As the year-in-review engine chugs along, keeping track of narratives in the year’s art and culture offers its own rewards: a window to see how different writers have made sense of the year. One theme that seems to be emerging as critics discuss the year in books is the rise of the essay: at the Barnes & Noble Review, Michelle Dean focused on a number of essay collections written by women; at Flavorwire, Elisabeth Donnelly’s look back at highlights of the year in nonfictionincluded works by Rebecca Solnit and Leslie Jamison, praise of whom has been common in these pieces; and Jason Diamond took an extensive look at the year’s landscape of essays at Electric Literature. (Full disclosure: Elisabeth and Jason are friends of mine; Jason and I are also colleagues at Vol.1 Brooklyn.) Among the works making appearances on many a year-end list is Charles D’Ambrosio’s Loitering: New & Collected Essays. That “collected” part speaks to the volume’s history, which could also serve as a sort of mile-marker in terms of the changing role of how essays have been received in the past decade and a half. Many of the essays found inside were first released in Orphans, published almost a decade ago by Clear Cut Press, a small outfit that released about a dozen books total before ceasing activity. Loitering, by comparison, has been given a (literary) hero’s welcome, including a conversation between D’Ambrosio and Jamison that appeared on The New Yorker’s website.

“I wrote the earliest of these essays for [Seattle alt-weekly] The Stranger in Seattle because no one else would give me five thousand words and then agree not to change a single comma–exactly the kind of hard bargain you can strike when you’re willing to work for next to nothing.” That’s how D’Ambrosio sets the stage for Loitering in an introduction that, like much of his work, blends literary analysis with his own wrenching familial history. It’s the kind of thing that, in untrained hands, can seem forced, but for D’Ambrosio, this combination works; it’s a juxtaposition that is, in its own way, implicit in the form. In his introduction to 2014’s Best American Essays, John Jeremiah Sullivan delved into the origins of the essay, and of its continuing popularity over the centuries. After recounting a number of points of historical convergence, he reaches a conclusion about the form’s continued malleability:

The modern essay—the form we continue to play with—develops not in any one country but within a transnational vibrational field that spans the English channel. It assumes many two-sided forms: trial / try, high / low, literature / journalism, formal / familiar, French / English, Eyquem / Ockham. The vital thing is that the vibration itself be there.

The line between the essay and other forms of nonfiction is not always clearly defined. Last month in the Washington Post, Eve Fairbanks argued that the popularity of essays was having an adverse effect on journalism. For some, the concept of the memoir is indistinguishable from the personal essay; for others, the line between food or travel writing and an essay is a wavering one. Does that blurring suggest readers and editors are simply conflating the forms, or is it a sign that the essay has become ubiquitous, to the point of assimilating other styles of writing in the popular imagination?

This year, we’ve had a pair of acclaimed essay collections—the aforementioned Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams and Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist—become New York Times bestsellers. This isn’t necessarily a shock: both Jamison and Gay are terrific writers whose work taps into widely held concerns—how we relate to one another, the state of race in contemporary American society, the limits of human endurance physical and emotional. Jamison’s collection was the winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize, while Gay’s book was released on Harper Perennial, an imprint that has also released experimental fiction by the likes of Blake Butler and Ben Greenman. It’s worth mentioning that Gay and Jamison both write fiction as well: Jamison’s novel The Gin Closet was released to much acclaim in 2010, while Gay’s first novel An Untamed State also came out earlier this year, following a short collection entitled Ayiti in 2011.

And, under the auspices of essays, more experimental work is making a significant foothold. Matthew Gavin Frank’s meditation on the giant squid, Preparing the Ghost, is billed as a book-length essay, and blends observations of the squid and its first photographer with ruminations on Canadian geography, Borscht Belt resorts, and the author’s own somewhat obsessive quest to gain entry to the home of Moses Harvey, the first person to photograph a giant squid in 1874. (This passion for nontraditional nonfiction extends to longer works as well. John D’Agata’s study of Las Vegas, About a Mountain, is being adapted for film. And Kerry Howley’s Thrown, which observes the mixed martial arts community, has received glowing attention from both the literary community and those who write about, and participate in, the world of professional fighting.) The continuing rise of essays has even begun to affect work in other genres. Consider the title character of Brian Morton’s acclaimed novel Florence Gordon, a political essayist who unexpectedly receives a late-career critical and commercial boost, to say nothing of HBO’s Girls, which features an essayist as its main character, and whose creator released an acclaimed essay collection herself earlier this year.

There are, I believe, two converging impulses that have led to this moment—one from outside the literary world, the other from within it.

The same impulses that prompted someone in 1994 to type up or write their thoughts, make a series of copies, and staple them together might have led them, a few years later, to create a profile on a site such as Diaryland or LiveJournal and publish their thoughts there instead.

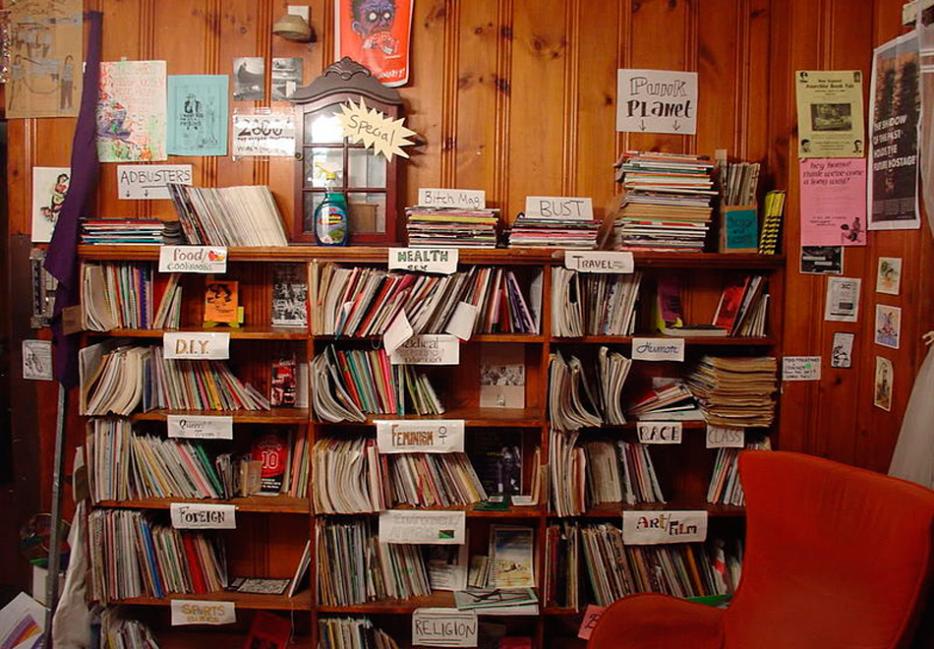

For the former, it’s worth making a jump to the hardcore punk scene of the mid-’90s. Go to a show and, at tables opposite the stages on which bands played, you’d find for sale an abundance of half-sized zines, mostly composed of personal writing. These existed in contrast to the larger zines that focused more on music, with scene reports, interviews with bands, and reviews of records. (I edited one myself.) Taken together, they seemed of a piece, part of a larger ecosystem: you could find ads and reviews for personal zines in those that were more music-oriented, for instance. And while zines of all sizes still exist, they’re nowhere near as ubiquitous as they once were. Some of that—a lot of that—is thanks to the Internet. The same impulses that prompted someone in 1994 to type up or write their thoughts, make a series of copies, and staple them together might have led them, a few years later, to create a profile on a site such as Diaryland or LiveJournal and publish their thoughts there instead. The correlation may not be one-for-one, but you can at least see the shadow of a line traced between the two.

From there, an audience grew, and a generation came of age reading longish-form nonfiction writing, often personal in nature, as part of a movement that emphasized egalitarianism. Somewhere along the line, that became monetized: outlets such as Thought Catalog have found success publishing essays and other pieces of personal writing online. Sometimes, as with Gavin McInnes’ transphobic diatribes, the range of their output has worked against them, but talented writers have also found a home there, whether for shorter pieces or longer work. Anecdotally at least, the audience for personal nonfiction seems to be continuing to grow, both in terms of readers and writers. Consider the rise of Medium, for instance, which has attracted writers such as Paul Ford and Darin Strauss and features writings on topics cultural and technological, or even the online newsletter company TinyLetter, where you can find everything from scenes from one writer’s life to daily roundups of fascinating facts and stories. Earlier this year, The Stranger’s Books Editor Paul Constant called newsletters “a more intimate way to learn about the news, one perspective at a time.” And the involvement of technology has also made the stuff of one decade’s Xeroxed confessional writing about families or relationships or art the material from which technology startups are born.

The last 10 or 15 years have also seen a renewed focus on the essay from within the literary community. The recently released Happiness: Ten Years of n+1 collects, as the subtitle suggests, highlights from the literary magazine’s first decade of existence. And while the publication is known for its somewhat stylized house voice and thorough literary (and cultural) criticism, you’ll also find fantastic essays in here: Elif Batuman’s “Babel in California,” both a meditation on Isaac Babel’s work and an account of a conference dedicated to it, and Wesley Yang’s “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho,” about isolation and the man who murdered 32 people at Virginia Tech, among them. In her introduction, Mary Karr recounts meeting founders Keith Gessen, Mark Greif, and Benjamin Kunkel, and observes that the magazine “ponied up with the promised luminary unknowns–those Susan Sontags- and George Orwells-to-be emerging like sirens from the fog of oblivion into print.”

The year before n+1 debuted, the first issue of The Believer hit shelves. Read Harder, an anthology released in September, collects nonfiction published in that magazine over the last five years, including work from the likes of Lev Grossman, Francisco Goldman, and, once again, Leslie Jamison. (Jamison’s essay “The Immortal Horizon,” about a particularly grueling ultramarathon, can also be read in The Empathy Exams.) Like n+1, the magazine quickly became a destination for longform writing, written with intellectual rigor and a sometimes esoteric focus. And, also like n+1, The Believer came from within an existing literary community. Charles D’Ambrosio wrote about finding a home for his early work in The Stranger in the mid-1990s; a version of D’Ambrosio looking to place his work in 2008 or 2009 would have far more options.

The essay, as a form, can inspire introspection and make the familiar seem revitalized, or entirely strange. D’Ambrosio’s Loitering closes with an essay titled “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg,” which takes its title from the Richard Hugo poem of the same name. It begins with a lyrical examination of the same Montana town that inspired Hugo before shifting into an analysis of Hugo’s poem that’s both affectionate and irreverent: “The poem’s not fragile. You can beat on it. It’s got good traction.” From there, D’Ambrosio shifts from Hugo’s evocation of despair and desperation to his own. He never loses sight of Hugo; he never quite lets the reader forget the poem that inspired the essay that’s now being read. And in doing so, he can cover his own personal history and eventually join up with Hugo’s legacy: in the final pages of D’Ambrosio’s essay, he himself inhabits some of those same spaces. In there, he ties the history of a place together with the history of Hugo’s poem; he reminds the reader of the writer’s ability to unwrap history and reveal quiet tragedies to the world. In this piece, and the book as a whole, he makes the case for why the essay works so well for both.