“I don’t know from community,” said Vivian Gornick when I called her on an early afternoon in late January. “I know from neighbourhood.” As a child growing up in the Bronx, Gornick kept watch over her people—family, friends, lovers, comrades, enemies—those that lived under the same roof or shared the same walls, passing through the same blocks or intersecting at the same corners. Today, Gornick still lives in Manhattan, and has never stopped watching the scenes of the city play out in front of her eyes. “I feel like a tough old New Yorker,” she explained when we talked about the way the city’s population has responded to the pandemic. “And I must say this: I’ve been immensely proud of our ability to comply quickly and early, and in an odd way, I think it has to do with New Yorkers being attached to New York. People are kinder on the street; I see that all the time, I experience it, I practice it, I see how quickly people rush to offer some sort of help when it is still needed.”

What turns proximity into solidarity? In the course of her career as an acclaimed critic, journalist, and memoirist, Gornick has often oriented her attention towards the collective: the way that groups of people experience a time or a cause greater than their own individual self. In the last fifty years she has published thirteen books and countless articles, many of which are classics of their respective genres. The 1969 article for The Village Voice, “The Next Great Moment in History Is Theirs,” for example, is a landmark account of a precise era in second-wave feminism as much as it is of her own newfound commitment to that cause. The recently re-released The Romance of American Communism, originally published in 1977, was a kind of oral history that stitched together first-hand recollections of people reflecting on the varying levels of attachment and disillusionment they experienced in years spent organizing with the Communist party. Her memoir Fierce Attachments, published ten years later, was another complex illumination on the nature of love and heartbreak between mothers, daughters, and everyone who comes in between.

In the last year alone, four books by Gornick have been released or reissued: alongside Romance, there are new editions of Approaching Eye Level, a collection of essays first published in 1996, and The End of the Novel of Love from 1997, critiques and observations about the changing role of romance in contemporary literature. Unfinished Business, in 2020, was a new work reflecting on the books Gornick has reread most in her life. “The timing of their publication could be chalked up to the return of American socialism, or to the tendency to rediscover women artists in old age,” wrote Dayna Tortorici in a career-spanning retrospective essay for The New York Review of Books. “But the lasting value of her work lies in her commitment to the question of what it means to feel ‘expressive’: to experience the feeling that tells a person ‘not approximately, but precisely’ who they are.”

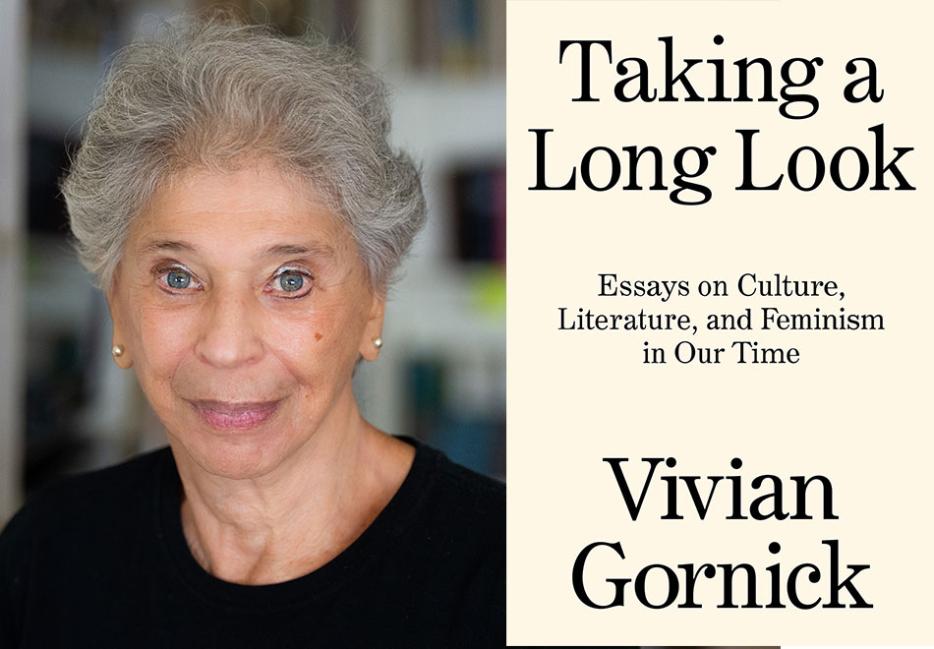

This month, Verso Books publishes Taking A Long Look: Essays on Culture, Literature, and Feminism in Our Time, previously published essays from the past forty years that encompass her distinctive signatures: there are the authors who do or don’t deserve their due, vivid accounts of unexpected conversations, feminist groups at a crossroads, and the ever-expanding definition of the ineffable affects of what can reasonably be called a sensibility. Always, always there is that feeling of the neighbourly quality that Gornick knows best, of being present to offer and receive as needed. We talked for exactly the hour we had agreed upon—at fifty-nine minutes, Gornick warmly but abruptly wrapped up our call—and in that time our conversation moved between the works included in Taking A Long Look, how Gornick is staying safe in the pandemic, rereading her own rhetoric, and the feeling of living through histories. In having another occasion to consider Gornick, there are more opportunities to celebrate what makes her writing so distinctly her own—she is the rare writer who always wants to find, in a chorus, a voice.

Haley Mlotek: You recently wrote about the changes the pandemic has forced on us. I wanted to ask if you have personally developed any new habits over the last year.

Vivian Gornick: There’s this contradiction. On the one hand, I can say I live very much as I always have. I live alone, I work alone; of course, I’m used to being alone more than a lot of other people. On the other hand, it feels like it’s going on in some unreal circumstance. I still feel, like everybody else, that I’m living in a fog. I used to go out every single night to a play, movie, dinner, and I forget constantly that I can’t—I’m one of those people who whenever somebody says, like you, “Want to have a conversation?” I always say, “Oh, sure, I’ll meet you in the park.” I forget completely that it has to be the telephone, or this Zooming business, which I hate.

In other words, it has created a lot of tension. I’m awed by the realization that I’m living through a world historic crisis. I’m very aware that the world has not been like this in one hundred years.

And along those lines, I do have to say that I’m one of those writers who has always resisted the journalistic jump to proclaiming “the world will never be the same,” blah blah blah. When people ask, “What do you think comes next? What do you think the world will be like when this is over?” I always say, “How do I know? What do I know?” I’m aware of it, but I wouldn’t comment on it.

Your work frequently references taking a reader behind your eyes and showing them what you want them to see—what are you looking at lately?

I’ve been preoccupied with an essay I’ve been writing for a long, long time, on one of those lost writers. I discovered him when his work was republished and was immensely hooked emotionally on the tone, the feel, all the unspoken spokenness in his writing, and I wanted very much to write a piece that would make a reader feel what I felt. That’s always the aim. If I was a journalist, or a correspondent of some sort, I would want urgently for you to have the facts as I have them. But as I am, the hybrid writer, I want to tell a story. I want the reader to feel, rather than be instructed or given information. I guess that’s what my writing life has been devoted to. I don’t think I have a brilliant mind, but I have strong feelings and those strong feelings are my pride. They are what urge me to make my mind elucidate those feelings.

I’m curious to know, when you talk about offering a feeling to a reader, if there are any formal qualities to a piece of writing that can communicate emotion—are there any particular properties of language that you find yourself relying on to transfer a feeling?

That is such a hard question to answer.

Sorry!

And you know, especially for me, since I am not a writer who pays a great deal of attention to exactly what you’ve just described. “The properties of language” is a phrase that has never been in my vocabulary. I’m sure I employ some, but I started as a polemicist at The Village Voice, covering radical feminism, and that taught me the meaning of a point of view. I didn’t hesitate to use rhetoric. I was involved in making a political and cultural point, and I was conscious of that. I wanted the reader to feel what I was feeling, but it wasn’t writerly; it was political and cultural.

When I wrote Fierce Attachments, I became another sort of writer, a memoirist. The individuation of emotional intelligence was there rather than cultural or political intelligence, but I retained the importance of that point of view, which had to control all the material. The language had to get more and more refined if it was to really do an adequate job of connecting the reader as I wanted to.

In this collection, for instance, the last section reproduces some of those feminist essays from those days. I didn’t want them in, because I can’t stand the rhetoric in most of them, but my editor insisted because they’re part of my history. And that’s certainly true. But when I read it, I see the care with which I developed over the years in culling those sentences completely free of rhetoric. I was able more and more to catch myself when I was falling into locutions like “beyond a doubt” or “there is no question that,” and similar stuff that I did more than my share of. I would write these long, fancy sentences that had too many words in them. Now I’m more devoted to the simple sentence, the clear and lucid one.

You mentioned something that I did want to ask about—how you decided which essays to include in this collection—and so I guess there’s one answer, that your editor recommended you include what seemed most relevant to your history.

If I could bear the rhetoric, it went in. Most of the pieces I still stand by. There’s very little in which I think I was off the mark. The essays that felt like a bridge between now and then are in it, but mostly I think if you look through all the pieces that were written over those years, the line of thinking does develop. I’m looking with more nuance at the situation, which has, of course, remained the same all of those years. I like the pieces in that sense. They make some important observations about the situation as it was then. You know, for us, it was all reinventing the wheel. It was all an astonishing sudden discovery. And the richness of whatever I have written, they’re all much more reminiscent of the time than anything else: of the atmosphere with which people like me were saying, “Can you believe this?” Which now feels so nostalgia-ridden.

I often do wish I was back there, because it was so full of hope. When the #MeToo movement hit three years ago, I was so shocked and pained to see, in a certain sense, how little had changed. I’ve been telling this to young people a lot lately. I know as a young woman I thought, forty years from now, my god, it’ll be another world. And in some sense, it is. We’ve accomplished a tremendous amount. On the other hand, it makes you realize it isn’t over until it’s over. To some degree, that’s made me a little bitter. Bitterness isn’t my style, but I do feel it when I regret that as hard as things were forty years ago, you could believe in progress. You could believe a new world was coming.

Nevertheless, I’m really proud of all the young women who do so much. It really thrills me that whenever anything happens that’s violently sexist, in ten minutes, the whole world of the internet lights up. Thousands of wonderfully intelligent young women throwing in their two cents. I feel mother to it all, grandmother, but I do like that a lot.

In the same way, when The Romance of American Communism was reissued last year, you mentioned being a little surprised by the response and feeling conflicted about the writing. I was wondering how you felt about today’s romance for that particular era of organizing.

Well, you know, romance is more than a double-edged sword. Romance is something that I fall to, like many. At the same time, second-wave feminism was very big on resisting romance. I wanted to see things as they were, and I’ve written a lot about that—about resisting sentimentality. When I chose the title, I meant it in a lot of different ways, and now young people respond in ways that are shocking to me. The romance of Communism speaks to some of the downsides of what it was—it speaks for the bittersweet longing to be part of something larger than yourself. The book is meant to be a record of people both succumbing to and fighting the authoritarianism of a piece of moral philosophy that they couldn’t walk away from. I’m very sympathetic to it. It broke my heart. At the same time, I think I romanticized it myself, and so to watch other people romanticize it even further away from the realities has just been a shock to me. That’s essentially it.

When I was rereading a lot of your work, I noticed how consistently you write about the role the collective has played in your life, and how important it is to resist or critique the idea of “the brilliant exceptions,” those singular stars of a movement. But I was thinking, too, how hard that is for both writing and research—literature wants a protagonist, and history wants a leader. As a writer, how do you deal with that sort of central tension between the way things are and the elements that make a good story?

It’s very hard. Well, actually, I shouldn’t say it’s hard. It depends on what your agenda is. If I set out to tell a story about the psychological and emotional complications among people, that’s one thing. If I am setting out to call attention to a moral or social injustice that I feel strongly about, that’s another thing. When you apply that word to writers—agenda—you say that a journalist has one agenda, and a novelist has another. You take the same piece of material, you take the same set of circumstances, you take the same protagonist, and you come up with something completely different in each. There are different uses at different times.

Even in the period of radical feminism that I associate myself with, I hardly ever could go to a meeting. I couldn’t stand the meetings. I did it out of a sense of obligation to the movement, but there was a time when the collective stirred me deeply. As I got older, it became less and less compelling to put aside the injustices that, in seeking justice for myself, I inevitably committed against others. Look again at the #MeToo movement. It has pained me horribly to see due process at work. I won’t go overboard to see men whose crimes were not of a criminal [nature] being punished as if they were.

It’s very hard to think two things at once, but I more or less do. I’m very glad that #MeToo developed. I could never disavow it. Never. On the other hand, if I’m in the jury box, it feels like every single case has to be fought on its own terms. There can be no looking at things and saying that it’s just because he’s a man, even though I often feel that way. We’ll never get justice with that approach. Whereas 40 years ago, I think I wouldn’t have thought twice about any of it; I would have been “off with his head,” like everyone else. It’s a hard time to live all over again. I’ve had to think more about these things than I had in a long time, and I’ve enjoyed that. But I have no great wisdom on the subject.

It seems that there’s a similar tension between the collective and the individual when you talk about stories of an injustice done by one person. How do you respond to one instance, knowing that one person is an actor in, or a representative of, an entire system, but not necessarily the inventor of it?

Precisely. And I think that’s the better part of valour to square that. To pay more attention to individual justice and collective punishment.

But then, what changed for you? I know a lot of time passed, and with that time any change is natural, but do you see any sort of defined reasons for how your thinking is different now?

When I was writing for the Voice, it wasn’t that I was looking to punish people who others might think were innocent or anything like that. It was just the way I saw things. I went out into the street; I saw sexism everywhere. It was my absorption. It was the colour of the world, the sound of the air. I can’t explain it any more than that. It was the way others have described a sudden conversion to religion.

At the same time, I was in the middle of a divorce, and I wasn’t getting divorced because I suddenly saw my husband as a sexist pig. He wasn’t at all. But I had no compassion whatsoever. There were definitely male-female things that were driving us apart without me being overtly political about it. I could never see his side, never. No matter what happened, I just could not see things the way he saw them, and I don’t think that’s true anymore. I don’t know if that’s good or bad. He would often say to me: “It’s taken me my whole life to learn the rules, and now you’re pulling them out from under my feet.”

So, there’s too many things to consider here. On the one hand I defend them as individuals for whom the punishment does not fit the crime. On the other hand, I wouldn’t let them off the hook for a second. We have a lot on our plate. We all have to become philosophers.

And to go back to your metaphor about being in the jury box, part of what makes this so hard is to watch how quickly people would prefer to think of themselves as prosecutors rather than philosophers.

Right. But you have made it a much more interesting time to be living in.

Relatedly, there was a phrase in one of your earlier essays that I paused at—you mention the struggle of being in a “transitional generation,” and I instinctively related to that, but it made me think: is any generation not transitional? Does anybody arrive in the moment they’re meant to be in?

Well, I don’t think my mother lived in a transitional generation. There are a lot of decades that are sort of somnolent. Politics and society are in a dead lull. Look at Victorian times, for instance; there was no transitional generation for like 50, 60 years. The whole second half of the 20th century is constant turbulence. Just think about the things that have happened since the 1940s and ’50s. My mother used to say to me, with great bitterness, that this time was shocking to her. She said, “We lived decent lives, sweetie.” She would say that the unhappiness was so alive. And I said, “Ma, that’s the only way things change, when the unhappiness is alive.” And that was the truth about her life. She lived this ordinary, repressed life in which people never got divorced, never thought about the actual marriages they were living through. Now it’s change, every ten years.

Living through history is bumpy.

Yeah. You’re living in history. We’re all living in history. They were not. Me and my brother and my nieces, our lives have been utterly different. Utterly.

Okay, my dear, I think that’s it.