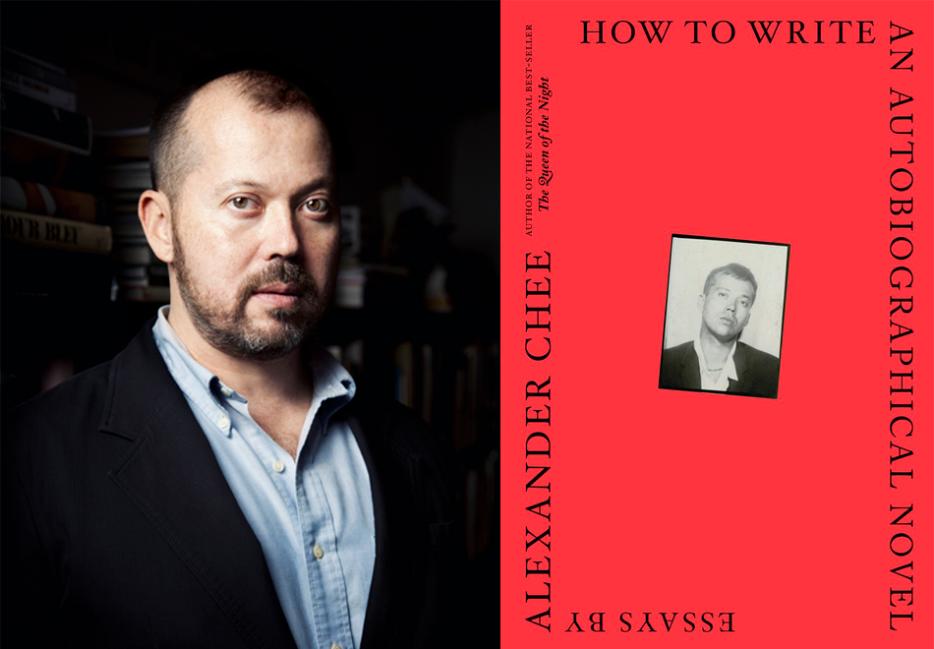

In his new essay collection, How To Write An Autobiographical Novel (Mariner Books), Alexander Chee addresses what can be one of the most challenging feats for a novelist: turning the focus inward. Growing up in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, Chee, who is Korean-American and gay, has often felt like an outsider. A contributing editor at The New Republic and an editor at large at the Virginia Quarterly Review, Chee is also the author of the novels Edinburgh and The Queen of the Night, as well as an associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth College. His essays explore the nuances and complexities of his identity—how he fits into the world, how he is perceived, and how he processes his experiences. You can feel Chee thinking on the page. And in sharing his life experiences, from marching in drag to growing a rose garden to becoming a Tarot card reader, Chee is deeply reflective.

Hope Reese: Some fiction writers will say that their characters simply "came to life." Is that different when the character is you?

Alexander Chee: It is different. And it's a little bit the same. It's very interesting to say, "Oh, the character just came alive," but the character is based on you. There is a way in which our own humanity is secured to us. That's part of why we read, and it's part of why we write. In a way, writing autobiographical fiction offers the opportunity for the writer to come into a different understanding of their lives, or come into some self-forgiveness. In the case of my own first novel, it allowed me to finally talk about some of the most difficult things that had happened to me—things I couldn't even name at the time—without feeling that weight on my chest. Without lying about it. It became clear that that novel prepared the ground for me finally remembering the things I put out of my mind. The reason why the novel couldn't have been a memoir.

How does it feel to have this nonfiction collection out in the world? Sharing some of the same experiences you write about in your novel in a different way?

I don't experience it that way, exactly. It's more like inviting the reader into the backstage area of the theater. There really isn't a one-to-one equivalency. The most vulnerable thing for me is admitting that these things happened to me. One thing that happened that I'm greatly heartened by is hearing from people who went through the scandal that this is all based on with me. And having them tell me how much they got out of reading the novel. That means everything.

You are a professional Tarot card reader and write in an essay that what you love about literature is also what you love about the Tarot. Can you explain?

The Tarot is like playing dress-up games with your life. You act as if the cards are strangers, at first. You may be apprehensive about what they could possibly mean to you. Gradually, as you look at the cards and apprehend the story of the cards, you apprehend the story they're telling you about your life. To me, that's a lot like reading.

You also write that reading the Tarot could be difficult because it puts you "in too close contact with the lives of others."

I have often read Tarot cards at parties. It became a thing for me to do at magazine parties, parties for different literary organizations. And—this also happens when I'm teaching—sometimes people will think that you know the answer to their question. That you're just not telling them. It's a psychological projection. So they can be a little bit intense about how they deal with it if they think you’re withholding an answer they need. But you're just telling them what you're telling them.

Sometimes I read for a couple and I can sense that they won't be together for very long. Especially if, when one of them sits down, the other one says, “are you asking about me?” That's usually a sign, on its own, of some kind of insecurity. I did correctly predict that after reading the cards for two people and spoke to the host of the party about them. They broke up later.

You spent a lot of time working in bookstores and have written that your literary heroes were once mainly women, often political. Who are your heroes now?

It's still true. The difference now is that I know many of them. I just got the new Deborah Eisenberg short story collection, which I'm over the moon to finally have in my hands. And now that some of these younger women who are political, I see also as those heroes. Like Franny Choi, the poet, a queer Korean-American poet. She's amazing. I see the ways that she's putting herself out there, creating community with other poets and other queer writers of color. She's really inspiring to me. Or Diana Oh, the Korean-American playwright. Last fall, when she was putting on a one-woman show, she put out a call for people to review her. Especially non-binary queer, trans, writers of color. She wanted reviews and wanted them from the community she cared about. As I was setting up the media for this book, I took a lesson from that. I'm negotiating what it would mean to put out that call in my own way. Those are two younger writers whose work I feel like I've been waiting for. It's incredibly exciting to me that they exist.

You joke in one of your essays about your editor trying to put you in this box—as "the first gay Korean American novelist." How do you feel about these labels?

There's ways that your visibility can be counted against you. It always feels like a way to get you to give it up. I did try for a while to simply insist on going the other route. So, for example, when marketing people were talking to me about Edinburgh they would say, "Is it a gay novel? Is it an Asian American novel?" And I'd say: "It's a novel." In doing so, the writer is trying to insist that they belong to the larger story—that they're not excluded from it in these subcategories. But at the same time, one is what one is. I belong to these communities. And I love them. I write for them. So I don't want to become invisible to them in the process. So it's a tricky dance. But we, as a community, have learned that the dream of potentially blending in is an old dream of the '60s. There are actually many different kinds of visibility, in ways that make more space for other people. Who may not have that identity, but it gives them space to create their own.

Annie Dillard taught you at Wesleyan College and you write about her influence on your writing. What did she teach you about how to become a successful writer?

She was very forthright about how she believed anyone who applied certain principles to their writing would improve as a writer. At this point in my teaching career, I can say that she's right. Talent, in some ways, is a little bit of a thief. It seems to offer you limitless access to opportunity—but even as it does, it reassures you that maybe you don't need to work as hard as everybody else. And that is the thing that will be your undoing. So that the person who steadily works at writing and gradually improves often becomes a writer more often than a talented person.

Having been on both sides—as a student and teacher of writing—what unexpected things have you learned from your students?

I mean, it’s an ocean. When I was studying writing, it was considered a bit pushing the limit—if not going over the limit—to write about politics in your fiction. And I never really understood why that was the case. It always seemed like a kind of middle class propriety, like, “Don't talk about money. Don't talk about sex.” If you followed those rules in writing, you would never talk about anything. And politics seems to have lagged behind more than sex—politics in fiction seems to be less represented than, say, sex in fiction.

It's something that I'm thinking about right now. I think it's more and more true that people are taking on writing about politics, the politics of their characters. I remember very much feeling like Mavis Gallant's stories, for example, were a place where I could see a writer working with, not just the intimate lives of her characters, but the intimate political lives of her characters. How the politics of their countries affected how they lived their lives, quite consequentially.

Since I can see how much this generation that I'm teaching is politically energized, I offered a new writing exercise where I asked them to write about the intimate political lives of their characters. And to think through even questions that seemed maybe a little outside of the ordinary—questions like, does your character vote? Are they someone who shows up for school board meetings? Are they just someone who votes on presidential elections? Do they not believe in voting at all? Like, where on that spectrum are they? Trying to get them to understand that these politics belong inside of the stories as much as anything else, as a way to know characters. Because it's very clear right now that, at least in America, people aged fourteen to twenty-two are having a massive political awakening.

You write that "only in America do we ask writers to believe they don't matter as a condition of writing." What do you mean by that?

It goes back to Boden talking about Yeats and saying that poetry doesn't matter. It's also, I think, something that is a very American attack on artists; rather than attack artists as people do in countries all over the world, attack the consequences of art—insist that art doesn't matter. So despite all evidence of the popularity of the National Endowment of the Arts, conservatives are always trying to kill it, even though it's an economic driver in many communities, because it supports much more than those individual artisans.

It's a little invisible to us right now, how much art is at the center of our lives. But at the same time, it's so visible—like when I'm on a subway in New York City at 8 or 9 p.m. and the car is completely quiet as people read on their way home, or on their way to work, or wherever they're going, and just being able to look around a New York City subway car and see book after book after book and the quiet concentration amid the life of the city, we know that the insistence that writers don't matter is something of a mistake.

If you had one more story to write before you die, what would it be?

I'm thinking about it now as I think about the rest of the work I want to be doing over the next decade, two decades. You know, I'm fifty years old, and I've got pages for about six different books, and ideas and all kinds of thought backed up while I was working on The Queen of the Night. There’s a story in this collection, something that grew in the shadow of The Queen—there's a novel that I've been putting off since 1994 that I have finally put up front, and I'm going to be working on that next.

If I'm going to tell a story before I die, that would seem to be the one.

You say you want your writing to "make you care." How have you learned how to make people care?

I think it rests on a mix of intuition and daring. Minimalism as an art form relies on the shared contexts that are usually dominant paradigms. And then you can hack them by changing the paradigm on the reader—have the reader work to figure out what you're talking about and then have them realize that they're not reading the dominant paradigm that they thought they would be in but in another one altogether. Usually by the time they figure that out, they're interested in going further.

When you write about characters who have been traditionally dehumanized by the culture, one of the most radical things you can do is renegotiate the reader's sense of their humanity for them. Take a look at how in historical fiction, the author is reintroducing the reader to a historical figure that they know well. So like, George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo, for example. The view of Lincoln that you've never met before except through him, through Saunders. The same tactic succeeds with characters from otherwise unrepresented communities. If you treat them like they're famous. It's a little bit of a joke about the process—which is to say, the reader thinks they know them in the same way that stereotypes and fame are related, essentially.

So you renegotiate their sense of what they object to, what the stereotype is. You present them in a way that sounds familiar and then the reader sees them differently, usually, hopefully.

You’re also interested in the effect of writing in a particular tense on the writer—not just the reader.

Yeah, just how the act of writing can actually impact the writer in ways you may not have expected. So James Baldwin actually talked about how using the present tense allowed him, in his memoir as he wrote it, greater access to his own memories. It sort of brought back the past quite powerfully. So it's not just me, but I think that's something that is a definite effect of that, when one is writing about events from one's life or events drawn from one's life.

There's also kind of a wonderful quicksilver feeling to writing in the present tense that I like. I feel myself in a kind of heightened state of imaginative awareness and capable of seeing more deeply into what I'm writing about. I almost wrote The Queen of the Night in the present tense, actually.

Or I should say, I did write chapters of it in the present tense and then rewrote them as the past.

But it did help me dig my way into her head more. Sometimes a different kind of authority ... It has that this-actually-happened authority and I've been writing about this phenomenon that Junot Diaz talks about quite a bit, which is called point of telling—where the writer is inventing not just the point of view of the story, but where the point of view was chosen. In other words, not just where one is telling the story from in terms of like a vantage point, like first person, second person, or third, this character or that character, but also like, when does that story come to you? How do you suddenly understand that you have a story whereas before you just had like the undifferentiated day-to-day life? So point of telling is a powerful choice to make in that context, because it offers up the reason why you're in the character's life.

You write about some difficult personal experiences, and have said that you need to make sure you can “descend” into the material while still coming out safely. How did you do that?

I mean, one way to do it is to commit to a process, where you say to yourself, "Okay, I'm going to write for X amount of time each day," or if you commit to a word count or something. That gives you a kind of boundary for stuff threatening to the identity of the person. The person, the writer is always trying to survive being in the same body. The writer has to give the person what they need and the person has to give the writer what they need ... a timeshare.

if you're writing about traumatic material, you need to pay attention to the way in which you are both writing about it—is it safe to describe the things you're describing? If you're in college, and you're writing about difficult family material—you should wait until you are financially independent of your family before you write about that, much less try to publish it. If you are financially dependent on them, you will inhibit yourself in ways you're not quite aware of. Or you might act out in other ways. And both might be injurious to you. Money is an emotional boundary. If you are reliant on money from people who have been abusive to you, it's a compromised boundary. It means that you're not safe yet. Sometimes the events you want write about are so vivid, so intense, so motivating that you think: I have to write about them. But you may not be thinking about the consequences of writing about it, and that certainly matters a great deal.

And another lesson you learned as a younger writer was to never take success or failure too seriously.

That's true also. The times I write about these difficult things, I do so with the idea that I can take the painful things that happened to me and turn them into something that can help other people. It's very gratifying to me that people are getting so much out of The Autobiography of My Novel essay. That was very painful to write. It was part of a group of essays I wasn't sure I would ever publish. It had been in my files for over a decade.