When Joy Press began working on Stealing the Show: How Women Are Revolutionizing Television (Atria), she felt that the golden age of female TV would be “a permanent advance.” That was before the 2016 presidential election. “Now," she writes, "It looks significantly more precarious and embattled.” That embattlement has led to a movement. If the importance of seeing women on screen, hiring women in writer’s rooms, and charging women with directing and producing was ever in question, it can no longer be ignored: “Time’s Up.”

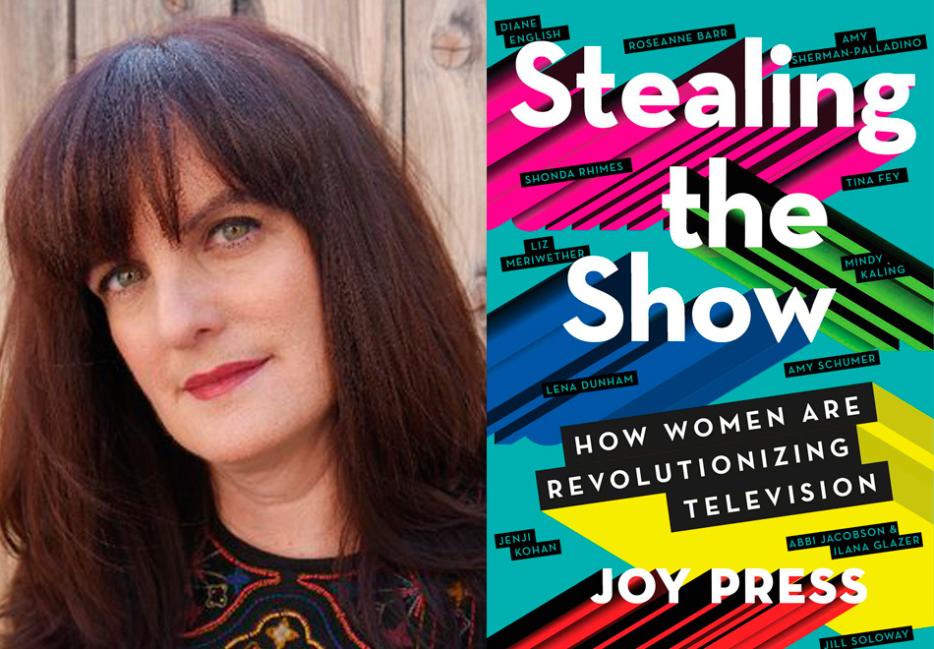

Press’s new book offers hope for the future. Stealing the Show is a wide-ranging tour of women’s impact on the entertainment industry, chronicling the a history of several key players who carved out critical roles for women on TV—roles that made waves far beyond the confines of the screen.

Stealing the Show traces the journey of characters from Murphy Brown, who riled up Dan Quayle and the Republican party by having a child as a single woman, to Broad City’s Abbi and Ilana, who “made a feminist statement out of toilet time.” The result highlights the obstacles women have faced in getting screen time and recognition—and how these women prevailed.

Press is a veteran entertainment reporter. She’s served as chief television critic at The Village Voice, entertainment editor of Salon, and editor at the Los Angeles Times. I called her to talk about single mothers on TV, why television still doesn’t do a good job with race, and the ending of Girls.

Hope Reese: You grew up watching The Mary Tyler Moore Show—a landmark television show with a strong female lead. What was the broad impact of that show?

Joy Press: I was really young when that show was on. I come from a pretty liberal family—my mom was a feminist—so I don’t think I necessarily understood how important and different Mary Tyler Moore was at the time. I just knew that there wasn’t a lot else. It’s odd how our brains adapt to what we’re presented with. I wasn’t sitting around saying “I need more shows about female experiences.” You gravitated toward the shows that amused you and meant something to you, and that was one of them.

It wasn’t until later, when I became a cultural writer, that I really thought intellectually about how little there had been. In college, we talked about Mary and Rhoda’s relationship as a touchstone, unique and wonderful. It was something people craved. Similar conversation happened around Sex and the City. And you realized there were only a handful of instances like this.

When Mary Tyler Moore was on air in the '70s, it was a turbulent time—but you say that it wasn’t fully reflected on that show. Is what's on TV today a better representation of our times?

I think we're getting there. There's a broader array of voices and perspectives engaging with the culture and the politics. You don't really realize you didn't have it until it appears. Recently, the burst of different female voices and people of color, you realize that, looking back, it was so barren. So lacking in these voices, so homogenous. There's a lot better reflection of our time today.

Is that partly due to a much greater range of spaces shows can air on as a result of the Internet, streaming, etc.?

The transformation of television has had a lot to do with this infusion of new voices on television. The TV industry is really massively fracturing. What's happened in recent years is the invasion of an increasing number of cable channels leeching viewers from the mainstream networks, and now you have streaming channels. I find it funny that we still call it "TV"—people are watching shows on their phones and their iPads.

The fracturing of the network system has had a lot to do with the changes we're seeing, in terms of who gets to be heard. When you had four or five mainstream networks, there were gatekeepers. For a very long time, they were mostly white men, and they were concerned with bringing in the biggest, whitest audience. Particularly focused on young men. They were focused on the bottom line. They didn't want to entrust a whole lot of money to female showrunners they didn't trust to make back the money, and to create shows the mainstream wouldn't be interested in.

Some of the women I write about manage to get through the cracks. Showtime, at one point, was trying to compete with HBO for high-end original programming. HBO positioned themselves as a bastion of male high-art with The Sopranos and super-macho stuff, in terms of the creators and the content. Showtime went the other way. They brought in all these female showrunners, like Jenji Kohan to do Weeds, and Ilene Chaiken to do The L Word. The streaming networks had done the same thing. Jill Soloway really made Amazon a sensation. Hulu is very open to female showrunners, and brought Mindy Kaling in after her show was cancelled on Fox. That's been responsible for a lot of new openness.

You chose a handful of specific shows in your book—from Murphy Brown to 30 Rock to Girls—to illustrate the ascendance of women in TV. How did you pick these? Are there some you left out?

The hardest part of the book was trying to figure that out. I was originally thinking about it in terms of a survey, a broad take, but that doesn't make for a great narrative. For many of the women in the book, there's a thread that runs through. Many of them have worked on each other's shows, so there's a lineage, and I connected the dots. Some of it was picking things that exposed some element of the culture.

I started with Murphy Brown and Roseanne because they came out in the middle of the culture wars in the '80s and really became very central to the culture. They had very, very different female characters who captured the public's imagination. Murphy Brown captured the vice president's imagination. For Shonda Rhimes, that was true to a different degree. And actresses like Lena Dunham and Amy Schumer became focal points of the right wing, again. It was an eerie thing—I wasn't expecting that.

Can you expand on Roseanne's significance? How she symbolized the working-class, which wasn't often seen on TV? Even today, we're often lacking that perspective. Girls, for one, has been criticized for representing a small, privileged slice of a younger generation.

Roseanne was extraordinary. There had been shows with working-class characters, like All in the Family and The Honeymooners, but Roseanne showed a level of realism that people were incredibly drawn to. They didn't play politics. They were of-the-moment and they embedded the struggles of the time in their characters and plotlines. People appreciated that. There was nothing preachy about it. But it was fairly radical—there were attacks on birth control at the time, there were certainly attacks on female reproductive rights, attacks on welfare, gay rights. Roseanne very steadfastly took on all of those things in a way people could relate to.

Murphy Brown was quite the opposite. She was elite, she was at the pinnacle of her profession, she was mirroring a lot of the problems women in the media were having, in terms of hitting a glass ceiling. She was not going to take any bullshit. In a completely different way from Roseanne, but incredibly inspiring and refreshing. Having the two women on air at the same time was fascinating.

Girls made clear from the beginning that these women were privileged. There was never any sense that the writers of the show did not realize that—in fact, they often made fun of it. It was baked into the show that these women had huge flaws. Lena Dunham's character was so clueless and so flawed in so many ways. And it's not that there haven't been working class women on television.

SMILF and Fleabag come to mind...

SMILF is new, and that didn't come out until the book was finished. Fleabag is fantastic. Part of the problem is that when you only have a few female voices, or a few black voices, it puts a lot of pressure on them. There was a strange pressure on Girls to be representative. It's never a problem for men. Men are allowed to be whatever quirky thing they are. Some of the pressure on Girls was fair. But the more female voices there are, the less pressure there is on each one of them to anything other than tell their story.

Several of the female TV characters you write about—Murphy Brown, Liz Lemon, Hannah Horvath—become single mothers. How have reactions to this changed over the last thirty years? What does that teach us about cultural norms?

The reactions to single moms on TV has changed, and give us a good glimpse of what the arguments and panics are at whatever cultural moment in time we're in. Murphy Brown's creator was not expecting a huge backlash. There had been a couple of single moms on TV shows before that. There was a big battle at that point over family values. This was something that the religious right, the conservatives, had taken up as a huge issue. There was a big battle over "welfare moms." Murphy Brown was a very convenient, very public figure. A fictional character who stood in for a folk devil, who represented everything the religious right hated. In fact, Murphy Brown, the character, was regularly wrangling with Republican politicians and the religious right. Dan Quayle was literally being mocked on the TV show. It was a perfect storm. How better to get your ideas across than through this character, who everybody is familiar with? She's an obnoxious, forthright, super liberal, hard-charging feminist. The right decided to run with it, but it didn't work out well for them. The show continued to be popular. There were a lot of single women in America, a lot of working women, a lot of single mothers. People happy with the culture changing. So the gambit to demonize Murphy Brown spoke to the base of the Republican Party very effectively. It set fire to the idea of the cultural elite, pitting Hollywood against America.

30 Rock played everything for laughs. It didn't have the kind of realism that Murphy Brown had. Liz Lemon was, at best, a pretty iconic figure. And certainly a lot of people identified with her. It was fantastic to have such a "schlumpy" character—a workaholic character who ate bad junk food, often shot herself in the foot. You wanted Liz Lemon to be happy, but you weren't worried that she was going to become any kind of realistic figure.

Lena Dunham, to echo Murphy Brown, was already a favorite whipping girl for the right wing. Deciding to become a single mother was exactly what they would have expected.

I, for one, am a huge Girls fan—but had a tough time with the ending.

I was surprised by the ending. I'm not sure it left Hannah in a place we would have wanted to see her. But I do think the show very consistently found ways to make Hannah, and the audience, uncomfortable. There is nothing that makes us more uncomfortable than the idea of a not-good mother. It's something Roseanne played with, all those years ago. When you go back and watch the show, she really is a good mother—but she wasn't the perfect TV mother of that era. There's a sense that Hannah may be as incompetent a mother as she was an employee, a teacher. She was not a very good teacher. She had the potential to be a good teacher, but she couldn't control her impulses. So you have the sense that she may be that way as a mother.

Where does that leave us? It makes us wonder what our expectations are.

Are there topics that are still taboo on television?

I don't know if there are topics that are still explicitly taboo. When you talk about something like abortion, it is no longer taboo in that quite a number of shows have dealt with it. But Shonda Rimes talked about the difference that she experienced when she initially put Gray's Anatomy on the air and wanted to deal with abortion very early on—and realized that was just not going to happen. But still, we see it. It's treated with kid gloves.

Race is still not dealt with very sophisticatedly, for the most part. It's changing a little bit. Having more writers of color in the writer's room and more showrunners of color is going to help. It's often just clumsy or it's avoided.

All of those things are going to have to change. There will have to be more trans writers in the writer's room. I don't think that shows necessarily avoid those topics, but people don't know what their blinders are, what their biases are. These things are not taboo, but could be dealt with in a more sophisticated way.

Are there women-centric shows that can undercut a feminist message? What about Sex and the City? It was groundbreaking, represents empowerment through female friendships—but is also blatantly materialistic, and the driving force for many characters is finding a male partner.

Shows by women are sometimes self-defeating—because women are often self-defeating. I consider myself a feminist, but I'm sure I do things that undermine myself all the time. There isn't a litmus test.

Sex and the City was an interesting case for me. I had really mixed feelings about it at the time. I loved it. And I also, at the time, had a lot of problems with it. I grew up in New York, and I felt like I would never want to actually hang out with people who went to those clubs and bars and shopped in those stores. But I was also frustrated by the way that it was increasingly about the romances. There was friendship, but you didn't see them much in their working lives. It was fixated on who was going to be the partners, and the complications that stemmed from the men.

You take what you can from television shows. I never expect all TV shows to be perfect. In fact, so many of the shows created by female showrunners are very ambivalent portraits of women's lives. Fleabag, for one. It's a very disturbing portrait of a woman in some ways. Very few of these characters are role models.

So, Broad City was compared to Girls, and generally, people were celebrating Broad City and using it to put down Girls. I adore Broad City. For the most part, it's a bright, sunshine-y, psychedelic, awesome time. It's female power, silliness, even the awful stuff is treated with such joyousness. Of course, you're going to feel all glowy after you watch it. Girls is a very different experience. But there's room for both of those things. Crazy Ex-Girlfriend—there's no way [Rebecca Bunch is] a model human being. She's just a human being. And [Issa in] Insecure—she's a complicated human being who's making mistakes.

I just made a timeline of shows created by women. In the beginning, there were a few every decade. And then in the 2000s, there were one or two every year. Then in 2015, it was exponential. It's crazy.