I got into basketball the way some people get into drugs or religion: during a bad time, as a means of cheap transcendence. This was a few years ago, in the middle of a dark and difficult winter, when I was feeling particularly vulnerable—deep in the kind of permeable, thin-skinned state that best primes a person to join a cult.

Instead, I went to a Toronto Raptors game. My boyfriend, a lifelong NBA fan, had acquired two tickets and gently suggested that maybe I could use a trip outside the house. Walking up the steep stairs to our cheap seats, I remember feeling terrified of the height, certain I was going to fall backwards and roll off the edge of the balcony to my death. When we sat down I white-knuckled the back of the seat in front of me, my vision darting nervously around the arena, until suddenly I clocked the hardwood and something clicked into place. Once I was looking at the court, the scale of everything around me seemed to telescope and shift. My view of the game anchored my attention so completely that everything else in the stadium fell away.

Most big arenas, of course, are designed like this on purpose, so that you can see what’s happening with relative clarity no matter how high up you are. But in that moment, I felt less like I was experiencing a standard architectural feature and more like I was at the centre of an astounding manipulation of dimension and scale. For a minute, I forgot how high up I was, forgot to be nervous about it—forgot, for the first time in forever, to be scared of anything at all. This simple collapse of distance had done what weeks of deep breathing and doubled-up therapy sessions couldn’t: it had sorted my sprawling attention into a single, focused order. Magic, I thought. But real.

Once I was primed for revelation I caught it everywhere: in the balletic slope and speed of play, the psychic qualities of good passing, the emotional weather of the crowd. I was enthralled, too, by the structure of the game—not just when the players were playing, but the little interstitial skits and videos that came on at every time out. The whole night was an overstimulating, overwhelming spectacle, and I loved every part of it: the teens pitching T-shirts past my head, the big inflatable mascot trying to eat the security guard, the noise meter, "Kickstart My Heart," the Kiss Cam. The Raptor running across the court, the Raptor waving a flag, the Raptor banging a drum. By halftime, I was fully converted.

When the buzzer sounded for the end of the second quarter, everyone around me jumped up out of their seats, headed for popcorn and beer and the bathroom. As I stood up to let the people in my row move past me, I looked around and felt struck by the same vertiginous terror that had hit when I first came up the stairs. Gripping the cold plastic back of my bright blue seat, I tried to keep my attention anchored on the court. For a few seconds it was empty, and then, gradually, I noticed a group of twelve-year-old girls gathering on the periphery. The announcer asked us to please welcome them, a local youth rec league who would be playing a game on the court for our halftime entertainment. There was a tiny smattering of applause. The girls ran out onto the court, ponytails swinging like pendulums.

At this point my boyfriend and I were the only people still sitting in our section. Together, we watched the girls pass and post each other up, shooting layups and three-pointers from the same positions where, just minutes ago, a crew of world-famous seven-foot-tall millionaires had been doing the same thing. It was as if, during the intermission of a Broadway show, a community theatre troupe got to come up onto the stage and do their own short play. I felt a whole new dimension added to the wonder I’d felt all the way through the game’s first half; something to do with scale and size, significance. I didn’t understand how people could be missing this part of the game. It seemed as important as any other—essential to the structure of the spectacle it was nested inside. I stayed glued to my seat until the game inside the game was over.

***

Halftime is a literal sideshow, a cute little feature at the centre of the real event. Most people don’t think about it much, so it’s difficult to find a lot of concrete information about its history. The shows started getting really good circa the late ’70s-early ’80s, when the beleaguered NBA was suffering from such low viewership that even the finals aired on a tape delay. Some franchise owners decided to inject a little circus-style showmanship into their games, making halftime a little more bombastic than the plodding gameplay that surrounded it. If you didn’t care about a bunch of guys trying to get a ball through a hoop, the logic went, perhaps you might still enjoy watching a local radio DJ wrestle a bear.

The contemporary halftime show retains this scrappy, slightly vintage energy, even as the game has changed radically around it. A typical performance (usually about seven minutes of the break’s total fifteen) has the anarchic, analog feel of public access television or a community talent show; there’s something about the format that seems to almost physically repel anything too fancy. If you Google “worst NBA halftime show” you’ll see a wide range of tragicomic turns by artists who have some degree of fame outside the stadium: Ja Rule’s viral flameout at a Bucks game last year, or 21 Savage, who played a Hawks game where his voice was so woefully out of sync with the backing track that his performance looked and sounded like a Shreds video. You can’t help but feel a little bad for these guys, who seem used to playing in places with sound systems that work, for crowds who bought tickets to see them.

Conversely, the halftime performers who look most professional and in charge of their shit are the ones who seem most accustomed to performing on a tarp—working against an echoing sound system, directing their energy at a sea of empty seats. Most of these acts fall into one of a few general categories:

- Kids and teens. School band recitals, dance performances, youth rec league basketball games. These are incredibly common, ostensibly because there is never any shortage of young people willing to play a basketball game for free. (Also, though they don’t always perform at halftime, I feel compelled to mention that the Raptors have an in-house youth dance crew called the LIL BALLAS who often perform to a medley of Drake’s greatest hits with one young child at the front dressed up in full Aubrey Graham drag, like with a penciled-on beard and everything. Few things are so simultaneously charming and stressful to watch.)

- Musical performances. At the All-Star Game you might get an actually famous musician, but for the most part these tend to be the kinds of performances you’d see at a county fair or Buskerfest: Hawaiian Soundcloud rappers, 13-year-old novelty violinists who play so fast you can’t even tell if they’re good or not, that kind of thing.

- Audience participation. Pretty standard stuff—your baby races, your creepy “professional Simon Says caller”s, your free throw contests, etc.

- Dance crews. God’s most perfect form of entertainment.

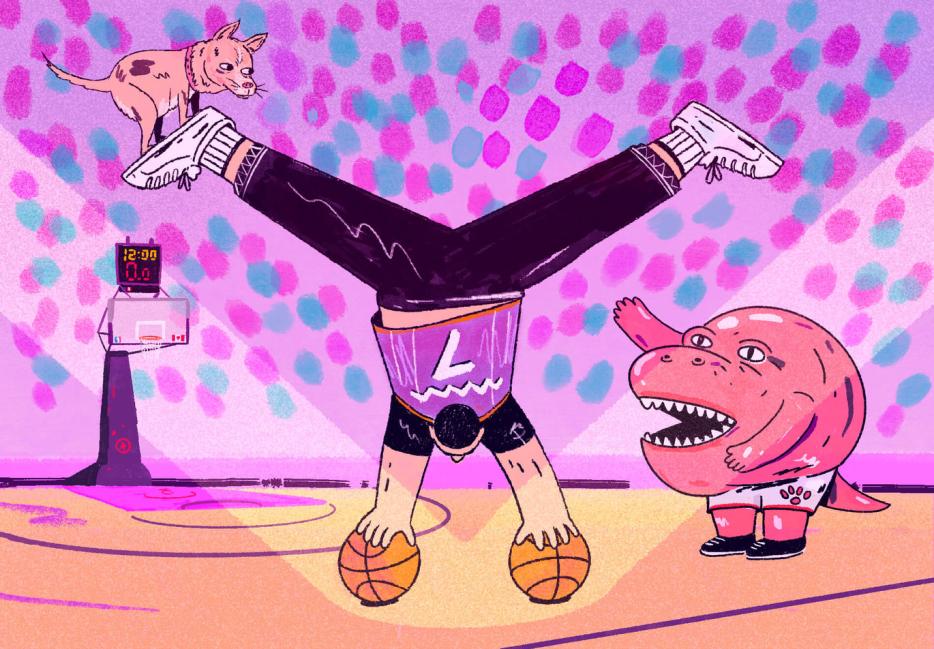

- Talent show-style acrobats. People with names like Rubberboy or the Human Slinky, people with entertaining pets, people doing handstands and precarious balancing on all kinds of equipment. There’s a lot of crossover between the performers in this category and high-ranking contestants from the TV show America’s Got Talent; the acts tend to have either the hair-sprayed perkiness of a figure skating performance or the campy, over-the-top masculinity of peak professional wrestling.

Almost every dedicated NBA fan has a favourite halftime performer, and almost all of them are drawn from this pool. I’ve told a few of my basketball-loving friends I’m working on this piece, and almost all of them have asked me whether I’m going to talk about their favourite act: the quick-change couple, or the woman who does a handstand on two canes, grips a pole with her mouth and shoots a bow and arrow with her feet, or the “human flag,” or the chair-stacking guy, or the dude with the chihuahua that crawls all over him while he does handstands on a pair of basketballs, or the mime who climbs the really crazy ladder. One friend asked me whether I was going to talk about “the speed painter,” and when I asked whether she meant the man I’d recently watched whip together a Nelson Mandela portrait in a performance that looked like Criss Angel doing Stomp by way of Bob Ross, she said No, I mean the guy who does that while singing. (Turns out there are at least three speed painters currently working the halftime circuit.)

The most popular and well-known NBA halftime performer is a woman named Rong Niu, who goes by the stage name Red Panda. She was born into a family of performers, spent her childhood in China attending a “boarding school for acrobats,” and has been doing the same act for nearly 30 years now. It is entirely useless for me to describe her performance when you are a single click away from watching it yourself, but just in case you can’t currently watch video, I’ll try.

Red Panda begins her act by riding a seven-foot-tall unicycle out into the middle of the court, where she balances for a few seconds next to an assistant (often, delightfully, a mascot), who begins to toss her some bowls. Once she has a couple in hand, she sticks out a leg, points her toes, and begins stacking the bowls up her leg—one upside-down, the next right-side up on top of it and so on, so they form a kind of tower. Then, with a single kick, she flips them up into the air where they land in a perfect stack on top of her head. Keeping the stack perfectly balanced, she gets some more bowls from the mascot, and stacks more and more of them up her leg, kick-flipping them into the pre-existing stack. By the end of her performance, she is often balancing ten bowls on her head while stacking another five up her leg. When she flips them, it’s genuinely astounding—a feat that seems so impossible you forget to wonder why she’s doing it in the first place.

Red Panda’s act is one of the few halftime shows that consistently kills—there’s real tension in it, heavy drama. Audiences actually stay in their seats for it, much to the chagrin of arena staff. (This, I have learned, is the best metric for measuring the quality of a halftime show—one former talent booker says that you know you have a good act on your hands if the vendors complain their sales are down.) I recently showed a video of her act to my grandmother, who is 92 years old and nearly impossible to impress, and within 30 seconds she was riveted. Red Panda is so beloved throughout the NBA that when someone stole her $25,000 custom unicycle from the baggage claim at an airport in San Francisco, the Golden State Warriors bought her a new one.

I think the thing that sets her apart from other halftime performers, besides the sheer impressiveness of her act, is the fact that her real feelings seem to float so close to the surface as she’s doing it. A lot of other performers are fun to watch, but they work with the same stiff cheerfulness as ballroom dancers—those fake smiles that never drop, like they’re straining to make sure you don’t see any of the actual effort they’re putting in. Red Panda appears confident as she balances and flips, but her expressions seem fluid, responsive and real. While she’s stacking the bowls you can see the effort on her face—and when she finally pulls off the flip, she always looks as genuinely thrilled and surprised as you feel.

It makes sense to me that NBA fans, in particular, love to see this; it feels of a piece with the up-closeness many people cherish about the sport. In its best moments, professional basketball can evince a weirdly intimate, vicarious thrill. Watching a particularly psychic pass or a flawless three-pointer, you often feel like the achievement is happening not just in front of but to you. Some of this has to do with basketball’s lack of padding and masks (you can see the expressions on the players’ faces as they work, which evinces a reflexive kind of empathy, makes it feel like theatre as much as sport), but it also has to do with the media ecosystem surrounding the NBA.

***

They don’t play the halftime show on most regular TV broadcasts. Instead, the 15-minute mid-game spot is devoted to commentary, advertising, or a seamless mix of the two. The closest you get to seeing the halftime performance on air is a tantalizing split-second right before the end of the break: sometimes they’ll play a montage of slow-motion clips from the game so far, and sometimes that montage will include a fleeting silent shot of the halftime show. This image, if it appears at all, flashes onscreen right at the very end of everything else: a shimmering, dreamlike flicker of a dance crew clad in sparkling gold robot costumes that dissolves into a razor ad before you’ve even had time to process it, the way a good dream evaporates out of your mind when your alarm rings, before you’re ready to let it go.

In the early weeks of my nascent NBA fandom, I watched every Raptors game on TV religiously but found it difficult to melt into the experience the way I had in the arena. A lot of this had to do with how closely all the ads encroached on the joy of the experience. At a live game, advertising is the literal wallpaper—scattered across the arena, printed on your tickets—but on TV, every time-out signals the beginning of a new barrage. If you’ve spent your life watching sports, you’re probably more or less inured to the pace and pitch of advertising in the broadcasts, but at this point the only sport I’d watched with any regularity was Jeopardy!. I was used to being gently whispered to about Gold Bond Medicated Foot Powder, not being yanked up by the collar and yelled at about drinks and shoes, cars and razors, The Keg and Real Sports, money and power and value and money.

After some research, I discovered that it was possible to access “in-game” streams through both legitimate and quasi-legal means: broadcasts of the game that showed you what was going on inside the stadium during time-outs and halftime. These feeds showed you the kiss cam and the dance crews and, most crucially, the halftime show. Pretty soon, I started watching every game I could this way—which is how my feelings about basketball grew from charmed interest to full-blown obsession.

Like a lot of good art, basketball draws you in by making you feel a surface-level excitement you don’t really need any training or background knowledge to access. This pleasure can make you curious about the game—about its rules and its players, about what kinds of people can do these kinds of things and how. And once you’re wondering, the league and the media outlets that cover it have millions of answers for you. Between profiles, in-depth interviews, highlight reels, practice footage, Instagram and Twitter and YouTube and podcasts and an endlessly updating feed of statistics, there is a near-infinite wealth of NBA knowledge for you to absorb and assimilate.

These two factors, up-closeness and in-depthness, work together in a cycle of exchange and encouragement that makes the NBA narcotically addictive. The more you know about a player—their life, their journey, their quirks and strengths, their effort—the more relatable they seem on an essential, basic level. For most basketball fans, investment and identification can become so fused they’re near-impossible to distinguish. Ask anyone what they love most about their favourite player and you will instantly learn something deeply personal about their desires, their values and their goals. I think often, for example, about what the poet Mikko Harvey told me a few years ago when discussing his love of D’Angelo Russell:

“DLo’s fluctuations remind me of the swings between self-confidence and self-loathing so characteristic of the writing life. […] To me DLo is the scout the universe has sent to find out if you can live a life steered by intuition and imagination and still excel in a hard system that asks you to exchange your sense of play for efficient, unending labor.”

This is how you can end up feeling intimately, personally invested in a millionaire’s ability to perform feats of physical strength and accomplishment you almost certainly never could. Stare at the game long enough and the distance between everything—players, league, game, court, self, other—begins to collapse. Everything becomes a metaphor for everything else, the league and your life each generating infinite layers of meaning for the other. Hard work, practice, repetition, desire: all these things are translatable. They live inside your life, too. In the best parts of professional basketball, the moments of perfect connection, all the news and money and surface-level noise seems to melt away and you know beyond a shadow of a doubt that the real core of the sport—the thing that calls you to it, keeps you caring—is something warm, complex, hopeful, essentially human. Realer than real.

There is, of course, an inverse version of this feeling. Sometimes if I’m watching a regular NBA broadcast on plain old live TV, there’ll be a moment when I feel shocked completely out of the moment, like I’ve been ejected from my seat or from my body. Most of the things that trigger this abrupt dissociation happen at the ad break: my five-hundredth viewing of an aggressively condescending bank ad, or the times when a player gets injured and the footage of them lying crumpled on the hardwood cuts abruptly to a commercial, inadvertently stringing the two images together like they’re part of one continuous entertainment, because they are. In these moments, I can feel the metaphor curdling, the warmth of the enterprise draining away.

This feeling, when it hits, is intensely familiar. I recognize it from a lifetime of enthusiastically consuming pop culture and living on the internet. It’s the queasiness that arises from deep, extended, voluntary contact with an institution whose fundamental purpose is to conjure a strong sense of engagement out of you so that it can eventually convert that feeling into cash. I get it when I think about the NBA’s tendency to quietly elide abusive or predatory behaviour by its players; I got it this past preseason with the Daryl Morey thing. It is the gut-level understanding that the distractions you turn to for comfort and hope and soothing escapist pleasure are directed by the same currents of power as whatever you’re trying to use them to escape. It is the feeling of having given over a large portion of your attention and your life and your love to something that is scaffolded, in the end, by money.

***

My love of the halftime show, like my love of the NBA, has everything to do with projection. I’m a writer who’s devoted the better part of her career to working on two books of prose poetry you could generously describe as “quietly received.” On balance, I have made no money from doing this—in fact, it has cost me more than I care to admit. It is difficult to explain this choice to anyone who has not made it themselves; most normal people think of poetry as antiquated, practically useless, and not very cool, and they are correct. (Some poets will try to tell you that poetry is “still important” or “more relevant than ever”; if they do this, they are trying to sell you a book of essays.)

However much I think I share with my favourite players—however I try to work their work into a metaphor for my own life—the truth is that the NBA performers I have the most in common with are the halftime acts. Like poetry, a lot of the best halftime shows feel brazenly out of step with time, fashion, and the logic of capitalism. Some are so far removed from contemporary trends that they seem to have time-travelled here from a pre-TV era. Like poetry, I don’t think many people pursue a career in Human Slinkying or quick-change artistry because they think it will make them incredibly rich or famous.

So why do it, then? Why devote your life to the endless practice of an art form that is at once unprofitable, unpopular and completely disconnected from the zeitgeist? Here I can only speak to my own choices. There are still kinds of literature in this world that you can make (some) money from writing: an author can sell a book with a strong narrative arc, or a clear thesis, or a sparkling world the reader can see in her head like a movie.

I love these kinds of books, but there are things they cannot do. It has been my personal experience—and maybe yours, too—that a lot of my strongest and weirdest and most vibrant feelings live outside of the limits of these more profitable kinds of articulation. They float beyond the narrative arc. The structure of a typical argument cannot contain them, and straight description never quite does them justice. They require a stranger kind of language, a vocabulary and a grammar untethered to the question of whether the largest possible number of people will find them immediately, pleasurably understandable and pay $20-40 for the privilege. When I am writing poems or reading them to an audience, in my most successful moments, I feel like I am participating in the centuries-old communal practice of building this vocabulary—like I am doing something small and significant and strange that reaches both forward and backward in time.

Is this all kind of embarrassing? Absolutely. Is it frequently ridiculous? You bet. There are so many ways in which this kind of effort can fall short or feel cringingly small, as awkward as watching a sweaty, shirtless guy balance shakily on two basketballs before a sea of empty seats. But it can also, occasionally, be transcendent. Think of how it feels to watch Red Panda, so completely immersed in her work that you can’t help but catch a contact high. This is the feeling of watching a real live human being connect with a practice that extends beyond this room, make a grand gesture toward something far greater and stranger and more complicated than the petty concerns of audience or paycheque.

And at halftime, you are not just watching this happen. You are watching it under the auspices of the National Basketball Association! A corporation whose every franchise is worth at least a billion dollars, whose productions are beloved by an unfathomably broad range of people all across the globe! Does that not give you a weird glimmer of uncommon, improbable hope? To me, the halftime show is a kind of Trojan horse—a secret, strange, and completely unique venue for performance art, hidden at the centre of one of pop culture’s most mainstream entertainment juggernauts.

It’s no coincidence that the show is also the longest stretch of any game that is completely untouched and untouchable by advertising. That’s why they don’t show it on regular TV—you can’t cut it with commercials, or layer them overtop. Its sustained existence inside the gigantic moneymaking spectacle of the NBA is a reminder that some kinds of art still resist commercialization, are perhaps even immune to it. It is proof that these weirder, smaller kinds of work can persist—flourish, even—in places that on the surface seem inhospitable to them.

The NBA halftime show is a living example of art thriving incongruously, impossibly, inside a system where almost everything else is optimized for maximum profit. It is a demonstration of a life’s work whose significance exists apart from the size of its audience, or their response to it. It makes a different kind of meaning, both inside and outside the rules. You don’t have to be a poet to love this. It is, like your life and mine, a flash of something small and strange and real inside the big, shiny machine. Something worth staying in your seat to see.