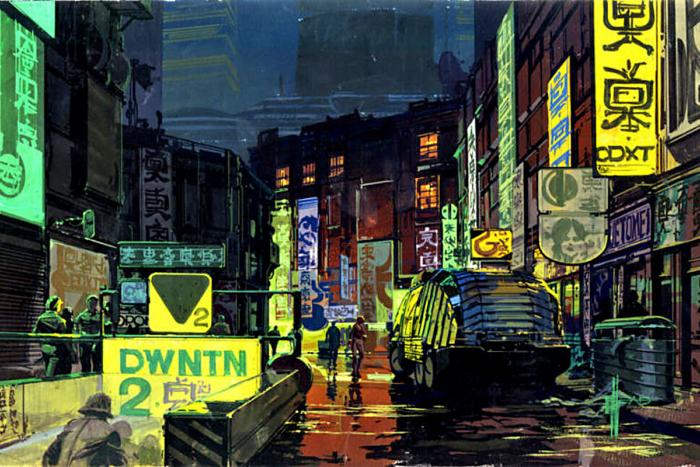

Culturally speaking, 1970s New York City looms large. Acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction have offered readers a full-scale immersion in this world. Late critic Ellen Willis’s Out of the Vinyl Deeps provided glimpses into the state of music in the ’70s. The documentary Wild Combination looked at the life and music of Arthur Russell, whose prophetic, often-unfinished work explored unknown spaces. James Wolcott’s memoir Lucking Out, which focused on his time as a struggling young critic, was released to much acclaim. Rachel Kushner’s novel The Flamethrowers told a story of Manhattan artists striving to push past existing boundaries. And Will Hermes’s Love Goes to Buildings on Fire covered five mid-’70s years in the history of music in the city, encompassing everything from Bruce Springsteen to Fania Records.11Full disclosure: I know Hermes via assorted social networks and gatherings of music writers, but that’s about as far as this piece goes into conflicts of interest. I did once knock a magnet off of Robert Christgau’s refrigerator at a music-writer gathering a friend invited me along to, but that’s about it. The jacket art came from illustrator Mark Alan Stamaty, who’d been responsible for the covers of numerous issues of the Village Voice.

That cover, a stylized map of the musical landscape of 1970s New York, is laid out with a focus on downtown Manhattan. That’s probably not a huge surprise. In Colson Whitehead’s poetic meditation on the city’s archetypes, The Colossus of New York, the penultimate section is titled “Downtown.” “This must be the place,” he writes. “It’s not. This particular street address does not exist. In another city perhaps but not this one or maybe in the future but not now.” The appeal of this street that does not exist is captured in more specific terms in this passage, from a very different book:

But where for some the life option of going into the city meant choosing Wall Street, or Madison Avenue, or Broadway, or the Upper West Side, for me it meant committing to the emergent bohemia of my coming-of-age.

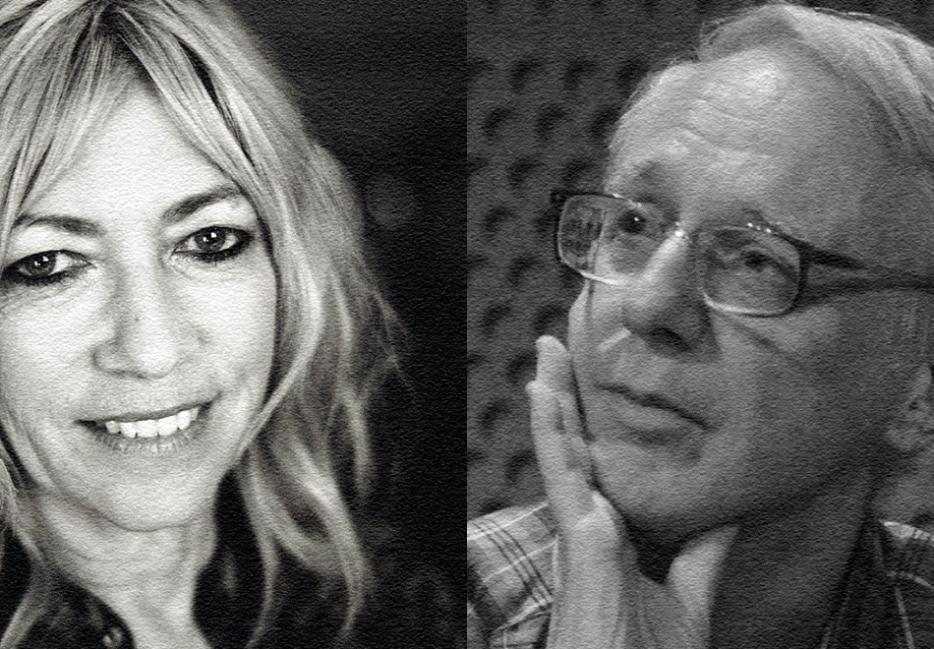

That’d be Robert Christgau writing about his own move to downtown New York in his memoir Going Into the City: Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man. It’s one of a host of works to emerge in recent years, written by crucial figures from the city’s 1970s music scene. Though Patti Smith’s 2010 Just Kids was far from the first memoir by an iconic downtown musician–Jayne County’s Man Enough to Be a Woman was released in 1996–it may have made the most seismic impact. It won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, and was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award for memoir. Richard Hell’s autobiography I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp came out in 2013. This year brings with it—along with Smith’s follow-up, M Train, in the fall—both Christgau’s memoir and Girl In a Band, by Kim Gordon (of Sonic Youth, Body/Head, Free Kitten, and more).

It’s easy to see why these books have appeal beyond fan enthusiasm for the authors’ earlier work. Smith has been a vital cultural presence for decades. Gordon’s work with Sonic Youth remained groundbreaking right up until that band’s final shows, which coincided with the end of Gordon’s marriage to fellow co-founder Thurston Moore; the album from her current musical project, Body/Head, has also earned abundant acclaim; and her creative output extends to fashion and the art world. Hell’s body of musical work is less vast than Gordon’s or Smith’s, but his role in New York punk history, both musically and aesthetically, was huge; since the 1980s, he’s become a critic and occasional curator. And Christgau occupies a rarified position among critics: his Consumer Guide reviews inspire a sort of monastic devotion and study by certain music fans, and his status as the self-appointed Dean of American Rock Critics. And while, broadly speaking, a reader’s expectations of a critic’s memoir and a musician’s memoir may differ, these books blur the lines of professional distinctions. Christgau’s includes a fair amount of literary criticism, for instance. And Gordon, Hell, and Smith all have sizeable bodies of work as writers in addition to the groundbreaking music they’ve made—Gordon’s on art, Smith’s poetry, Hell's poetry and fiction—which no doubt informed these latest efforts. Tell-all backstage memoirs these are not.

*

Not surprisingly, these writers turn up in one another’s books. In Girl In a Band, Gordon alludes to Christgau’s role as a critic in relation to Sonic Youth and the origin of the title of Sonic Youth’s EP Kill Yr Idols:

... a name we took from a Robert Christgau quote. Robert was the other big music critic of the time along with Greil [Marcus], but he basically ignored us. Robert and the Village Voice, the downtown New York City weekly he wrote for, were never sympathetic to Sonic Youth or to the local rock scene in general, and the one night he came to one of our shows, someone in the audience tried to light him on fire. Playfully, though.

Christgau, in the introduction to his book, writes that Hell’s is a “recommended memoir,” but also criticizes its author for “fail[ing] to indicate how their wives changed their lives and I bet their work.” A sense of interrelatedness inherent to the scene suffuses these books. Much of the first half of Going Into the City deals with Christgau’s partnership with Ellen Willis; in a 2011 review of Out of the Vinyl Deeps and Kevin Avery’s biography of Paul Nelson, he notes that “with Ellen Willis I have no ‘objectivity’ whatsoever—we were a couple from 1966 to 1969, and, except for my wife, no one has influenced me more.” Christgau’s wife, Carola Dibbell, plays a significant role in the memoir as well, with their shared observations on culture (and literature in particular) propelling the book forward. (Readers intrigued by Christgau’s writings on Dibbell’s fiction should take note that her novel The Only Ones is due out in March from the excellent independent publisher Two Dollar Radio.) In Just Kids, Smith famously chronicles her friendship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe, with some passages focusing entirely on his life, rather than events they experienced together.

Gordon’s memoir chronicles her move with Moore to Massachusetts, and writes warily about life in New York: “I’m equally mistrustful of the energy bursts New York gives you, which fragment and exhaust you. Living there gives you a phoney sense of self-importance and confidence.”

These memoirs place an emphasis on collaboration: Those seeking insight into the creative process within Sonic Youth, and how it evolved over the years, will find plenty to savour in Gordon’s book. In Christgau’s book, the collaborative role is more in the shaping of an aesthetic and the expansion of one’s tastes and areas of interest. Besides the influence of both Willis and Dibbell, he credits (among others) the writings of Barry Michael Cooper for pointing him in the direction of hip-hop in the late 1970s, and Original Music co-founder John Storm Roberts for introducing him to Afropop.

*

The subtitle of Christgau’s book—Portrait of a Critic As a Young Man—gets at the heart of part of these books’ appeal: they’re origin stories. Many of them begin with their authors far from New York City, and track their journey there. In Gordon’s case, it was California by way of Toronto, a sprawling journey that includes appearances from “Tonight’s The Night” inspiration Bruce Berry and iconic art dealer Larry Gagosian. Gagosian’s appearance in Girl In a Band is echoed by Andrew Wylie’s presence in Smith’s and Hell’s books, long before he was one of the most high-profile literary agents in the world. The origin stories here aren’t just those of the authors of the books in question.

Christgau’s journey is less a geographic one—he came of age in Queens—than an intellectual one, shifting away from the faith in which he was raised and developing his own distinct ideological and aesthetic consciousness. It’s a process documented throughout Going Into the City, encompassing his involvement with a number of left-wing groups. As much as this book covers Christgau’s musical and literary aesthetic, it also sets out the process by which his politics evolved, explaining what he took from his time with several disparate groups, never quite gelling with any of them, but embracing the potential of the time.

Nostalgia for that potential is hard to shake. The neighbourhoods where Smith, Hell, Christgau, and Gordon largely set their books are no longer home to the 21st-century equivalents of their younger selves. In a 2010 conversation with Jonathan Lethem, Smith said that “New York has closed itself off to the young and the struggling,” and suggested seeking out Detroit and Poughkeepsie. Gordon’s memoir chronicles her move with Moore to Massachusetts, and writes warily about life in New York: “I’m equally mistrustful of the energy bursts New York gives you, which fragment and exhaust you. Living there gives you a phoney sense of self-importance and confidence.” Hell and Christgau, by contrast, still reside in the city; across these four books, readers will find equally compelling arguments for a life spent in New York, and for knowing when it’s time to make a graceful exit.

Earlier in her memoir, Gordon writes about architect Aldo Rossi, who “believed that cities never shake their histories, that they preserve the ghosts of their pasts through time.” And reading these books can feel like an extension of that, from the summoning of figures no longer with us to the hearkening back to a previous era of life in New York, one which cultural changes and the real estate market have pushed out of reach. “Talking about New York is a way of talking about the world,” Whitehead writes towards the end of The Colossus of New York, and these books’ explorations of how their authors’ lives were shaped by the city feel both unique and, in their own way, archetypal. And in a time where questions of where artists and outsiders should go to seek their fortunes (critic Ben Davis’s take on this is both fascinating and bleak) are hotly debated, revisiting the city’s past can be useful—not for nostalgic reasons, but to see what the essential qualities of the experience were. Do these books offer a glimpse into a lost history of the city? Yes. But they also detail the shape of artistic consciousnesses, surrounded by narratives that double as journeys both geographic and intellectual. There’s the pull of nostalgia, for a definitive era in a definitive city. But there’s also the perennial appeal of these books for those who aspire to make art of any variety: they remind us of the potential that exists in stories and cities, and the narratives that can emerge from them both.