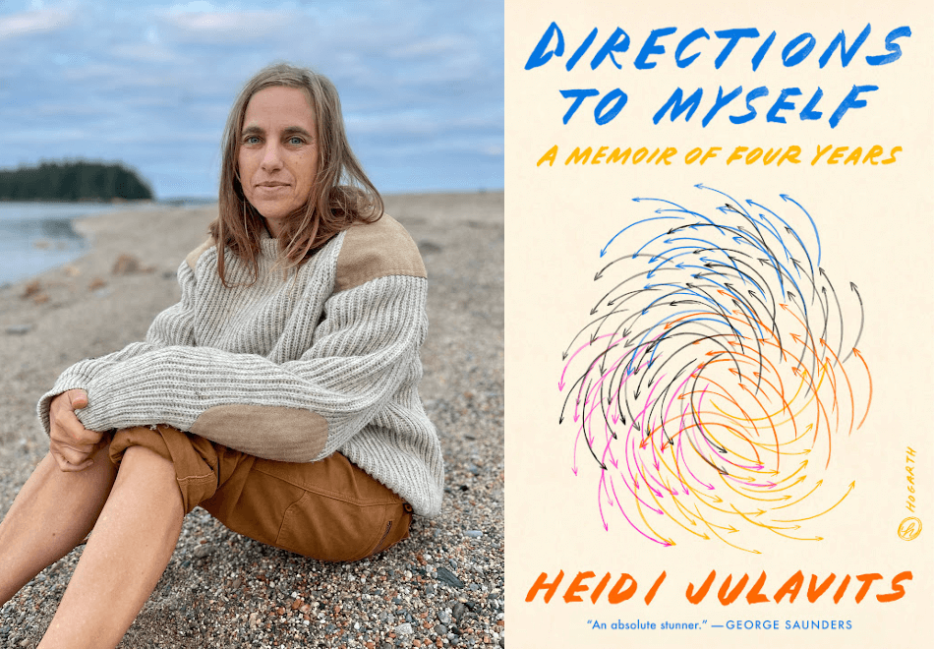

“Points of orientation aren’t constant,” Heidi Julavits writes in Directions to Myself: A Memoir of Four Years (Hogarth). In this latest book, Julavits uses this kind of thinking to probe into how, exactly, to navigate a life. What depends on luck? How do we move from the past to the present? How do we prepare for the future? For Julavits, author and co-founder of The Believer magazine, this question is especially pressing—she’s in a transitional period, and her relationship with her growing children is shifting. “Before, I was accumulating experiences,” she writes, but “now, on certain days, it feels like all I’m accumulating is the experience of losing the experiences I’d gained.”

Directions to Myself “represents more of a literal middle-age,” Julavits tells me, “and an interior reckoning.” Exploring the relationship of physical landscape to our inner terrain, Julavits intentionally does not name locations in her book, though she spends a lot of time on the water—in fact, this book was inspired by A Cruising Guide to the New England Coast, a book she discovered that showed how to use what she calls a “narrative map” for orientation. In Directions to Myself, Julavits uses navigating the sea and land to make analogies about her perception of the passing of time. “The rower faces backward and cannot see where they’re going,” she writes. “Instead, as they row toward their destination, they must perpetually contemplate where they’ve been.”

Julavits is the author of several books, including The Vanishers and The Folded Clock: A Memoir, and has recently written for The New York Times Magazine and the New Yorker. She is an associate professor of writing at Columbia University, and it was near the end of the semester when we spoke. Julavits wore headphones because of some nearby construction that made her feel like she was “living in a psych experiment right now,” she said. “The city is doing its best to push me out.”

Hope Reese: Your previous memoir, The Folded Clock, had a specific structure that you have said made it easy for the book to unfold. What was your idea for how to set this book up?

Heidi Julavits: This was a very different book in terms of how it came to be. The Folded Clock just came to me. I literally wasn’t even intending to write a book, which I have to say is the best way to write a book. I don’t think you can fool yourself twice, but I enjoyed doing that. That structure was, “I’m going to re-create my childhood diaries only insofar as this is how I started every one of them off.”

[Directions to Myself] took a lot of different turns. I started writing it when my son was really young and the Columbia campus had just started to erupt. It was initiated by Emma Sulkowicz’s “Carry That Weight” performance when she carried her mattress to school every day in protest of the fact that the university did not expel the person who she reported sexually assaulted her. Originally, [the book] was almost like a polemic. This was pre-#MeToo, pre-Trump, pre- a lot of things. I was talking a lot about the stuff that concerned me as a person raising a son, because it didn’t feel like it was being talked about at all. It was very provocatively called “How to Raise a Rapist.”

Then everything happened: #MeToo happened, Trump happened, and suddenly all the things that I had been writing about were being written about a lot. The conversation was moving super quickly, right? That conversation was moving at a speed that a book, at that point, didn’t feel like it could kind of keep up with—at least the one that I had begun. I had to take a step back and think, “Okay, well, what is this book about?”

As I started to shift gears, I realized it was tapping into a lot of the things that The Folded Clock tapped into—loss and sadness and these quotidian things like trash. You know, I write about trash a lot in this book.

As I was trying to sort my way through all of this, these feelings that I needed to continue to hammer away at, I found this book that had been around in my parents’ bookshelves when I was a kid. It’s called A Cruising Guide to the New England Coast. A book of stories. It’s, like, story maps about how to get to a place. They don’t give you actual maps, they use these temporal landmarks like a barn, or a rock and say, “Leave the rocks at port and aim your bow toward Mr. Baker’s barn.” I found myself completely transfixed by this idea of a verbal, narrative map, to tell you how to find a place or person.

That was the formal discovery that allowed me to organize all my thoughts.

In a conversation with Interview Magazine in 2012, you said “I don’t think out the plot ahead of time.” When you were conceiving of this, did you know how it would end?

There are probably hundreds of thousands, not an exaggeration, of pieces on the cutting room floor. I have documents, documents, documents.

Once I discovered the narrative form, suddenly all these things that I had lost, even three or four years ago, dumped them in some scrap folder somewhere, I would go searching for them. I’d go back to look for something, like, “Oh, where was that thing I wrote about the Norwegian family that went on vacation in the ’30s? Maybe that’s relevant now.” It was almost like going through a storage box in your closet where you have all these old clothes that you haven’t worn in forever, and think, “Maybe some of these, I don’t know, maybe I could still wear these!” So it became a kind of different writing project. In a sense, a lot of it was written already, it just hadn’t been organized properly.

The other big change that I made is that when I first decided to write it as directions, I wrote in the second person. The whole book was in the second person. And now it’s in the first.

That’s a lot of work!

Yeah, it was a lot of work. But I’m here to be that spokesperson for doing a lot of work and coming out the other side.

You’ve written in different genres—are you more drawn toward memoir and nonfiction these days?

I am interested in nonfiction, but I’m not a reporter and I’m not a researcher. And maybe I should try to become one, but what interests me more is trying to arrange things that might not seem as though they should go together—to put them together and then see how they echo off of each other.

Years ago, I ended up buying the estate of a dead French actress off of eBay. She’s been coming out kind of regularly in my last couple of books. I’ve been trying really hard to figure out, like, why? Where does that belong, or how? What does it say to me? Why am I compelled by that? Why did I buy all of her clothing? I think nonfiction interests me as a sort of juxtapositional art form.

That said, I want to write another novel. One is percolating, and I think about it all the time. Interestingly, I don’t feel like I have learned enough yet about myself in terms of what interests me now—structurally, and even stylistically—to go back and do it yet.

Your next book, Altitude Sickness, is a series of essays. How did you come up with the theme?

[It also includes] medically assisted suicide, end of life options. There have been some very dramatic instances, both with friends I know and people in the community in Maine where I live, where couples have decided to jointly end their lives because of degenerative health things.

Over the course of writing these books, what have you learned?

You need to perfect the entry point. That’s why with The Folded Clock, “Today I” was the entry point that unlocked everything. Now I’m very aware I need to set up the parameters so that when I enter that space, I can’t go most places, but the places I can go are going to infinitely yield.

In writing Directions to Myself, what were the biggest challenges? Are these different from your challenges in the past?

The really big challenge seems to be the challenge I’m accepting for everything that I’m writing: it comes with a great deal of risk. I’m writing a book that is about my son, who never is named—but, whatever, the internet. I’m trying to represent people who I love, people I respect, people who I don’t want to hurt.

It’s obvious on one level why that would be tricky. But on another level, it requires such precision and care. It requires me, as a writer, to look at every word and every sentence and think about all the ways in which it can be read. In ways that I intended, in ways that I don’t. I find that relationship to writing makes it feel a lot more trenchant, like it matters.

Many women (like Carmen Maria Machado or Maggie Smith or Erin Keane) have recently written about people in their lives—such as partners or family—who are currently living. Do you think there’s anything new about what’s going on now?

I do think it’s been going on since people started nonfiction. I’m thinking about, obviously The Goncourt Journals—they weren’t necessarily thinking that those were going to be public. But, you know, people have always been writing about other people.

I think what’s more interesting is this particular familial relationship—the mother-child. The person that kept coming to mind as I was writing this was Sally Mann, the photographer. It made me think about the ways that mothers, in particular, are vilified—in the same way that Sally Mann was.

Let me back up. Sally Mann was seen as unethical, immoral, for featuring her children in her art. Now more people are questioning that judgment, or wondering how to turn this really quite all-consuming love and attachment and fixation into art without necessarily buying into a double-edged implication.

One implication is that it’s “women’s concerns.” It’s domestic. It is not art-worthy. Plenty of people have been poking at that for a while now. This is not that new, but it’s sort of new. The other side of it would be questioning what counts as good, responsible caretaking. What’s the violation of that?

You write about the unpredictable nature of life, and the role of luck in our lives. In your own personal life, or in your career, what role has luck played?

I was set up to be lucky, right? Some of us start out in socio-economic spaces where luck is going to come your way quite a bit more regularly. I didn’t have to fight my way up to that space where, you know, luck was zooming by on the highway all the time. I just had to let go and step in the way of it.

I’m a white woman born to college-educated parents, and I went to a college. From the start, I had the opportunity to be lucky. Maybe it says something about me that when I’m asked this question, I don’t think, “Oh my God, something lucky and good happened to me!” I end up thinking about luck in terms of, “I luckily evaded something terrible from happening”—which is maybe a very pessimistic way to look at luck. But on the other hand, I’m talking about surviving. I’m talking about, in one case, not getting raped. So, for whatever reason, I have put luck and survival a little bit together in my head.

When you launched The Believer twenty years ago, you wrote about the state of criticism. Since then, how do you think criticism has evolved?

I just kind of stopped reading it. It’s not because I’m not interested in it. I have so little time to read because of teaching that I just spare those moments for reading books.

Back then, I spent a lot of my energy paying attention to the magazine environment and the critical environment and everything that was happening and trying to keep The Believer relevant and responsive to the changes that were happening. Our big challenge, back in the day, was to sort of transition from a space where there was dwindling real estate in print magazines, but then suddenly the internet happened. So, how are you perceiving lack? How does your perception of what needs to be there—how do you make it be there? It was something that I had to pay attention to for so many decades—so when I was not the editor anymore, I was actually really relieved to be able to take a bit of a hiatus.

One of your points was that it’s not books, but authors and careers that are reviewed. How do you imagine that this book will be received, in terms of how it fits into the overall arc of your career?

Oh, my God. I mean, I don’t know. I also worked on Women in Clothes with Sheila Heti and Leanne Shapton, and I was recently explaining the feeling that I have right now in clothing terms. I was like, “I kind of feel like I agreed to leave the house wearing an outfit that doesn’t make me feel protected.”

A lot of the books that I have been writing up to this time in my career, they’ve been funny. Earlier novels were maybe a little bit arch. They had big ideas. This time, I wanted to write a book that was just emotional. I have had a bunch of people tell me that they cried when they finished it.

Not that I want to make people cry, but, in the end, the thing that kept bringing me back, even though I was having such a hard time cracking this book, is that there was a really intense emotional reality—in the sense that I felt like I wanted to try to articulate it or represent it, or maybe just live in it and see what happened.

As a result, I feel like if it’s raining out, I don’t have my raincoat.

You write that you’re at a place where you’ve stopped accumulating new experiences; now you’re trying to hold on to the old ones. What’s been happening?

It’s this transitional space. This super embodied, fleshy, physical space that I had been inhabiting, intellectually and otherwise, I feel like I’m transmitting right now—I’m not bringing my fleshy mind into it—I’m transmitting emotion, in a sense. It’s a recalibration of input and output.

This speaks to the fact that there’s been a lot of output as a human trying to raise two small other humans. There’s obviously so much input, but it can sometimes feel like it’s more output. Now, suddenly, I don’t need to output as much anymore. They don’t need as much from me. It can feel like a really strong wind is blowing at you, you’ve been leaning into it to make sure you don’t fall over and then the wind just stops and you fall on your face. The forces around you have changed, you know?

What I’m trying to figure out is: What’s the new wind?