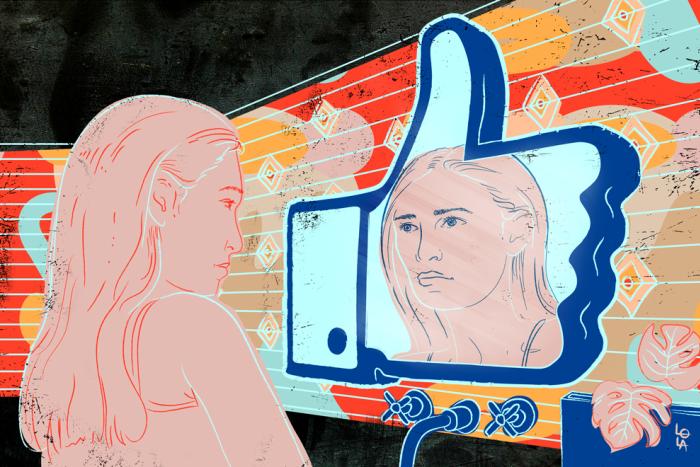

Photo by Jowita Bydlowska