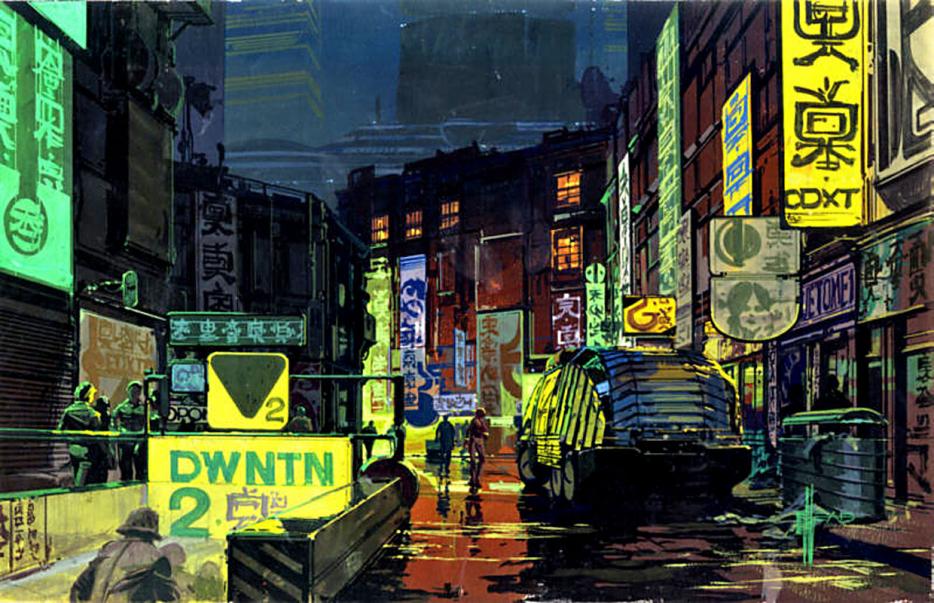

As the camera pans over the dystopian vision in Blade Runner's Los Angeles, it is obvious that something has gone wrong. Here is the world, it proclaims, plunged into perpetual night by corporate greed and too much metal and smoke.

This is one kind of horrific possibility. The real Los Angeles is simply another, a city built around the car (and only now starting to change). Both the fictive and the real Los Angeles are places borne of a poorly thought out embrace of technology, the dystopian reality of each a result of a too-eager adoption of the new.

Now, it seems, history may bring us the iCar. As fictional as the idea sounded just a few short weeks ago, with Apple having hired a collection of auto and battery engineers, what once seemed like absurd speculation is increasingly likely. Though no one is quite sure what an Apple-designed car might look like—or if it will ever be made—the general idea is just what one might expect: a focus on design, an emphasis on the high-end, probably electric, and possibly self-driving, too. The same company that turned selling pocket computers into the most profitable business on Earth may become 21st-century successors to Henry Ford.

Apple has, for the past decade, been seen as a kind of barometer of where things are headed, and also held up as a paragon of “how-things-should-be-done." It's no surprise that, in response to the car rumours, the tech world is focused on the market opportunities of any and all moves by Apple. Predictably, the iCar analysis and think pieces from the usual suspects have been breathless. Emphasis has been on the viability of such a move, and whether or not it fits within the company's culture, ethos, and financial goals.

Funnily, though, few seem to have asked a simple question: do we actually want a company with a brilliant knack for stoking desire to make a car? The idea of Cupertino's advertising machine putting its weight behind what, only recently, felt like a fading twentieth-century idea feels, if not exactly at odds with the time, an unexpected and even ominous left turn. As the richer parts of the world continue a migration back into cities and toward the mantra of "walkable and sustainable living"—even Los Angelinos are now funding public transit—here comes the emblematic company of the times to build, of all things, an automobile.

Given Apple's track record of success—and analysts' record of getting its potential for success wrong—it is worrying to think of what a runaway iCar could do. The difficult political battles being fought over the role of the car and road in our increasingly urbanized world might find an unexpected dynamic in a newly car-friendly consumer. Urban sprawl, the dominance of the car, and the networks of energy that power them, be they gasoline or electric, are issues with enormous consequence, and it's difficult to think of a field in which corporate and environmental concerns have less in common. Yet, so much about the pretty renders of near-future urban existence are about selling a lifestyle; and what better to appeal to middle-class visions of the ideal life than a shiny, white, electric iCar?

On first glance, an electric car made by a company famed for design sounds like a step in the right direction. All the same, the place and function of technology is hard to predict. As increasingly influential mobile analyst Benedict Evans wrote in thinking about the Apple Car, once the internal combustion engine was invented, it was easy to predict the obsolescence of the horse-drawn carriage—far more difficult to foresee was Walmart. So rather than thinking about any kind of iCar as a simply a better-designed Honda—one without, say, the maddening interfaces that sit in the dashes of most modern autos—there are other factors to consider: not only a new appreciation for the car, but the idea of self-driving car, or the car as a service—not a thing one owns, but that one buys into, fleets of pristine, ghostly vehicles prowling the streets of their own volition, waiting. What we know as the car is about to undergo a profound shift because, already, driverless cars are legal in more than a few jurisdictions around the world.

The same company that turned selling pocket computers into the most profitable business on Earth may become 21st-century successors to Henry Ford.

In thinking about the potential for the iCar, however, Evans goes on to suggest that the self-driving iCar might represent a kind of "unbundling"—the term analysts use for the propensity of digital technology to "disintermediate" established networks and break them into parts, just as iTunes, Netflix, Google, and Facebook have all done in various ways. This type of discussion is unsettling. The thing being unbundled here is public transport: instead of a fleet of buses, an army of Apple Automobiles. The iCar as an idea—even if not a single one is ever made—represents an entirely new problem for the politics of the 21st century.

What underpins something like Evans' reasoning is a model of thinking that views the unfolding of technological and capitalist history as an ever-increasing march toward privatization and individualism. Such "disruption" is already beginning to occur. AirBnB has been a boon to thrifty travellers, but at scale, also allows a shrinking property-owning class to produce income from their assets by renting to those less wealthy. And if AirBnB might be thought of as mostly ambivalent, ride-sharing service Uber is arguably more insidious. Already valued at a startling $40 billion, as was outlined in a great piece by Johna Bhuiyan in BuzzFeed, Uber is not only disrupting the taxi industry in cities around the world, but, through a shockingly entitled approach to regulation, may begin to affect public transit in some underserved cities in America. Maybe most importantly, it is reshaping the relationship between government, labour, and law because its users have become its greatest advocates. Politicians, as always, simply bend the way the voters ask them to. With Apple so universally beloved by its users, one only imagines the kind of pressure that might be exerted to let them have their way when it comes to the car.

These are the effects of digital technology that few had the foresight to imagine. I know that I, excitedly salivating over each new iPhone release, never dreamt of such change. But the liberation that comes from being able to do so much with our pocket computers has in turn produced multi-billion dollar entities that, in positive, benevolent, and insidious ways, can use that capital to effect enormous change. Unfortunately, the unintended consequences of that change are often so murky and deeply interwoven with a plethora of factors, it is almost as if one has to let mistakes happen at scale just to recognize that they have occurred. Who, after all, could have imagined that an app on your phone for getting a taxi ride might, as Farhad Manjoo argued in the New York Times recently, one day herald a reorganization of labour practices? But this is a perfect description of Uber: as job stability decreases and income inequality grows, the freelance service economy grows with it. We are, much to our own surprise, all UberX drivers now.

Today, Apple introduced its Watch. Like the iPhone before it, it is hard to accurately predict what ends it might be put to or what effect it might have prior to seeing it in use. Few envisioned that along with connecting, helping, and informing people, a smartphone would engender a culture of surveillance, fear-of-missing-out, or distraction. It seems likely, though, that given the Apple Watch's announced health tracking features, potentially intrusive notifications, or simply the unknown apps yet to be made, it too may also usher in a whole new range of not just ambivalent habits and behaviours, but emotional and ethical quandaries, too. If the smartwatch becomes truly popular, who knows what the world might look like after eagerly adopting newest invention?

Yet with the hype-machine steadily building for months, first stoked by Apple, then set aflame by a credulous press with a tech fetish, it is in a sense already too late to ask these questions. The way the market works means that individual desires, collected, elicit social shifts, the effects of which are almost impossible to predict. An equitable to response to history is thus always a kind of unraveling—figuring out after the fact that we need to hit the brakes or the undo button. The only thing you can do in the meantime is to look at the ideology of those pushing new ideas—to see if, in their words, there are shades of those things we have had to undo already. A word of warning, then: if the Apple Watch is being pitched to us as the next iPhone, and the Apple Car is being sold an unbundling—products that will continue the work that Silicon Valley has already begun—then at the very least, we should be deeply skeptical of what shimmers beneath the utopian pitch of a cleaner, brighter, Apple-powered future.