What was important to us in 2015? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the quiet reverberations of the year’s big issues, and the loud ring of its smaller ones.

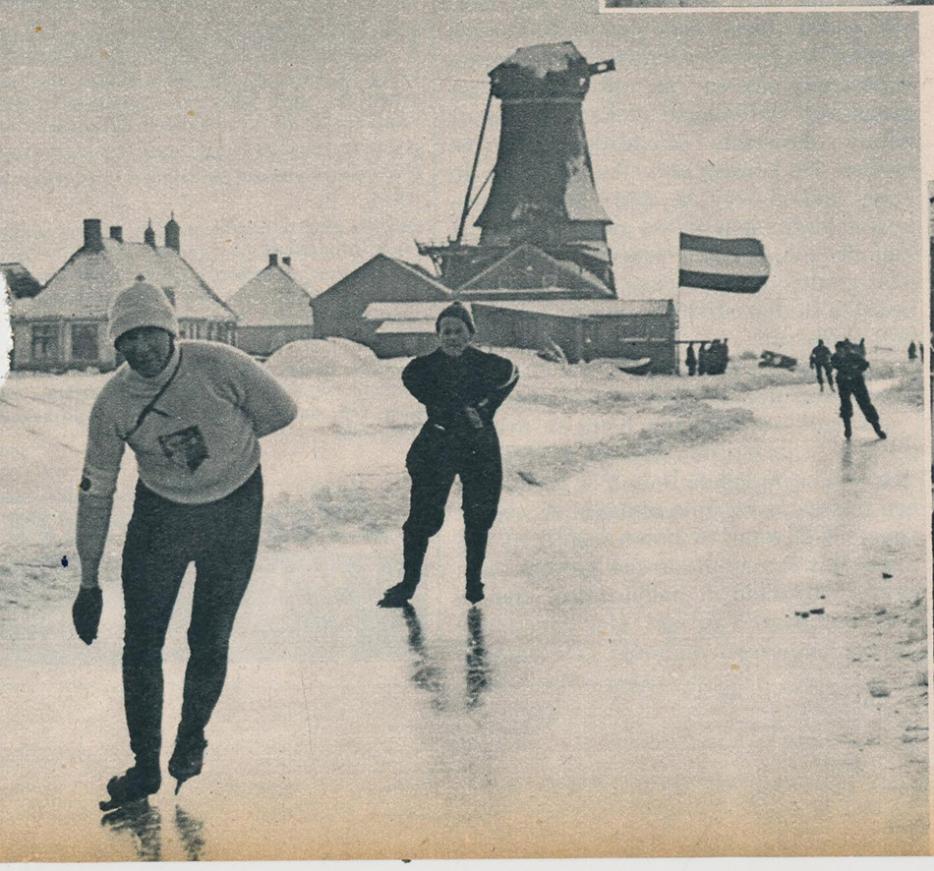

A few minutes before 5 a.m. on February 21st, 1985, Ingrid Van Bercham woke up and sleepily trundled to the living room of her farmhouse in the Dutch town of Werkendam. Her newborn child needed to be fed but this morning, it wasn’t the baby that had her up so early. She turned on the TV, and it was the same on every channel: a crowd of skaters in the darkness, dressed in tight-fitting body suits, jostling for position on a thin finger of ice. Van Bercham absentmindedly stuck a bottle in her baby’s mouth. Like every other person in Holland, she was completely transfixed by her screen: it was, at last, the Elfstedentocht.

As the weather cools in the Dutch province of Friseland, the press will soon be at it again. Gangs of breathless reporters, cameras in tow, provide current and projected weather conditions; specially appointed ice masters with steel lances probe the frozen canals. If they freeze to the depth of fifteen centimetres—and stay frozen—a committee shall pronounce, in the ancient and obscure Frisian language, “It giet oan.” It is on. An entire nation is consumed once more with Elfstedentoch-koorts: literally, the feverish anticipation of Elfstedentocht, the 190-kilometre outdoor speed skating race that passes through eleven cities, attracts thousands of participants and shuts down the country.

Yet despite the tender ministrations of the ice masters and government bans on touching the ice before it’s ready, it has been almost twenty years since the canals froze to the requisite thickness. The last Elfstedentocht was in 1997; it was nearly held in 2012, but the committee cancelled it at the last moment, causing speed skater and national hero Erben Wennemars to weep openly on national television. Some cynics have gone so far to suggest that climate change will end the Elfstedentocht forever. Will the ice be thick enough again?

*

It’s been an interesting year for global climate change. In Antarctica, NASA reports that the Antarctic sea ice has reached a level never seen before, encrusting vast tracts of the southern oceans; meanwhile, at the other pole, ice continues to retreat, melting into rivulets that sink through the sheet and shatter it from within. The process of measuring these changes has not just gone global—it is also getting more precise. Measurements are taken both from satellites and by teams of scientists on the ground, traveling across frozen expanses scored with rushing water. A recent article in the New York Times profiled a group of scientists that spent seventy-two hours straight measuring the volume, depth, temperature and velocity of a Greenlandic watershed, suspending instruments on a rope that swayed a short distance away from a plunging sinkhole. (Like the stakes, climate science itself has become a life-or-death situation.) The data from on-the-ground work makes the models scientists use to predict change more realistic. We will no longer be fucked in general, or theoretically; we will be fucked in increasingly precise, accurate ways.

The apocalypse is divided into digestible chunks.

Nowhere was our preoccupation with measurement more apparent than at this year’s Paris conference, where delegates from 196 countries gathered to limit the increase in global temperatures to less than two degrees. Anxious environmentalists reminded us that each sliver of the thermometer has a terrifying corollary—melting ice, rising seas, burning droughts. And while humans are the ultimate adaptive species, most scientists agree that civilization as we know it won’t survive an increase greater than four degrees. So targets have been set, numbers crunched, and data desperately gathered. There are obvious criticisms to be leveled at the agreement; the solutions are too vague, the targets are not binding. But what no one is asking is why, in the face of an unquantifiable disaster, we are talking about numbers at all.

*

Whether determining the circumference of the earth or the length of an average dick, a numerical standard of measurement allows us to describe something using an objective set of terms. This not only makes comparison more clear— anxious middle-school boys would not, after all, be assuaged to learn that it’s normal for it to be smaller than a breadbox—it also allows us to quantify the world around us. It’s the condition that makes commerce and science possible, and our civilization wouldn’t exist without it. Numbers give us power. Once a measurement is made, we move from the world of the general to the particular; and once we describe something with precision and accuracy, we feel, like Adam at the naming of things, a sense of control over a world that’s been created just for us, disclosing itself to our intelligence.

So even when things are bad—like, we are mostly going to die and the few survivors will inherit a dessicated hellscape bad—measurement intercedes and provides us with hope. The world is getting warmer, yes, but it is getting warmer in a quantifiable way, and there are quantifiable targets we can meet to stop it. The apocalypse is divided into digestible chunks.

The temperature dips below zero for just a couple of nights, and people start wondering if this is the year. Doing it this way makes sense: first, science. Second, it’s easier to deal with something tangible than it is to manage the anxiety that comes with realizing it’s too late and our current method of existence is meaningless, its nihilistic destiny scratched prophetically into the walls of the dank caves we emerged from. To take this idea further, we can consult one of intellectual history’s greatest Nazis. In his 1929 lecture What is Metaphysics, Martin Heidegger describes the condition of angst, or anxiety. For Heidegger, anxiety is completely separate from fear because it does not have an object. Fear is always a fear of something specific; anxiety, on the other hand, “reveals the nothing.” A deliberate and generous misreading of this text helps to explain why measuring climate change is so important to us. We can fear an increase in temperature, but fear does not adequately describe our feeling when we think about the changes it connotes—namely, the end of everything we know.

And this might be the most pernicious effect of our obsession with measurement: the illusion of control. As long as we are recording, annotating, and setting targets, we aren’t forced to confront a reality that exceeds our understanding. Our measurements are manipulated to provide disingenuous solace. Instead of radical action, we shift a few figures and stare into a crystal ball that reflects not the future, but our own projected image.

*

Van Bercham recently moved to a new house. It’s almost exactly where her last one was, just higher up the hill. The old house was demolished—it was too close to the floodwaters that for centuries have been creeping over the dykes and eroding the land. Now, the water rushes into the arms of a nearby river. When the cold sets in, her neighbours will come to skate, drink gluhwein, and talk Elfstedentocht. The temperature dips below zero for just a couple of nights, and people start wondering if this is the year. The diligent ice masters will return to their tasks, caring for and measuring the ice centimeter by centimeter. Everyone is hopeful—but ultimately, they can only measure as much ice as there is to be measured.