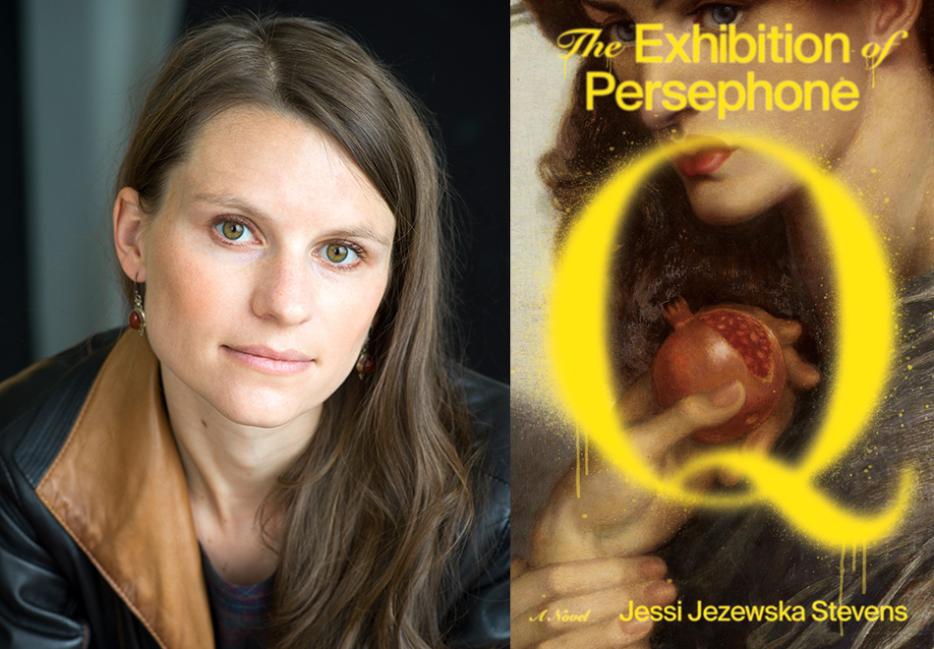

“Candid pupil,” writes Maria Edgeworth in An Essay on the Noble Science of Self-Justification, “you will readily accede to my first and fundamental axiom—that a lady can do no wrong.” This epigraph of Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s debut novel sets the tone: The Exhibition of Persephone Q (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux) will be a study in self-delusion.

Percy is pregnant and can’t seem to bring herself to tell her husband. She spends her nights drifting through a Manhattan recently devastated by 9/11, paying visits to her psychic and working for the self-help author down the hall. Fleeing questions of identity, her own violent impulses, and the future child known only as the nebula, Percy is unmoored until the day she receives a catalogue for her ex-fiancé’s art show. The titular exhibition—a series of digitally altered photographs that show the same nude woman sleeping on a bed as the objects around her, and the New York City skyline through the window, are slowly removed—acts as catalyst. The photos are of Percy, she’s sure of it, even if they fly in the face of everything she thinks she knows of herself. Her mission is now the ostensibly simple task of being believed.

The Exhibition of Persephone Q is an intimate, precise first novel, in turns funny and unsparing.

Alyssa Favreau: The novel opens with three simultaneous events. There’s a moment of sexual incompatibility, Percy’s unsuccessful attempt at asphyxiating her husband Misha, and a pregnancy. Why place all these incidents so firmly in the body?

Jessi Jezewska Stevens: I’ve been interested in the way that our frustrations with the systems in which we are embedded can manifest very physically, and possibly manifest more truthfully in a physical way than consciously, even. That perhaps there are certain moments in our lives where there’s more truth to the way we are expressing our confusions and frustrations in our bodily experience than how we might be able to articulate them in words. Certainly this seems to be true for Percy, who at least at the beginning of the book is especially in denial about her life, about her marriage, about becoming a mother. She’s going through all these changes, and so she’s retreating in the way you have to do to protect your delusions.

We learn much more about Percy as the story unfolds, and it is as if she’s learning about herself at the same time. Why separate her backstory so formally? It occupies its own section.

That comes partly from intention and partly the process of problem solving over the course of structuring a novel. It felt important to protect Percy’s ability to be in denial about the changes in her life until the end of the novel. In some ways that became a formal constraint. It also seems more truthful to the character at that moment, to have a bit of amnesia about the person that she’s been.

Thematically I was also interested in a kind of American condition that promises the right to reinvent oneself. For good and for bad. The idea that you can reinvent yourself is a cultural value, sort of a dream in this country, and it does rest on a great deal of forgetting. So I was also thinking of the ways in which that translates into a kind of willful amnesia.

You do seem particularly interested in the question of myth making, of creating or reclaiming narrative in one’s life.

In a way, I think of the idea of withholding Percy’s origin story until so late in the book as a second Exhibition of Persephone Q. There’s the literal exhibition in the book, in which Percy believes herself to be a woman in a series of intimate pictures. She is a passive character in that narrative, so I was thinking about having a second “exhibition” told in her voice. It’s possible that she could be trying to make meaning in telling that story. Or maybe another way of saying the same thing is that she reaches a certain breaking point where it becomes impossible to continue to be in denial about the person that she’s been, the people that she loves now, the mother that she might become.

Speaking of being forced out of a comfort zone, out of a feeling of safety, why choose a post-9/11 Manhattan as the backdrop for this story?

Questions of identity—of the narrative that one has of oneself versus the narrative others might have, and how tensions arise when those narratives come into conflict—are very central to the book. I didn’t set out to write a historical novel, but you are looking for those settings that amplify the questions you are interested in. I felt that on a national level, those questions of identity and being forced to answer the questions of “who am I?” and “do I recognize myself?” were questions that were very much present and urgent right after 9/11. I started writing this book during the 2016 election, when those questions—though they had always been urgent—came again very much to the forefront of national conversation. My hope was that in setting the book after 9/11 I would amplify those concerns, but in a way that felt very contemporary.

By including characters who are experiencing the internet in a very early, web 1.0 kind of way, were you hoping more broadly for the reader to bring a modern set of references to the story?

Absolutely. I hope that there are jokes to be enjoyed in returning to a slightly internet-illiterate narrator circa 2001. The contemporary reader has so much foresight when reading about Misha’s involvement in algorithmic advertising, right? We all understand today how this is going to fundamentally change not just commerce, not just the way we use the internet, but also another dominant narrative for what identity is: A set of algorithms.

To the extent that there is a bit of history of the internet in the book, it is very much written for contemporary readers. Misha doesn’t feel especially comfortable with his own involvement with online advertising. It’s quite likely that he’s the sort of person who’s going to sell off all his shares before internet advertising becomes the next big thing. His anxiety there is very much a bit of a joke for the contemporary reader.

It really endeared both characters to me, that their internet usage is so dated, and Misha’s worried about things like data collection and surveillance but has no idea how pressing those concerns are going to be in even ten years’ time. It was cute.

I know, and also a little bit sad too. When the Patriot Act happened we were all worried about phones being tapped, which was a real concern right? But then of course today we fast forward and now you send an email to someone and your banner ads immediately reflect the subject line of whatever you just sent.

What lessons can be learned from the mythological Persephone, the one that Percy calls “original Persephone”?

I was very struck by this idea of existing in two worlds, having a kind of split life or split self. That was what most interested me in building in the mythical references throughout the story, the extent to which Percy appears to be living a private reality separated from consensus reality.

It does seem like she’s in a dreamland, both because the routines of the city have been so disrupted and because she doesn’t sleep at night and goes wandering. There’s that hint of surrealism.

Right, and almost a kind of night world, or underworld, quality to the way that her sleep schedule flips at the beginning of the book in her effort to protect Misha from herself. Her impulse to pinch Misha’s nose and suffocate him a little bit is something she herself doesn’t seem to understand or recognize, so again there’s that idea of lacking self-recognition, or the unknowability of the self. There are latent capacities for violence in all of us. Percy buys knives, and to me there was a bit of a joke in the idea that she would be armed for most of the novel, and that she’s walking around the city on an errand to return these knives and gets very sidetracked.

Because of Percy’s passiveness, it’s interesting that she is actually capable of harming others. Maybe the isolation she feels is also a way of denying that she has the capacity to affect others.

Absolutely, and passivity itself as a mechanism for harm is something that is reflected in the pictures. Here is this inert figure on the bed even as there’s this enormous destruction represented around her in the room and out the window. That resonates with the harmfulness of Percy’s passivity in her own world.

There’s a real invocation of the symbol of the passive woman. From the long lineage of sleeping women in art to references to the second Mrs. de Winter in Rebecca, why were you drawn to that iconography?

I was aware of the danger of writing a passive female character. One of the interesting things about Percy to me was that she was someone without ambition. I would like it to be possible to write in a way where we can acknowledge these tropes, of the passive woman or the exploited woman in art, but also reclaim them. And even be able to reclaim them in an impish way, where I get to make jokes about it. I hope that the way these tropes come up in Percy’s character, or in the works of art that she encounters, that they aren’t presented passively, that we can see around them, into the idea that when women were represented that way, much was missed.

What does it mean to you that Percy’s main goal isn’t to have the exhibit taken down, but to simply be believed when she says that the photographs are of her?

I thought that was a much more interesting story. It was more interesting to me that Percy would eventually become more offended by the idea that people wouldn’t believe her—and in not believing her, would in a way be rejecting a certain narrative of self that she’s presenting.

The novel’s full of very disparate selves. There are the Percys that have her same name on the internet, the versions of her that Misha knows, that the fiancé knew. Is there ever a true self to come back to?

I think there’s a kind of a moving average, if you will. I do think that the self is not really a constant, and maybe that’s one reason why all of these different selves are reflected throughout the book. There can be a sense of home or of belonging, but I don’t believe that there is a real, static self.

Why have Percy undergoing such an important change? Her impending role as a mother casts a long shadow over the story.

From part one to part three, we perhaps feel slightly more confident in Percy’s ability to take care of her child. She begins to enter relationships of care toward others in a way that takes on responsibility. That shift to me relates to the idea of intimacy, of recognizing it in her life and reciprocating it.

It makes sense that this transition away from denial and selfishness dovetails with a move towards a greater intimacy, and the nebula becoming a little less… nebulous.

Yeah, there’s a scene where Percy wonders if she has perhaps lost Misha. She’s on the street and directly addresses the nebula for the very first time, and says, “It might just be us.” That’s also true, that her relationship with the nebula, i.e. her child, also forces her to recognize her own capacity for intimacy.

I read your essay “How to Buy a Rock” and was particularly struck by the line “if matters of the heart are constantly in flux then it seems to me one has to make the decision to stay in love again and again.” Do you see elements of that play out in Percy and Misha’s marriage?

Absolutely, I think that Percy makes that decision by the end. Misha would have every right at this point to choose otherwise, but seems to have made that decision once more. You asked whether there is a stable, or static self, and I’m not sure there is. If that’s true then between two people, if you are both in flux, you do continue to make the choice to be together as you’re continually becoming new people. I don’t find this to be a cynical outlook. I don’t want the book to seem ultimately cynical about love. I think that there can be something beautiful in that idea of things being constantly new.

How did the titular art show first come to you?

I have genuinely always disliked posing for pictures, or having my picture taken, so probably a little bit of my own dislike. It comes down to the question of what kind of event would force Percy to confront her own denial, or make it impossible for her continue as she’s been. She has an uncomfortable relationship to the pictures too in that there’s something exploitative in them, but she recognizes that there are also elements of tenderness. It’s a complicated response that arises from that tension between her fiancé’s presentation of her and how she sees herself. It is perhaps a gain in perspective.

Because of those complications, it makes it difficult at times to gauge how reliable Percy is as a narrator as she struggles to hold onto her life and her story. By the end of the novel, is there still that same uncertainty?

I felt very consciously that I was going to begin a novel as a mystery but not necessarily write a mystery novel, and not necessarily solve the mystery. The last line of the book introduces some ambiguity about even the realism of the story that was just told. To what extent does Percy feel like a made, or written, character, and to what extent does it feel like someone directly addressing the reader with a personal story? I was interested in that ambiguity especially because the novel, with this exhibition at the centre, is presenting the madeness of narratives. Certain choices that I made, such as the name Percy Q, draw attention to the fact that in some ways this feels like a very made up story, that it feels very crafted. Percy Q feels like a very made up name. When I’m thinking of the effect of those choices, of having a metafictional awareness, I suppose it invites readings that approach this as an analogy or a fable, or something explicitly made in service of some other aim, rather than someone confessing a true story.