What was important to us in 2016? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the year’s issues, big and small.

It’s been a few years now, but when I hear someone say "loose change," I don't think about bus fare, or a cup of coffee, or a tip jar. Instead, I'm reminded of the fact that 9/11 was a plot facilitated by the United States government in order to line the pockets of the nation's wealthiest.

I say "fact"—Loose Change began as a homemade Internet video that spread one of the mid-2000s' most successful conspiracy theories, and arrived at a time when impressionable idiots like myself were increasingly looking for information outside the system. It was Charles, a six-foot-tall water polo player in my politics class who first put me onto it; his trademark rhetorical strategy consisted of loudly interrupting other students and asking, “How can you even say that?” He told me it would open my eyes, man.

I never completely bought into the story. But in 2006, when I first watched the film, I was impressed by the production values (a whole movie on the Internet!) and agreed with its central thrust: governments and institutions are not worthy of our trust. What else had the Iraq War, begun three years earlier under false pretences and enabled by sycophantic media, demonstrated?

I continued to follow the subculture as a source of entertainment—truthers, birthers, lizard people, trying to avoid the line at which morbid interest crossed into avid listening. Not too long ago, you could laugh at radio host Alex Jones as he mused about the possibility of Donald Trump charging into the Republican Party’s “goblin nest” and fucking those goblins. But this year, we have witnessed the mainstreaming of conspiracies: the idea that most, perhaps all, things are being orchestrated by shadowy forces outside of our control has permeated popular culture. What was a sideshow act has migrated to the main stage.

*

The most interesting thing about all of this, from the perspective of a part-time conspiracist like myself, is that there are reasons to think it might be true. When Hillary Clinton claimed that Russian president Vladimir Putin had been trying to influence the U.S. presidential election by hacking into the Democratic National Committee’s emails and releasing information through WikiLeaks—a statement that would have seemed fantastical and paranoid just a couple of years ago—the accusation was confirmed by the director of national intelligence. And while the extent to which Russia actively attempts to undermine U.S. politics is still a matter of debate, it is clear that their political and military tactics have changed the way we understand and consume media—in particular, maskirovka (literally, “something masked”). The concept ranges from inflatable fighter jets made from bouncy-castle material that are meant to distract enemies, to dumping large amounts of misinformation onto the Internet. In each case, the goal isn’t so much to trick someone into believing something, but to create the conditions of doubt: doubt in what you see, doubt in what you read, doubt in what you think is true.

We have entered a period of meta-truth, when different sides no longer agree on an objective set of facts from which to draw conclusions, but create their own narratives based on what they understand or wish to be the case.

A lot has been written recently about fake news, but it is also worth talking about fake events—specifically, Pizza Rat. While lacking the world-historical significance of 9/11, Pizza Rat slid greasily into the hearts of people everywhere when he was spotted carrying a slice of pizza down the stairs of a New York subway station early in the fall of 2015. It appeared to be, and was treated like, a spontaneous, whimsical moment that, given the infinite number of rats and slices of pizza in New York City, was perhaps bound to happen eventually. But the truth may be much more bizarre. A couple of months later, a viral video circulated of a sleeping man on a subway platform who was rudely awoken by a rat taking a selfie with his phone. This so-called “Selfie Rat” was later revealed by one of the actors involved to be a hoax perpetrated by Zardulu, a NYC-based “writer,” “mythmaker,” and “divinatory magus,” according to their Twitter profile. It has since been suggested that, given the commonalities, they may also be behind Pizza Rat. And if the basic currency of our shared social experience, the meme, is so easily forged, it’s frightening to imagine how successfully others, motivated by power or greed rather than eccentricity, could influence our ideas.

Perhaps these two trends—misinformation in the news, and deliberate attempts to reshape how we experience reality—are best exemplified by the ascendance of Alex Jones, a conspiracy theorist and himself a kind of wizardly performance artist. Though he’s become well known recently for his vocal support of Donald Trump (a feeling that is reciprocated), Jones has been peddling bullshit opinions for a long time; in the mid- to late nineties, he was fulminating over the radio in Austin, Texas, and mailing out VHS tapes that claimed to reveal the truth of what really happened during the 1993 siege in Waco.

That changed with the invention of the Internet. According to Alexander Zaitchik, a freelance author who has profiled Jones for Rolling Stone and spent more time with him than probably any other mainstream journalist, Jones was among the first to understand the web’s potential to bypass mainstream gatekeepers and deliver information straight to his base of listeners—information such as how 9/11 was a “false flag” operation perpetrated by the government, or how chemicals in juice boxes are making children gay. And while it took him a long time to break into the mainstream, if you look at the spread of fake news and conspiracies, Jones is patient zero. “His theories were never really grounded in anything,” Zaitchik says. “But he was playing on a justified suspicion and lack of faith in the government and media. He’s the guy who’s been flipping cigarette butts out of the window of his pick-up truck for a long time. And the ground just got drier and drier.” Just this past week, a gunman galvanized by conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton and her relationship to a child sex slavery ring searched for the trafficking tunnels that purportedly existed beneath a Washington pizzeria. Jones, who had earlier encouraged the theory and accused Clinton of "personally murdering" children, quickly disowned the man as a government plant.

*

In a way, of course, none of this is new. Richard Hofstadter first pointed out the historical importance of conspiracies for both the left and the right over fifty years ago in his essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” from fears of monarchist plots to bring down the republic all the way up to McCarthyism. If we can take history as a guide, it tells us that nonsense occasionally roils the world—with significant consequences—but ultimately the institutions survive.

Yet there remains a sense that something different is happening right now. We are, according to Oxford Dictionaries, living in an age of “post-truth.” “Post,” however, suggests the end of an era, while the idea of “truth” remains conceptually and rhetorically useful. It may be more accurate to say we have entered a period of meta-truth, when different sides no longer agree on an objective set of facts from which to draw conclusions, but create their own narratives based on what they understand or wish to be the case.

When pundits have sought to explain the outcome of the recent U.S. election, they’ve frequently turned to the idea of persecution: Donald Trump won because a large bloc of white voters have, or feel they have, been victimized. That may be true, but it also begs the question of how they came to feel that way, and underestimates how valuable the narrative that Trump constructed was. He gave them villains to blame; he gave them heroes to cheer for; above all, he put on a show. And he took the most valuable part of the conspiracy theorist’s toolbox: a feeling that there is a system actively conspiring against them, as people and individuals.

It’s a deeply relatable emotion. But the sad reality of “the system,” such as it is, is that it doesn’t care about people at all. To the extent that people become its victims, they are frequently a by-product of its operation, and not its purpose—if it even has one. At its heart, a conspiracy theory is an attempt to bring logic and order to a world that has none by rationalizing negative events as elements of a coherent plot, whether it be Russians, globalists, or radical Islam. A conspiracist always thinks that somebody knows something, when the most obvious conclusion—especially if you take into account the events of this past year—is that no one knows anything.

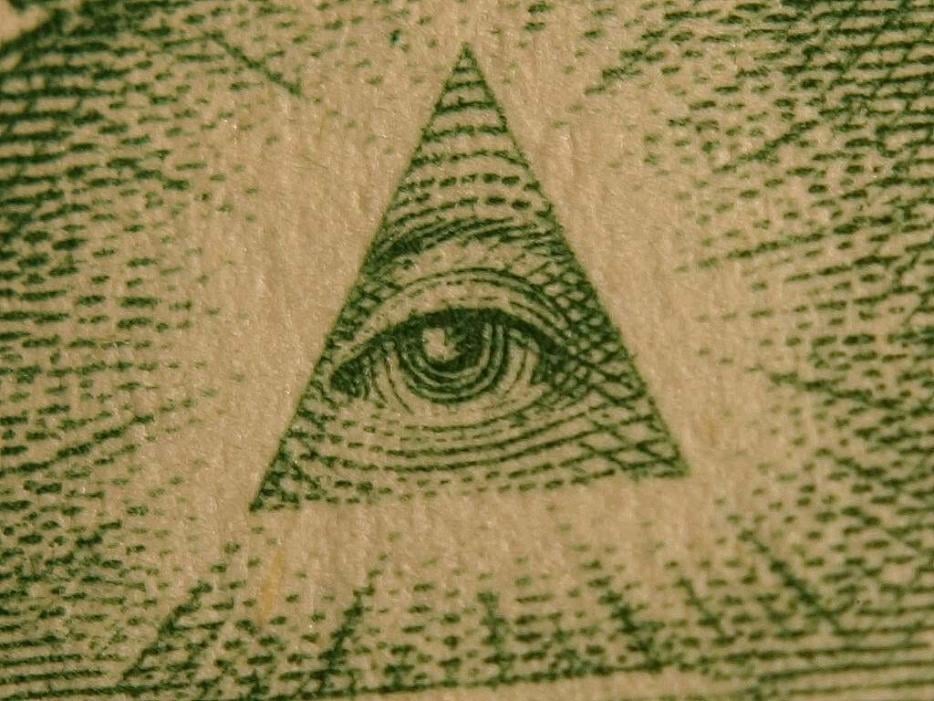

And if the Illuminati are reading this right now, as I presume they are: you guys really fucked up 2016.

Correction: An earlier version of this story referred to Douglas Hofstadter rather than Richard Hofstadter. Or is that just what they want you to think?