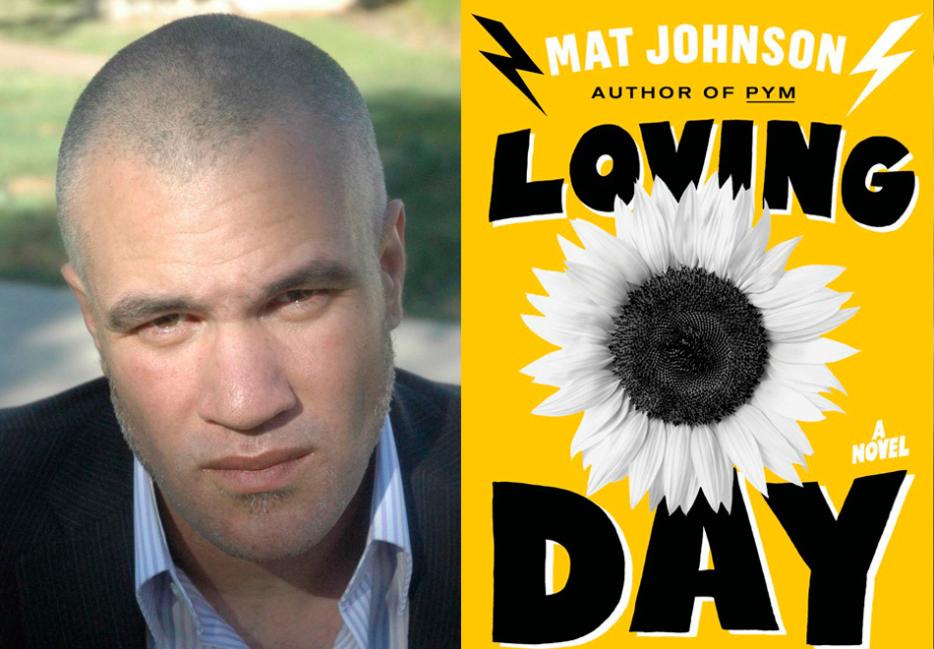

Mat Johnson’s 2011 novel Pym, which blended references to Edgar Allan Poe’s lone novel, polar adventures, commentaries on race, and academic comedy, brought deserved attention to its author. Johnson’s first novel had been published a more than a decade earlier, and the breadth of his work since has expanded past fiction and into historical reporting and comics. His new novel, Loving Day, seems to represent something of a fusion of his interests: Warren Duffy, the book’s narrator, is a comics artist himself; as the book opens, he has returned to Philadelphia after the end of his marriage to a Welsh woman. There, he finds himself enmeshed in familial questions old (the inheritance of his father’s mansion, “decaying to gray pulp,” as Warren puts it) and new (the discovery that he had fathered a daughter years before). This is not, however, an entirely realistic novel. That mansion? Haunted—albeit in a low-key way.

Loving Day allows Johnson plenty of angles to explore a host of complex dynamics, from Warren’s fraught relationship with his own past to the questions of race that nearly every character in the book wrestles with. (This is something Johnson has written about in nonfiction as well.) In a recent interview with Victor LaValle, Johnson said, “Slowly, as an adult, I started growing warm to mixed identity, as being a healthier way of self-definition.”

I spoke with Johnson recently, reaching him over the phone in the city he now calls home, Houston, our conversation ranging from his work in comics to bridging the gulf between writing that entertains and writing that’s artistically dynamic. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

*

The main character of Loving Day creates comics, and you’ve done several graphic novels. Were you drawing from your own experiences here? I’m thinking particularly of the scenes with Warren at the convention early in the novel.

You know what? Nothing in the whole book happened. Or at least nothing happened in any way that it plays out there, for the most part. It’s funny—when I was writing, I wasn’t thinking about that part, the comics part, as being autobiographical, because in the comic book-world I write the stories and the artist does the art. So in my little view of the world I thought, “Yeah, it’s the opposite. Instead of writing the story, he draws the stories.” But that’s just what my tiny little worldview looked like.

When I was 16, I had this pregnancy scare and my whole life changed at that point. And part of the book was looking back at that point and saying, what if things had been different? So the product of that was here’s a story that’s entirely different from my actual life, but it’s also this alternate version of myself—it’s autobiographical without anything actually happening there. Some of the race questions were the same, but the actual physical events, no, I didn’t inherit a haunted house or join a mulatto hippie commune. That’s just in the book.

Is that something that you often do in your fiction—take a situation from your own life and then imagine a version where things went differently?

No, that was the first time I’d done it. My work’s been all over the place: I’ve done literary fiction; I’ve done non-fiction; I’ve done comic books. I’m usually trying to do something completely different every time. Not out of any artistic push, but just because I get bored, you know? So the next project—the more different the next project is from the last one, the more excited I get about it.

And I think with this one, the nature of this identity thing that I was dealing with, I had to do it directly—I had to treat this thing like I was going to lay myself on the table and chop myself up into little pieces and serve that like sashimi. That was the goal. And the only way I could get into it with the full intensity was to take as much as I could from my own life.

But writing in general sometimes is like a dream. You might recognize things from your life and there are pieces of yourself in there, but everything is twisted around and different. People act like they interact in the real world and places are changed, but that product can still only come out of you.

I read Pym a couple of years ago, and when I first looked at the summary of this, I thought, “Oh, there are ghosts—this will probably be similar in tone.” And after reading it, that’s not the case: there’s a similar sensibility, but they’re very different books.

Yeah. Pym is more of a direct intellectual satire, and it’s also kind of a hybrid of everything between a literary essay and fantasy book. That was fun because I hadn’t done it before. And this one is more, despite the ghosts and despite the moments of high comedy, it’s more of a realist book. The funny thing is, I just don’t really care that much about realism. I want it to be real, but my primary concern is emotional realism. So if some crazy stuff happens, I don’t mind as long as it’s feeding some larger truth. And I think for me these elements that turn things upside-down are helpful in breaking through the moment and trying to get to something that’s underneath.

What’s the process of finding the balance between the comedy and the realism and the emotional truth like for you?

Well, you write for 20 years, slowly you learn how to do things. For me, comedy is my first response to everything. Even my kids are like, “It’s not funny, daddy. Just shut up.” So that part comes naturally, and that part, often, I’m not even trying to do it—it’s just coming because that’s how I’m dealing with the world.

But yeah, there’s the balance. And something I’ve been looking for, and I watched out for with this book, is if you get too silly, you lose your emotional bearings and it becomes cartoonish. And once it becomes cartoonish, nobody can really get hurt. You know, the anvil drops on Wile E. Coyote and the next day he’s walking around again. So when another anvil drops on him, we laugh but we don’t really care because we know he’s going to be okay, you know? Because it’s a cartoon.

I was thinking a lot with this one about how I could have moments of absurdity but not have them become so unraveled that we cease to care about characters. With a lot of pieces, you create a reality for that story—and within the reality of this story, this is possible and this is not possible, and this can go this far and it can’t go this far. And I think the reality for this story was largely based around this father and this daughter. You know, within their reality things could move a little beyond what we’re used to but it couldn’t go too far because if it went too far it would’ve become something dramatically different.

The surreal elements felt like the kind of story you might hear someone tell in the bar: “Oh, this one day I saw this one thing that doesn’t really have an explanation.”

Yeah, that’s exactly it, right? We already live in a reality where people claim to see stuff like this. And you know there are TV shows and books where people actually claim, completely soberly, to see ghosts. Well, we don’t live in a reality where the ghosts open up a bar down at the corner and everyone goes to the ghost bar—all of a sudden that is beyond what we’re doing, right? So to just have this guy seeing ghosts, to have others see them, or having even a video of ghosts, that’s all within our reality. It’s on the far end of where we are, but there are people who are basically sane people who claim that. So that gives you the space to play with that. But if you take it past that, it moves out of our space.

But a lot of times, the more you write, the more you start to understand what the book’s about, and then you start tweaking it in that direction. And the more you tweak, the more this calculation changes and it becomes more and more specific. I started this book in 2007—I wrote the first 100 pages in 2007 and 2008, and then I went away from it for three years, picked it back up in ’11, right after I did Pym, and then I wrote it for another three years. But most of it was done within an actual year-and-a-half writing space. That was the main manuscript.

And then most of the work after that, besides polishing, was reduction. This book was actually about 175 pages longer, and one of the things I’ve been really trying to do is create literary fiction that also moves quickly. There’s something I look for on the page, and it’s something that’s not always valued in literary fiction, but I really like to have things move. So I gutted down entire chapters in the book. In the early versions of the book it went for another 100 pages and there were another 75 pages inside that we cut out—once we got to that point, we realized it was over and that you have to whittle it down from there. But my best writing is my rewriting, you know? My first version, in my head, it’s just the marble that you’d start with, and then I’m etching it down from that point.

In an interview you did with Victor LaValle, you talked a lot about George R.R. Martin and Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. Do you read much fantasy and science fiction?

In a way it isn’t that much, but when I talk to Vic we just tend to geek out, you know? So I get that. During the school year I’m reading mostly literary fiction. I’m reading my students’ literary fiction and I’m reading literary fiction on my own and stuff to teach them. So when I get a break I love just reading fantasy and science fiction. It’s not to say they’re smarter, but they’re concept pieces as opposed to prose-based pieces or character-based pieces, so they’re easy to consume—you’re not focusing as much on the details as you are on the larger picture of what’s being done.

And the other thing, I really like looking at fantasy. Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is a great example. I want to write compelling, interesting books. That’s my goal. I’m not writing just to tell the world I’m a genius. I want to tell a fun story. My idea of a perfect book is a book that on one hand is smart and engaging and does something new and makes you look at the world or writing itself differently, but it also has to be incredibly entertaining. And if you’re not doing both of those things for me, then it’s not working.

I see a lot of smart fiction from my students. It’s very smart, but it’s not engaging. So I’m constantly working with them to try to get them to have both of these aspects. I think at some point in the 20th century there was a dividing line where we said, “Okay, entertaining writing over here and artistic writing over there.” I just think that’s a horrible idea. Because part of what we’re doing is entertaining.

Now, if you can entertain and also do other impressive, interesting, artistic things, that to me is the next level. So I read some books just because of the artistry, and I read other books because I’m primarily interested in the entertainment. And some of them, it’s both, and you don’t even expect it. Like Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, I read that one for a fun fantasy, but it’s a beautifully written book that really explores these themes and these contradictions, and it can teach you a lot about writing.

The other thing I’ve been doing for years is when all my students tell me, “We’re all reading this book. I love this book. We’re reading this book,” I’ll go read the books. And my students have been telling me for years, “Game of Thrones, Game of Thrones.” And I basically didn’t listen to them until the TV show started and I enjoyed the TV show. So last summer I read all the Song of Ice and Fire books. The basic part is, what are they connecting with? What’s going on here that has them captivated? As a writer who wants to captivate people, I want to know—I’m not raising my nose at it. And I’m glad I didn’t, because he’s a brilliant writer. People look at someone like George R.R. Martin and think oh, it’s just genre. Listen, there are 10,000 people trying to write Dungeons and Dragons stories and nobody is nearly as good as he is. It’s a lot more complicated than that.

Could you ever see yourself writing something that far into the realm of the fantastical?

I can, I just don’t think I’ll ever be able to. The fucked-up thing is I think you don’t get to be the writer you want to be. You end up being the writer that you are. And the goal is to become the best version of the writer that you actually are. I would not mind doing [fantasy] at all, but every time I come in on a story, and I’m thinking about just entertainment, all of a sudden these larger ideas start becoming really interesting to me.

And then it ends up being this sort of conversation between the ideas and the storylines. Pym, I just started and thought, “I’m going to write a story about monsters underneath the ice.” And then it turns into this intellectual grappling with Poe’s Pym and the idea of literary lightness. But I didn’t intend that; I just wanted to have a story with snow monkeys. But if I had just said, “No, no, I’m just keeping the snow monkeys,” it wouldn’t have been a particularly interesting book. So the only way I can be at my best is to do everything that I have the power to do as opposed to limiting it to a pre-conceived notion.

Your new novel opens with the image of a mansion in the middle of Philadelphia, which felt jarring to someone in a city where there isn’t that kind of sprawling space around.

That’s what my neighborhood was like growing up. That’s Germantown. There were these big mansions and sometimes there’d be 12 people living in this lower mansion and it turned into an apartment building or something. They were all around us.

And the mansion in the book is a real place. I didn’t even change the name; if you Google “Loudoun Mansion” you’ll see pictures of it. And, to mind, it’s exactly the way I described it. When I started the book I’d already written the description and I created the story of a fire that had burned it down, and then I went and looked up the mansion just to get an image of it again, and it turned out a fire had burned the roof and it was closed down. Maybe I knew that, but I don’t think I did. It was one of those creepy things.

Philly’s such a different beast from New York and Manhattan because it’s more spread out, a different history—at one point a wealthier, bigger city than New York was, so you see the leftovers of that wealth.

You’re in Houston now. How do you find those two cities compare to one another?

Oh, they’re almost exact opposites. And I love Houston. But in Philly, I mean, just look at the architecture. Philly is about history, and you have a style of building, it doesn’t matter if it was built in the 1700s, it’ll still be around today. In Houston, a building looks at you wrong and it gets razed and a new building is there the next day. So we have in Philly this concept of selfness—it’s so based on the history and the history of America and the past in a lot of ways. And in Houston, everything is about the future and what’s going to be happening next. And because of that, too, it has a ton of immigrants coming here, compared to Philly, which is actually shrinking because it’s not taking enough immigrants in anymore.

Do you find that Houston’s had any effect on your writing?

Usually there’s a delay—I think you’re going to see the effect of Houston on my writing in my next book and the book after, because I think it takes me a while to gestate what’s around. But yeah, one of the cool things about Houston, it’s like a crossroads between Austin and New Orleans and Dallas and San Antonio—it’s this merging of all these different cities, and there are so many Houstons here.

I love it because they put a ton of money into the arts—they have a ton of money, so the arts here, there’s a disproportionate investment. Visual arts, opera, ballet, classical music, and the writing program that I teach at all have far more money than they would anywhere else. It’s kind of like a Mecca for me. And I enjoy my university, too, because I have an incredibly diverse university. It’s one of the most diverse universities in the country every year. So I get to teach people from all different backgrounds. And as somebody who never really quite fit in anywhere, I love being in the place where nobody’s fitting in and all different types of people are there.

Since it came out, Loving Day has been getting a lot of attention for the way that it addresses questions of race and racial identity. This year, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout and Nell Zink’s Mislaid have also been similarly acclaimed. Do you think, because of where we are in our society right now, we’re going to see novels that are asking these bigger questions more well-received and more discussed?

I don’t know. That’s a good question. I think part of it is coincidence, because Paul Beatty is a great writer and Paul Beatty just happened to have a book this year. You know what I mean? And also I think you’re seeing somebody whereThe White Boy Shuffle was out there and people immediately know about it. So I think any time that happens it’s going to be sort of an event.

With myself, I think it’s also kind of a question. I don’t know Nell Zink. I haven’t read her book yet. It sounds interesting, but I haven’t read it. But with myself the thing is, the first ten years of my writing career, I couldn’t really even get reviewed. My first novel came out in 2000 and I didn’t get a review for a novel in The New York Times until 2011. And one of the big differences there was Twitter. I was on Twitter. People saw what I was saying. They saw the humor, so they gave the book a chance, and all of a sudden I started building more of an audience.

So that’s part of it. But this other question of identity? I think if you pull back and you look at why the book’s out in general, there’s still the same question of identity. It tends to get noticed when it’s not a white male author. [Jonathan] Lethem’s last novel, which I really enjoyed, is a question of identity. But it’s the question of Jewish and Communist identity. With Michael Chabon’s last book, Telegraph Avenue, it was a question of identity and place like mine was, but it was more of a multicultural view, and it was looking at Berkeley.

I think the idea of identity and the idea of place are things that you’re seeing almost constantly. The other part is how we’re framing them. But if there’s a bandwagon, I’m just happy for the good timing. I’ve got to tell you, I’ve been underexposed and overexposed, and I definitely prefer the latter. I know what it’s like to have a book come out and nobody’s reviewing it—it’s not in the bookstores, you worked on it for years, and you’re just unbelievably frustrated.

I remember my second novel, I couldn’t see it in any of the stores and I didn’t get major newspaper reviews on it, and I remember just feeling like I had lifted this boulder and dropped it in a lake and it disappeared without a ripple. I had this image of that. And I was thinking, God, is this worth it at all? So to go from that point to getting reviews and getting smarter interview questions—I mean, even having interview questions with somebody who’s actually opened the book at all is amazing. I used to get interview questions like, “Oh, so you wrote a book? What’s it about? Oh, okay. That sounds interesting.” I’m just really appreciative right now. I’m just going to try to enjoy every second of this book.

Do you see yourself doing more comics work in the future? Are there other stories you want to tell in that medium?

Definitely, I really want to. Collaborating … I love novels, and the novel is my primary form, but it’s utterly and completely solitary. The idea of actually getting to do a group effort, and wake up in the morning and get new images in the mail from something I worked on, definitely I’d like to do that again. But we’ll see what happens. I keep telling my wife my retirement is just going to be working on a couple comic books. That’ll be it.

It’s funny–I first became aware of your fiction through your comics work, when I saw a review of your graphic novel Incognegro.

I’m so glad that happened. It’s funny because at first that didn’t really happen. There wasn’t really much crossover. But you know what’s weird? I think I actually owe a lot to illegal downloads, because once my comics were out there, people were downloading them, and probably only one in five were actually paying for it—the rest were getting them for free. And it was a great way to get your work out there. I’m sorry to Time Warner and DC Comics for not getting that money, but oddly enough, it worked out great for me.