What were we obsessed with, invested in and plagued by in 2018? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the issues, big and small.

If there's one thing I know about recovering from a concussion, it's that nobody thinks they could possibly ever do it.

I know this because it's what every single person has said to me every single time I’ve told them the big long list of stuff you're not supposed to do during your initial period of "brain rest,” which for most people lasts about a week, but can take months for those with more severe injuries. The goal of this period is essentially to get both the amount of sensory input going into your brain and the amount of interaction you have with yourself down to zero for as long as you possibly can. You are trying to divert one hundred percent of your brain’s energy back to the recovery process, which means you can't listen to music or podcasts or audiobooks. You can't read, or watch TV or look at your phone. You can't cook at all, or clean without taking many breaks. You can't really go out anywhere, because all sensory input makes your eyeballs feel like they’re inflating in their sockets. You can't really talk to anyone for very long, or about anything of consequence. You absolutely can't drink or smoke weed, and you shouldn’t take CBD oil or any kind of painkillers or naps if you can help it. You can eat right and drink a lot of water and wake up at the same time every morning and go for short walks until you feel dizzy and besides that, basically, your options are to sit on the couch and stare at the wall, or to sit on the couch and see if you’re somehow any better at meditating than you were the last time you tried it. (Surprise! You’re not.)

Years ago, I had this friend—not super close, more of an acquaintance, really. We lived in Montreal at the same time, except that while I was drinking comically oversized bottles of 50 in the city's dumbest bars and writing poems about my complex emotional landscape, he was getting a degree in physics, and then a job at the school, and then one day on his way to work, into a horrific bike accident where he smashed his (helmeted!) head so hard on the pavement that the resulting brain injury lasted for literally years. I saw him when he was just emerging from the darkest part of his recovery—the black hole at the centre, the big rest—and when I asked him what he’d been doing since the accident, he just shrugged. Light jogs around the neighbourhood, petting a strip off the cat. I asked him whether he could at least catch up on his reading and he reeled off that long list of things he wasn’t allowed to do, and then I said the same thing that everyone says: Wow, I could never do that. Hubris!

I didn’t get my concussion in a bike accident, though when my brand-new manager at my brand-new job told all my new coworkers I had, I did not correct him. I got my concussion in the basement of my house, on a hot day in late August, while trying to locate the origin of the cat pee smell that had been lingering down there for weeks. I was bending down to check behind a box full of copies of the poetry collection I’d published in the spring, thinking about how funny and sad it would be if the cat had pissed all over them, and then when I stood up the top of my skull slammed hard into the corner of the concrete bulkhead that jutted out from the low ceiling.

I braced myself for pain, but felt something completely different instead: a powerful, shimmering nausea unlike anything I’d ever felt before, sweeping through my body in one intense wave from the top of my head right down into the arches of my feet. Like a natural disaster. I’m not sure how long I stood there, just letting the wave move through me in diminishing intervals like that, but I’m convinced that if you were watching me you could have seen my body cutting in and out like a bad signal. (Funnily enough, I had used this exact image often in that poetry collection, as a representation of an idea, and now it felt like it was actually happening to me. Hubris?) Weird, I thought, and then I stopped thinking at all.

Another thing they tell you at the clinic is that anxiety and memory both burn brain-energy at about three times the rate of regular thought, stimulating the exact parts of the organ you are trying to keep still for recovery purposes, and as such you should really try to avoid them wherever you can. So, okay: just sit on the couch for twelve hours a day with no distractions and a brain injury and do your best not to feel anxious, because feeling anxious will make your brain injury worse. Also don’t remember anything. No problem, right? I could never do that is the only logical response to this, even though it doesn’t matter whether you think you can, because you have to. The only people who think they can do it are nuns and monks and yoga people and the brainwashed; people tapped into some mystical dimension that requires total, rigorous, daily, full-body commitment to reach.

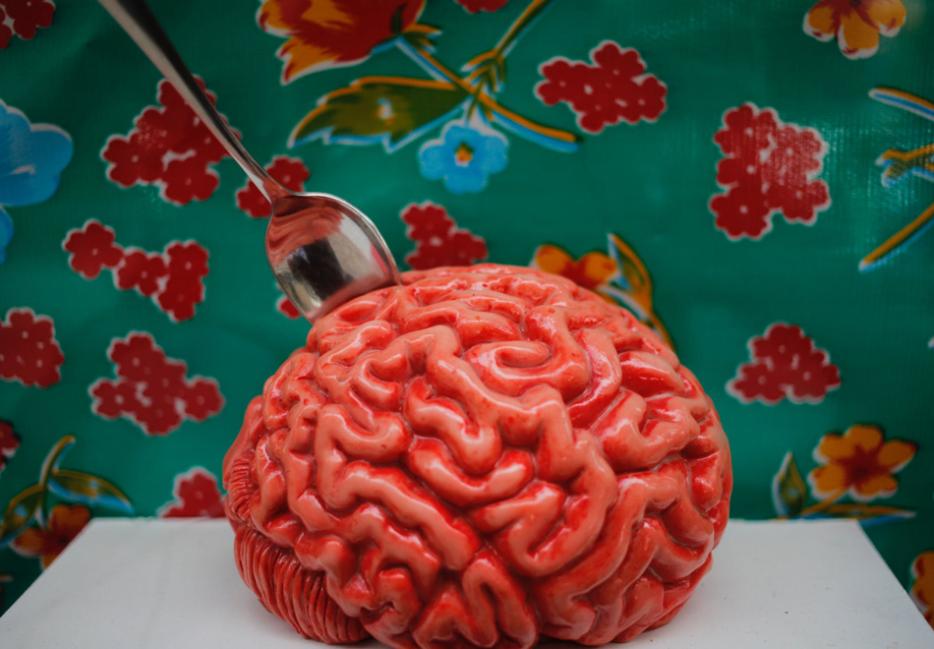

Concussion makes your relationship with your own mind hyperliteral, then turns it inside out. A few days into my initial recovery, I noticed this spot on the back left quadrant of my skull, about the size of a toonie. Most of the time the spot tingled in an ambient, white-noise kind of way, but if I tried to do anything too challenging—like, say, reading the IKEA catalogue for longer than four minutes, or thinking for ten seconds about all the money that was literally draining out of my bank account minute by minute as I sat there not working or moving or thinking—the tingling would flare into a hot pins-and-needles sensation that increased in volume until it burned so bright I would be literally forced to stop thinking at all until it died down.

When I described all of this to my doctor he just sat there nodding patiently, waiting for me to finish. That's blood rushing to the part of your brain you're trying to think with, he told me. Cool. You can use it as a guide, he said. If I felt a little tingling, I was doing something good for me, pushing myself just enough. Too much, and I knew to back off. Soon, this spot inside my skull became my only reliable metric for how much I should be thinking, whether I should stop. Recently, I’ve stopped being able to feel it; soon it will be entirely gone. I think I might miss it, though “miss” is also entirely the wrong word.

A friend once told me about this video he was obsessed with—specifically, the part where you can see the inner workings of the MTA control centre. The antique 1930s control panel, all those ancient levers and switches and wires. I like the part where the guy emphasizes that the whole thing is completely safe, just very, very old. That control centre, it turns out, is an excellent thing to picture when you’re picturing the inside of your brain. Idiosyncratically constructed, at once impossibly strong and idiotically precarious.

As long as I’ve been a depressed person, I have understood my depression primarily as an issue of crossed wires, chemical imbalance. My brain and my body are connected, and that’s why both of them feel better if I exercise and eat and sleep and drink water and take my pills at the same time every day. No big mystery. I say this all the time, and most of the time I believe it.

Still, though, I've never been able to completely let go of the secret conviction that some part of my emotional life operates completely outside of my body, and therefore completely outside my control. My most intense episodes of depression or anxiety can feel so full-body that when I am in their grip, it’s impossible to conceive of them as a glitch in my own chemical processing. In these moments, my emotions feel like truths about the world outside my body that have worked their way into my nervous system. It feels not just inadequate but foolish to presume they begin and end inside my body. They are not petty or small. They are a natural disaster.

But lately I’ve wondering whether there’s a third option: something bigger than my body that fits perfectly inside it. Like, okay: there’s this weird trick I can do with my memory. It’s been four months now since I hit my head in the basement, and though many of my symptoms have dissolved, I can still conjure those initial waves of strange, glittering nausea from the moment I hit my head in the first place. All I have to do is describe it—to myself or someone else—and suddenly, there they are, pulling all the way through me again, like nothing else I’ve ever felt before. I am one hundred percent certain that what I experience in these moments is not the memory of a feeling or the idea of it or a watered-down version cut with time and distance, but the actual exact same sensation I felt a whole four months ago, coming down through my body again.

Is this a glitch in my brain or is it time travel? Does it matter? Doesn’t trauma sear itself into your circuitry, and is that maybe a kind of magic too? Since I discovered I could do this, conjure the past into the present, I’ve found myself testing it out every couple of days—at my day job, in conversations, on the streetcar, in my bed alone—just to see. It feels perverse and queasy and inexplicably satisfying. It’s not a metaphor for anything. You never know all the things that your body can do, even when you’re sure you’ve felt each one. There’s always something new for you to learn from the interior.