For reasons unknown, the public success of young women writers seems disproportionately liable to provoke pronouncements that they are the voice of a generation. Taken literally, the implication is absurd. If, tomorrow, aliens were to descend and encounter the platitude in a research binge through back-issues of general interest magazines, they might assume that demographic groupings of similarly-aged people lie in desperate wait for a singular mouthpiece to proclaim their shared experience and, once located, heave a sigh of collective relief. Maybe there are worse things for the aliens to believe, but that’s not the point.

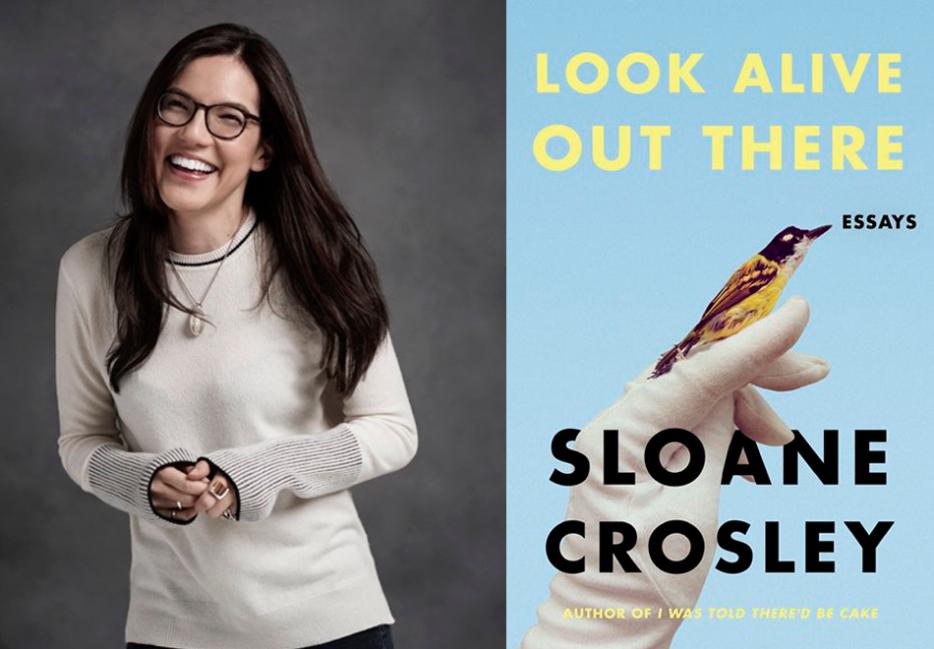

Author Sloane Crosley has written around the designation, but she hasn’t avoided it. Her 2008 debut collection of personal essays, I Was Told There’d Be Cake, prompted one critic to anoint her, specifically, a voice of “the mall-rat generation,” which, as typical for pop sociological shorthand, manages to be both momentarily evocative and something of an unintended punchline. In the ten years that have followed, Crosley has drawn a panoply of pronouncements and comparisons; author David Sedaris, in whose trenchant wit and undercurrents of empathy many of Crosley’s readers have found a parallel, calls her “relentlessly funny.”

In the past decade, Crosley has released a second essay collection (How Did You Get This Number) and a novel (The Clasp) and secured her position as a voice for, if not a generation, maybe a certain type of Manhattanite that is prone to the wackier effects of urban situational alchemy. In Crosley, the particulars of mystified New Yorker neuroses—inevitable when one is working all the time while surrounded by people who are neither friends nor kin—press up against the quotidian banalities that lifestyle publications have decided call “adulting.”

Crosley’s third and brand-new essay collection Look Alive Out There (HarperAvenue) surfaces the author’s trademark propensity for fish-out-of-water knee-slappers and their concurrent interrogations of belonging. Several essays detail the intimacy-sans-protocol of sharing space in a city; three, in particular, concern the dynamics between neighbours in turns frustrating, poignant, and sad. “Part of what’s interesting about living in New York is how much business you can choose to have with people who are absolutely none of your business,” Crosley writes in “Immediate Family,” an essay that recounts the author’s attendance of a shiva in her apartment building.

We spoke with Crosley about Look Alive Out There, generational designations, and states of coexistence.

Kelli Korducki: This may seem like a random question, but, what generation do you feel like you belong to?

Sloane Crosley: Oh my god I love this question! Not the Millennial one!

You’re not? Interesting!

Well, I’m not! I think it’s a fact. I was born in 1978.

But like, toward the end.

Toward the end of 1978? I mean, I was born in August. But I don’t think it’s a dividing-by-months, splitting-hairs situation. Am I X? I think I’m Gen X.

There’s been a lot of debate about this over the years. I thought it would be interesting to see where you see yourself, because everyone I know who was born between the late-’70s and early-’80s answers this question differently.

One of the pre-publication reviews of Look Alive Out There used the term “Millennial” about me and I was laughing because, like, I’m almost forty!

Doree Shafrir wrote that Slate piece years ago about how people born during the Carter administration should be called “Generation Catalano.”

Oh my gosh. That’s so good. The whole generation thing, it can make you feel a little bit trapped… I can’t believe I’m about to voluntarily bring this whole thing up, but when the Me Too list—the shitty men in the media list—came out, it was very interesting to survey the reactions among women who were exactly my age. It seemed like, in general, we were sort of trapped in a purgatory of reaction.

Sometimes, it seems like my response tends toward, “That’s the reaction of a twenty-five-year-old,” or, “That seems like the reaction of someone who is hyper sensitive or hyper politically correct.” But then the second you feel that, the other nightmare is—I don’t want to align myself with the Angela Lansburys and Chrissie Hyndes of this world, who have gone on record saying horrible things about that. I think that experience has made me think a lot more about my generation than I have in a long time.

I think a lot about how much the conversation has shifted since I was in high school in the early-2000s.

It seems like the past, crimes or trespasses perpetrated were written in invisible ink, and this moment has made the ink visible. When Me Too first started blowing up, I thought, "I don’t know that I’ve ever been put in an uncomfortable position or sexually harassed!" And then I started thinking… and the ink sort of came into view. It’s great to think about going forward, in terms of where the lines are.

One thing that made me think about age, and where you situate yourself, is that you were in your twenties when you wrote your first book.

There was a weird delay with the release of I Was Told There’d Be Cake but yeah, I was twenty-seven. A child!

An actual infant! Obviously, the culture has changed in some key ways and you’re in a different phase in your life—in one essay, you write about freezing your eggs!—but I’m wondering whether anything’s changed in terms of your approach to writing?

Not much. For nonfiction, I usually begin with a goal or an end in mind—something will lock in where I think, “I have to write about it.” And it’s always something surprising. I’m trying to think of an example from the new book… okay, so for the California essay [“Take the Canoe Out”], it wasn’t until what is the very last moment in the essay, when I got a package in the mail, that I knew I had to write about it. Even though there were plenty of adventures that led up to that.

There’s a shorter essay where I’m in France [“Brace Yourself”], and I’m standing in the middle of a large lawn and three women walk away from me at different paces. One is pacing on the phone, one goes marching in and out, and one goes to answer a phone call—usually a moment will lock in like that, and that’s sort of the moment I’m working toward when I write. Or also I’ll picture the ending. Sometimes I’ll picture the last line perfectly and I just have to get to it.

My goal, which isn’t always successful, is to try to take the training wheels off of essays, because I tend to have a roundabout way of getting to things. Sometimes that’s charming, and sometimes it feels like a diversion. My goal is always to figure out what’s the best way to make my point as quickly as possible while also entertaining people.

Switching gears a bit, the book has those two longer essays about your dynamics with two different New York neighbors that I read as kind of a pair: “The Grape Man,” about a neighbor you’re fond of but don’t really know too well, and “Outside Voices,” about a neighbor you don’t know at all who has become your waking nightmare. Did you consciously set out to offset each of these stories with the other?

It’s interesting, the have situational similarities but they weren’t conscious. I’ll often pair a shorter essay with a longer essay that’s thematically similar. There’s the smaller essay I have [“You Someday Lucky”] about my coworkers who are obsessed with the [number-based personality diagnosing system] Enneagram, and I say they’re from Boulder which is kind of the Bennington of the west. And then in the next essay [“Take the Canoe Out”] I fall in with these pot-smoking hippies in northern California. They really have nothing to do with each other, and yet they have everything to do with each other.

But those two essays, “Outside Voices” and “The Grape Man,” I tried to separate them as much as possible so that I could let each one breathe. What I like about them is that they’re negative images of each other. It’s how beautiful living in close quarters can be and how hellish living in close quarters can be, and they’re sort of the southern and northern oracle of that theory.

It seems to me that a lot of your essays grapple with, either directly or not, the effect that living in New York has on the way you see yourself and your place in the world. Is this something you’re conscious of? Am I totally projecting?

I have the same relationship with writing that I have with New York, which is that I’m just ever so slightly outside. I grew up in White Plains, which is a commuter town thirty minutes outside of the city. So, while I’m not from New York, it’s not exactly the same as moving to New York from Florida or England. It’s not Goodbye to All That, where she genuinely can’t identify the bridges. I’m invited to the party, but I don’t feel totally comfortable. But you have to be slightly uncomfortable to be able to walk down the street and notice things. It’s hard to observe something if you’re the life of the party or the white-hot center of it. In that way, New York informs my writing.

But you also have a genuine knack for getting plopped into totally foreign scenarios, whether scaling a tough Ecuadorian volcano as a novice climber or playing yourself on Gossip Girl.

I really milked that cameo for all it’s worth, huh?

You know, I tried finding it on YouTube but couldn’t.

Every once in a while, it’ll pop up from a stranger, somebody who decided to re-watch all of Gossip Girl and they’ll notice it and tweet at me.

I’m going to find it eventually.

It’s exactly as described—one might call it, over-described, in the essay [“A Dog Named Humphrey”]. Sometimes I plop myself into these situations… but I never do it with the intention of getting an essay out of it. It’s just how I live my life.

Sure. You’re a writer who just happens to be in strange situations on a regular basis.

Maybe it’s what comes from diversifying your friends and your life and having a natural curiosity and things you’re interested in. The same thing that probably makes it so that I’m likely to end up in all these strange situations is probably the same thing that makes birthday parties a real nightmare for me. I think other people have this too—I don’t think I’m alone. I’m getting slightly better as I get older about having faith in people to be social and be fine and leave if they’re not having a good time, and that it’s fine and not a reflection on me, but I always get a little nervous that all these wildly different friend groups won’t get along with each other. But it’s great for writing.