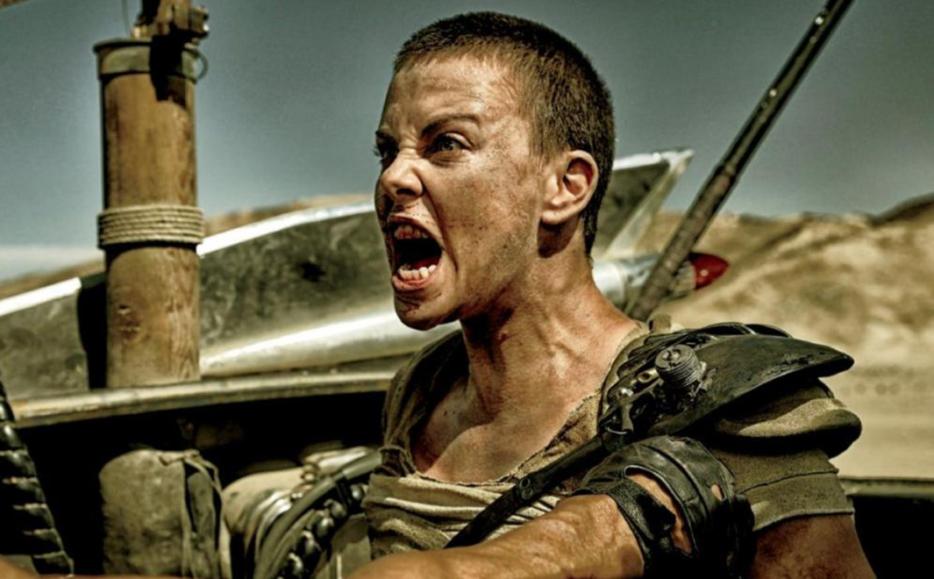

Like every woman I know, I came out of the theater after seeing Mad Max: Fury Road prepared to swear eternal fealty to Imperator Furiosa. The character spends most of the movie behind the wheel of a massive truck, splatting skinhead-esque pursuers as she ferries five abused women to safety. Even if she looked like Tom Hardy instead of Charlize Theron, I still would have left breathless.

But Furiosa isn't just a kickass action hero. She’s something more important, and for me, more resonant: the latest, and one of the best, in a line of women I've been following doggedly since childhood, across hundreds of years of literary history. She is a warrior woman, and she's the only kind of woman who makes me think there's a place in femininity for me.

*

Fury Road has been lauded as a feminist movie, but it's not: it's simply an exceptionally good action movie that isn't antifeminist. There's nothing especially ideological about Fury Road; even the wives' refrain of “We are not things,” subversive as it may be in the action film sphere, should in a better world be about as revolutionary as “one person, one vote.” What's striking is not how radical it is, but how oddly rare it is for a movie to acknowledge something fundamentally mundane: there is more than one way to be a woman.

In a few lean lines (the script is stripped of almost all expository fat), the movie shows us more types of women than all of the previous Mad Max films combined. The wives, though scantily costumed and indeed, very beautiful, are not monolithic: there's the loopy dreamer The Dag who wants to plant new seeds, the calm and curious Capable who wants to comfort others, the stoic Splendid Angharad who doesn't back down, the frightened Cheedo the Fragile who wants to go home and make the best of the hand she was dealt, and Toast the Knowing, too difficult to sum up in a single sentence. In this world, women even get to age. The elderly biker gang, evocatively called the Vuvalini, is no less inspiringly badass for being old.

And then, there's Furiosa.

A lot of different women—different ages, different colors, different personalities and coping mechanisms—can see themselves reflected in Fury Road. (We'll have to wait for different sizes; Hollywood isn't quite there yet.) But Furiosa in particular is the figure many of us have been waiting for. She manages to be the quintessential male action hero: bold, self-sacrificing, grease-smudged, practically dressed, violent as needed, nobody's love interest, and willing to fight uncompromisingly to protect those who need her help. She just happens to do all this while being a woman—and in doing so, reminds us that none of these “masculine” qualities actually require a man.

For me, the phrase “strong female character” now brings to mind the comic series by Kate Beaton, Carly Monardo, and Meredith Gran. Their busty ladies—Georgia O'Queefe, Susan B. Assthony, and Queen Elizatits—lampoon the cultural cop-out of the token Badass Woman, a male-gaze-approved (and male-gaze-approval-seeking) hot chick who gets to kick a carefully rationed amount of butt, provided the boys like to watch her do it. But the warrior woman isn't a Strong Female Character. She's not a variation on conventional femininity, a Barbie who stole G.I. Joe's gun. She's not a tomboy, either, deliberately rejecting conventional femininity in favor of macho pursuits. She just doesn't actually give a shit about conventional femininity. Because what she knows is what Furiosa knows, and what it took me decades to learn: that both “feminine” and “macho” are consensual fictions, designed to keep both women and men in their place. Designed, in fact, to cover up the fact that women's place is everywhere.

*

When I was a kid, I thought I didn't know how to be a girl. I was a chubby, uncoordinated, oafish child, too moody to be docile or sweet even though I knew I was supposed to be. Girls in the stories I loved were often passive, if they were present at all; they had a kind of delicacy that just wasn't available to an oversized kid with an oversized sense of injustice.

Only a cherished few books had female protagonists, and they were often good-natured or talented or pretty or embodied some other kind of acceptable femininity that made me feel even worse. (Looking at you, Sara Crewe.) I never thought of myself as boyish, or even as a tomboy; tomboys, in the novels at least, excelled so much at toughness and athleticism that they saw traditionally feminine pursuits as being beneath them. They weren't beneath me—they were way over my head. I wanted to get better at being a girl, but I thought I didn't know how.

More than that, though, I wanted a different goal. I'd been obsessed since nursery school with the Knights of the Round Table; I loved their loyalty, their purpose, the way they responded to injustice by (sometimes quite literally) slicing heads first and asking questions later. For knights, the delicate damsels weren't role models; they were responsibilities, because the fragile must be protected. Why couldn't I be stalwart and gallant, a shield for the weak, a wielder of enchanted swords, a fetcher of ladies out of boiling baths, pure of heart enough to see the Grail? Lancelot was ugly, and it made him the world's best knight.

Because what she knows is what Furiosa knows, and what it took me decades to learn: that both “feminine” and “macho” are consensual fictions, designed to keep both women and men in their place. Designed, in fact, to cover up the fact that women's place is everywhere.

The closest I got was Alanna. The main character of Tamora Pierce's Song of the Lioness series, Alanna disguises herself as a boy and trains as a knight. She needs to pass as male to trick people out of underestimating her, to make sure she'll be judged by her stoicism and ferocity, instead of her utter failure to be ladylike. But it's a survival tactic, and once it's too late for anyone to stop her, she makes it clear that she's always been a woman—stoicism and ferocity are not, in fact, the sole province of boys. Eventually, she's known as “The Woman Who Rides Like a Man,” embracing everything her female identity allows her, if she wants it, while also holding fast to the things it's supposed to deny.

I ate these books up. I was nine years old, and still engaged full-time in the project of being a terrible girl on every typical parameter. I was mercurial and argumentative and involute and never dressed properly. But sometimes there was a tiny glimmer: could I just learn to ride like a man? And what did “like a man” mean, anyway? I didn't exactly want to be a boy, after all—I just wanted it not to matter. Could I learn to ride, and fight, and dress like myself, to reach out and take the things I wanted, whether I was supposed to have them or not?

*

There have probably been more real-life woman warriors than we know. Until recently, archaeologists would determine the gender of a grave's occupant based on the artifacts buried within; jewelry meant a woman, weapons meant a man. When skeletons are actually sexed (an imprecise process, often, but better than guesswork based on accessories), there turns out to be a small but existent number of women interred with weaponry.

Even then, some archaeologists—I'm willing to bet male archaeologists—are quick to caution that just because a woman was buried with weapons doesn't mean she wielded them. Arms and armor in a man's grave are martial, but in a woman's grave, they're symbolic. When the body of an Etruscan prince was unearthed in Italy in 2013, he was initially assumed to be a great warrior because his skeleton held a lance. The incinerated corpse on a smaller platform was thought to be his wife. Once it was determined that the prince was actually a princess, though, the lance magically became a metaphor for marriage according to a (male) researcher: “The lance, in all probability, was put there as a symbol of the union between the deceased.”

The lance could have been a symbol of power. It could even have been a symbol of war, the way it would be in the hand of a real-life Furiosa: an Amazon, for instance, or Boudica, the British queen who led a revolt against occupying Roman forces in around 60 A.D. But no, that's not what women do; that's not what women have. An unidentified skeleton with a weapon is a man; an unidentified woman with a weapon does not really have a weapon but rather, a very long, sharp wedding ring.

*

Furiosa, though maybe our most recent example, certainly isn’t fiction's first woman warrior. Neither is Alanna. Girls like me, I learned as I got older, have been around for hundreds of years. In Edmund Spenser's epic 16th-century poem The Faerie Queene, for instance, the female warrior figure is Britomart, the Knight of Chastity. It sounds “girly” but it isn't: she’s a “martial maid.”

Each volume of The Faerie Queene focuses on a particular virtue, and a knight who serves as its human embodiment. Britomart is the hero of Book III, the book of Chastity, which for Spenser means not celibacy but faithful love and, by extension, ideal womanliness. (Even in a country ruled by a Virgin Queen, “perfect woman” and “perfect wife” were often coextensive.) His female characters react to love in different ways: by running from it, by demanding it, by clinging to it as a comfort while being victimized. Malecasta requires all knights to cast off their lady-loves and pledge fealty (and sex) to her alone. Florimell flees from everyone. Amoret, hounded by men who seek to rape or otherwise use her, becomes so committed to her lover Scudamore that, once reunited, they are compared to a single hermaphroditic creature. In trying to escape exploitation, ironically, she loses her identity.

And Britomart, arrayed in armor and furnished with a magic spear, fights her way through the book like a man might do. She is described as being “full of amiable grace / with manly terrour mixed therewithal.” She’s appealing, but intimidating, specifically in the manner of a man. But Britomart, when she rides out in armor, is not cross-dressing, passing for male, or even inhabiting a genderless space. She is interacting with her female identity—with love and fidelity, which are women's qualities to Spenser but also human concerns—in a way that’s entirely different from the perfect lover or the damsel in distress.

Could I learn to ride, and fight, and dress like myself, to reach out and take the things I wanted, whether I was supposed to have them or not?

Book III of The Faerie Queene was published in 1590, and its knights-and-dragons content and deliberately archaic language evoke a Medieval fantasy; this is the era of courtly love aping the era of damsels in distress. Women in Spenser's time were often idealized into inhumanity, and in the time The Faerie Queene represents, they were prizes and bargaining chips. But it did not escape Spenser's attention that his queen and patron was a woman—that it was possible to be a woman and a ruler, a woman and a commander, a woman with the heart and stomach of a king. Britomart, one of several Faerie Queene characters who evokes Elizabeth I, lives inside this contradiction comfortably and confidently—and in doing so, shows that it's not much of a contradiction at all.

*

Britomart and I fell in love in my junior year of college. (I might have not one, but two Britomart-related tattoos.) I found her in an Elizabethan lit survey course, and on the strength of my infatuation I enrolled in an intensive five-person Faerie Queene seminar. All I did that next semester was read Faerie Queene and hit people with swords.

I started fencing around nine, the same time I was reading the Alanna books. I was never very good, and didn't compete at all until I was 18, but I came up through high school with weapon in hand. (One almost never actually calls fencing weapons “swords,” but I felt a lot of solidarity with people who wielded swords, even broadswords, which are not even a little bit the same.) Like Alanna, too, I hadn't had many female friends; I'd considered myself more akin to the boys, and a completely different species from their love interests. I dismissed girls as superficial, out of suspicion and jealousy over not being able to superficially fit in.

By college, in addition to my two weapons, I owned a little makeup and several skirts, but I hadn't stopped being rough-skinned and thick-boned, and I'd gotten into being forthright and foul-mouthed. “Even when you're wearing heels,” a friend told me, “you walk like you're wearing combat boots.” Most of the time, I was wearing combat boots. As expected, I had not grown from an ugly duckling into a swan; I had grown up to be an equally ugly duck, but with more spikes on.

Now, though, I had Britomart. And I had a sword, even if I never called it that, and my sword was not a symbol of the union between fuck-all. All this meant that being full of “manly terrour,” or wearing phantom combat boots of the soul, had lost some of the frisson of failure. Once I surrounded myself with more types of women, in books and in real life, it became clear that “girl” wasn't a script I was missing; it was a complicated piece of performance art, an interpretive dance, to be improvised at will.

Sometimes I would have liked to wear heels and still seem plausible; sometimes I would have liked to find a man and fold myself into him, or just run away from him without a fight. But I was starting to realize that being a girl all wrong, the way I did it, looked a lot like being a martial maid.

*

We are finally, haltingly starting to accept the idea that gender is not necessarily handed to you at birth. More people are publicly identifying as transgender, genderless, genderqueer—rejecting the idea that there are only two options and you're stuck with one from the get-go. It's still hard, but it's so much further from impossible than it used to be. Eventually, I hope it becomes effortless for everyone to live as the gender, or genders, or lack of gender that they know they are. But at the same time, I also hope we gradually demolish our old understandings of what gender even means.

The problem isn't just that we're shuttled into one of two locked rooms at birth, left to find our own way out if we don't belong. The problem is also that the rooms have been stocked arbitrarily with clothes and books and props and posters of unattainable ideals. The fixtures have changed a bit over the centuries, but inhabiting your assigned gender can mean accepting a host of assumptions and stereotypes about what qualifies as “masculine” and “feminine.”

Warrior women, like Furiosa and Britomart and many others, explode those assumptions. They offer one model (among many possible ones) for a form of womanhood that's not dictated by courting expectations of femininity, or conspicuously flouting them, but simply by setting them aside. The message of the martial maid is not that women have to fight. It's that fighting does not belong to men. Heroism does not belong to men. Being central to the story, acting instead of being acted upon, being something other than “beautiful enough” or “insufficiently beautiful”: these are not privileges accorded to men alone. A sword in the hands of a woman doesn't transform into a symbol of love.

I never doubted being a girl, but I thought I was missing the mark, because I thought there was a mark to miss. But there are so, so many more ways of being a woman than I realized, so many more ways than I saw reflected in the stories that spoke to me. As it turned out, one of them was mine, and I was doing it exactly right.