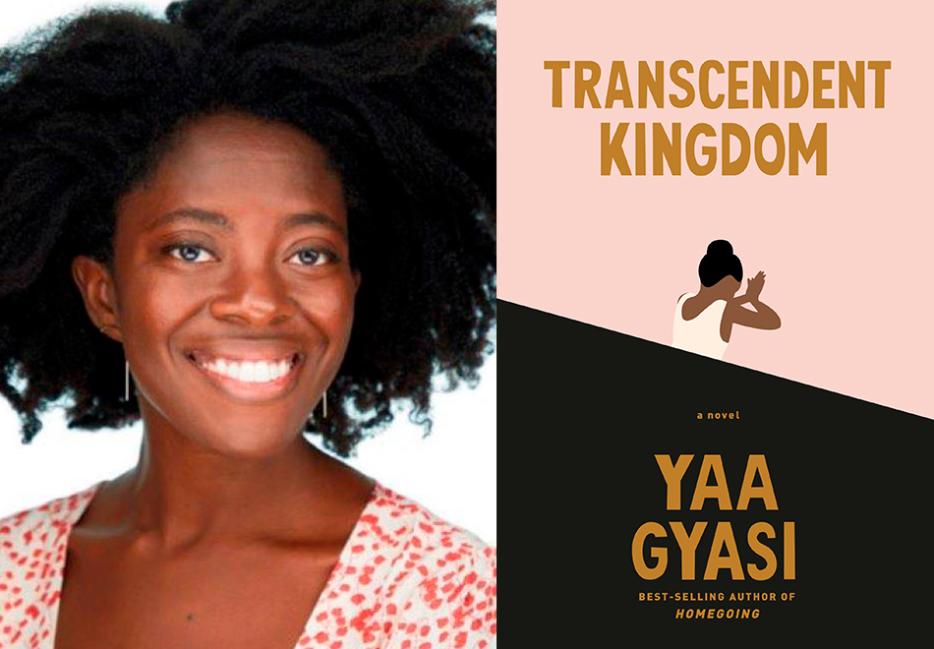

Around the same time Yaa Gyasi finished the first draft of Homegoing, her sweeping debut novel examining the impacts of slavery on one Ghanaian family across seven generations, she also wrote a short story about a scholarly young woman whose religious mother comes to live with her. Gyasi put that story aside, finished Homegoing and became a bestselling author at 26 years old. She mostly forgot about the short story, but its narrator’s voice stayed with her.

That voice would eventually find a home in Gifty, the narrator of Gyasi’s sophomore novel Transcendent Kingdom (Bond Street Books). Gifty is a young neuroscientist at Stanford who is studying reward-seeking behaviour in mice. It’s a PhD thesis she insists is unrelated to her brother Nana’s fatal opioid addiction, or her mother’s debilitating depression.

The novel deftly weaves between Gifty’s present life as an anti-social grad student and her religious childhood in Huntsville, Alabama, where Gyasi also grew up. Transcendent Kingdom focuses on one family, deeply exploring grief and trauma, race and class, science and religion.

Transcendent Kingdom is at times poignant, funny, and painfully prescient in its exploration of the opioid epidemic. Last month, Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges for its role in the opioid crisis, admitting that it paid doctors to write more opioid prescriptions. Transcendent Kingdom offers a realistic and heartbreaking portrayal of the human costs of the casual over-prescription of opioids.

I call Gyasi while she’s at home in Brooklyn, where we chat about keeping journals during the pandemic, internalized racism, and rooting for deplorable characters.

Samantha Edwards: I imagine this is a really hard time to put a book out into the world, but it’s also such a good time to read. Over the last couple months, reading a physical book feels like the only thing that forces me to not to scroll endlessly through my phone. What’s your focus been like during quarantine?

Yaa Gyasi: It ebbs and flows. I’ve probably been able to read more in these past few months than I did before we went into lockdown. But there are moments when I do find myself glued to my phone or laptop refreshing different newsfeeds. But I think one of the good antidotes to those anxious feelings is to read.

What are some books that you’ve read lately that have been a good antidote?

I really enjoyed Luster by Raven Leilani, which is a work of fiction. I loved Memorial Drive by Natasha Trethewey, a beautifully written memoir that made me cry. I read Zadie Smith’s Intimations, which is a collection of essays. It’s the first thing I’ve read that deals with this present moment and in a lot of ways I found it really interesting and helpful to be able to contextualize what we’re seeing now. I read Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler, which I think is the only kind of apocalyptic book I’ve read in the last few months. In addition to being prescient, I just found it to be clear-eyed in its understanding of the problems facing America, certainly capitalism and racism.

I still need to read Intimations. I’m so impressed that she was able to write and publish a book during the pandemic. I listened to an interview with her on the podcast “Call Your Girlfriend” and she said how she has to write; she has no choice in the matter. It’s pathological.

I think there are so many ways people approach their writing. I’m not that kind of a writer. I don’t feel like I need to write every day. When I’m obsessed or once I’m firmly inside a project, I will write every day, but I don’t generally feel an anxiety about not writing in the fallow period.

In Transcendent Kingdom, Gifty journals a lot as a kid and as an adult, and lately I’ve been thinking about how I wish I was keeping a journal right now so I could remember what this period was like. Do you keep journals or diaries? How do you track your present life?

I actually don’t. Even when I was a child, I wasn’t that interested in journaling. I lazily kept a journal where in a three- or four-year period I probably wrote 100 entries. It wasn’t a daily practice and it never felt serious or sustainable for me, probably because I was already writing fiction at that time. Also, I could feel even as I was trying to capture the events of my day, there was something performative creeping into the writing in a way that I felt was not the purpose of a journal. I just knew I would rather be making things up.

There’s a scene in the book that takes place while Gifty’s doing her PhD, where it’s revealed that she grew up in an evangelical church. Her classmate Anne asks if she believes in evolution, and then is sort of stunned when Gifty says of course. Throughout the book there’s this idea that religion and science are at odds with each other, that you can’t believe in both. Can you speak about that relationship for Gifty, someone who finds comfort in God, but also science?

Gifty’s comfort with religion has to do with her the fact she grew up in Alabama. I also grew up in Alabama and something that I’ve noticed as I’ve left and lived in other places is that in Alabama, there was not a very clear separation between church and state. People’s religious lives were very much worn on their sleeves.

Gifty’s raised Pentecostal by an incredibly devout mother and she herself is quite devout as a child. Part of the thing Gifty loved about religion is the certainty, the assuredness, the fact that there are rules to follow and if you are following them, that presumably means you are getting closer to some ideal. But her family is also the only Black family in a predominantly white church in Alabama, so she is constantly confronted with these opinions and viewpoints that in some way negate her experience, or are critical of her for reasons she has no control over. The racism she experiences in her church start to complicate her understanding of God, so we start to see her turn away from the church, particularly in those years where her brother’s addiction begins to surface.

Opioid addiction plays a large role in the book. I had read that the character of Gifty was partially inspired by a real friend of yours who is a neuroscientist and studies addiction and depression. What else inspired you to write about opioids?

In the years I started working on this novel, there was so much writing about the opioid epidemic here in the States. I found the articles and the documentaries really sensitive, nuanced, and humanizing. Also, for the first time that I could remember, the articles were willing to interrogate the role of pharmaceutical companies in creating this problem and to look at the drug trade as a response to the economic crises in a way that I hadn’t seen before. I really appreciated all of this work.

But I also thought the fact that they were talking about drug use as an issue demanding a healthcare response was specifically because this crisis is affecting white people in rural and suburban areas primarily, rather than the previous epidemics of crack and the existing epidemic of heroin among the Black community that was in cities and incredibly heavily criminalized. At any rate, I just felt like this was an opportunity to write about this crisis in another similar humanizing, nuanced, attentive way, but to not leave Black people out of the story.

There’s that scene in the book where Gifty is at a dinner party with a boyfriend and he and his friends are discussing big issues like the opioid epidemic, prison reform, climate change. This moment makes her think about how people feel like they need to weigh in and have an opinion. She wonders, what’s the point of identifying problems and circling them, if it’s not followed by finding solutions? It made me think about how right now, a lot of people and companies are “learning and listening” when it comes to racial injustice and police brutality. We’re spending a lot of time talking about problems as if identifying examples of systemic racism is enough.

Gifty has experienced some of these traumas personally in ways that the people who are talking about them have not, so it feels kind of disingenuous to her to see people talking about things that they don’t know about on a visceral, tangible level, especially when she herself is not a very talkative person but has experienced these things.

But in terms how I’m seeing this present moment of “listening and learning,” it’s hard to know. So much of it does seem performative and superficial. I think books are really important, but I also know that it is possible to read a book and then do absolutely nothing to change your real life. Books are not substitutes for real life, certainly novels are not substitutes for real life, and the characters in novels are not substitutes for real people. If you are taking the time to read books by Black authors and you are even going to protests or donating to organizations, but you are not interrogating the ways you yourself are implicated in these problems... have you moved to an all white suburb? Do you send your children to predominantly white schools? Do you oppose legislation that would allow affordable housing to be built in your neighbourhood? I think all of these things that implicate you are more important than buying a book by an author that is talking about racism.

It’s easier to donate $50 to a bail fund than having to personally interrogate your own beliefs and actions. It’s a lot harder to acknowledge these deep-rooted prejudices that exist within yourself.

Discomfort is uncomfortable. It’s not something that people want to use and relinquish their comfort, which is what I think would actually need to happen for substantive change to be made, for white people to give something up. We often talk about racism as a system that is unfair in that’s disadvantaging Black people, but the other side of that coin is it unfairly advantages white people. That piece, the fact that white people are gaining these advantages based on nothing they’ve done to deserve it, I think that white people still need to come to terms with.

Early in the book, when Gifty is invited to join a “Woman in STEM” group, she laughs it off. She doesn’t want to be considered “a woman in science” or a “Black woman in science.” Why does she push back against that categorization?

I think that moment’s really telling because we’re seeing Gifty displaying internalized racism, certainly internalized misogyny. She has internalized these messages of what it means to be a woman and what it means to be Black. She feels that her self-worth, her professional worth, is in peril if she admits those two things or allows them to define her work. Yet I think it only enriches her work and it’s one of the reasons she thinks about questions that maybe her colleagues are not thinking about. It’s only expansive, not detractive, but she can’t see it.

This is something I didn’t really think about while I was reading, but yes, as a reader, there are things that we catch on to before Gifty does.

I spent a lot of time thinking about how to work with the first person because I’ve never written anything in the first person before for longer than a short story. I was thinking about books that were written in the first person that I really like or admire. I think of Gifty as an unreliable narrator in many respects. I think she’s a character that is often saying something that is not necessarily in line with her actions. I’m thinking particularly of when she protests the idea that her work has anything to do with her personal life. She says things like, “I chose this because it’s the hardest thing that you can do,” and not because it directly impacts her mother and brother. She’s a character that, we know more than she does, mostly because she is not really willing to examine herself. Because she won’t look at it directly, I, as the writer, had to find other ways to allow us to see it. But what it means is that Gifty is not always likable and she’s not always reliable.

She is unlikable, and yet if something is in the first person, it’s my instinct to root for the protagonist. I’m too sympathetic!

I think that’s what point of view does. It’s what we’re trying to do, to give the point-of-view character the benefit of the doubt. I’m thinking of a book like Lolita, it’s in the first person and Humbert Humbert is obviously doing deplorable things and he’s indefensible at every turn, but because it’s in the first person, you are kind of watching this train wreck unfold, and not that you’re siding with him, but you’re having to work against his unreliability as a narrator. I think that’s one tool the first person gives to the writer. But it’s not the only way. Marilynne Robinson wrote Gilead in the first person and you believe and trust everything that John Ames says because he is believable and trustworthy and he’s willing to question his own motives. Gifty is somewhere in the middle of those two. There are moments where she’s not being fair, trustworthy or reliable, but there are moments where she does take a second look.

Why did you decide to write in the first person?

It just felt natural. The story was so clearly Gifty’s story in every way, it wasn’t a scenario where I started in third person and then realized that first was right.

Homegoing and Transcendent Kingdom are so different in scope. What did you get out of those two writing experiences?

Homegoing covered so much, there was such a sprawl to that book, it really allowed me to think about the ways in which the present is in conversation with the past, and I think the structure really accommodated that. For Transcendent Kingdom, I think that it was a similar question about how we deal with traumatic history, but on such an intimate scale and with such a single lens that I think made it so much more personal.

What’s something that you’ve learned about yourself between writing Homegoing and now?

Well, I had always wanted to be a writer since I was young child. I think after Homegoing there was a stretch where I wasn’t writing as much as I typically do and I felt the first time in my life this doubt of whether or not this was something that could sustain me and sustain my attention. After writing Transcendent Kingdom, I feel more trusting of my ability to find my way through a story.