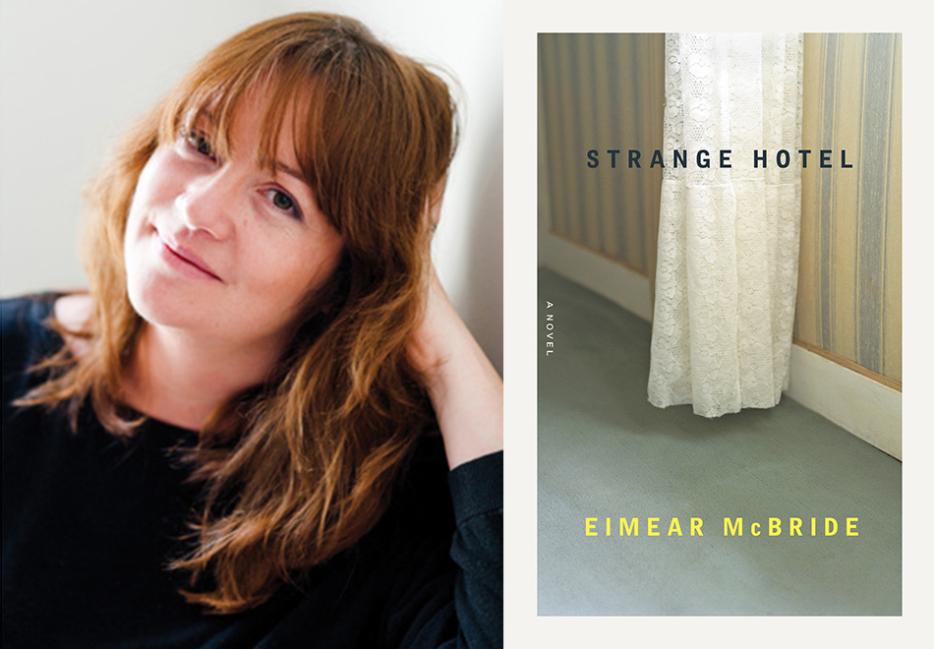

Eimear McBride’s debut novel, A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, and its follow up, The Lesser Bohemians, were dazzling reminders to the mainstream anglophone literary scene that fiction could still be a language event. Innovative and uncompromising Bildungsromane tracing the formative, furtive, often brutal experiences of their young female protagonists, both books were distinguished above all by the shattering linguistic inventiveness of their first-person voices. McBride’s prose was protean, agitated, and exquisitely receptive, intent on barrelling past mere communication toward a state of total visceral embodiment. Here were sentences and sentence-fragments that seemed wired into the very nerve-ends of their protagonists, capable of registering their every minute physical and emotional perturbation.

Strange Hotel (McClelland & Stewart), by contrast, is written in the third person rather than the first, in sentences that, while still rich with McBridean obliquity and a forensic attentiveness to the subtle, incessant fluctuations of the senses and the mind, nonetheless more closely approach conventional syntactic units. But even a more traditionally shaped McBride sentence is rife with inimitable turns of phrase and is still intent on interrogating to the limit what can be registered and expressed in language. If the self is sui generis, requiring, as in McBride’s first two novels, the total breaking apart of language in order to remake language in the self’s own singular image, what does that mean for a self that remains within the boundaries of what might be called conventional expression? Is that self seeking expression, an image of itself, at all? Does it want to be seen? And if not, why not?

That self, the protagonist of Strange Hotel, is a woman with a name we do not know and about whom, in many respects, we get to know very little. What we do know is that she is approaching middle age, and that whatever her occupation is—several passages in the book emphasize it has something to do with language—it requires her to travel extensively. A list of cities transitions the reader from one scene to the next. Each scene takes place in another hotel room in another city. The present tense action consists of little more than the woman ordering wine from room service, idly considering if the drop from the balcony would be sufficient to kill her, or watching the sleeping back of a one night stand; what preoccupies her is her past, and the distance, geographically as well as temporally, she might achieve from it in the purposeful anonymity of these hotel rooms. There is something she wants to forget, or more precisely, not remember: "… allowing memory, or any of its variables, admittance is invariably a mistake. Nonetheless, and even knowing that much, time makes a ladder of her anyway."

This interview was conducted via phone call in early June.

*

Colin Barrett: In the opening scene of Strange Hotel, a woman walks into a hotel room in Avignon and suddenly realizes she has been here before. This mundane cosmic coincidence opens a rich seam of memory in her. As she tries to recall the particulars of her previous stay, we come to realize that she is trying to keep other memories at bay, and that she is trying to achieve that by being hyper-focused on the present. As the book proceeds, we see her traverse an endless chain of hotel rooms. Did this premise come first, or did it emerge out of your sense of this particular character, who is capable of elaborating at length on certain things, but being scrupulously reticent about others? Can you even make a distinction between the premise and the characters on one hand, and the writing style on the other?

Eimear McBride: I find it quite hard to separate them out. Writing is a complete process of discovery beginning to end. I don’t arrive with the plot ready, or the characters, or the style in which I want to write. It all emerges in a sort of rush and mess together, and it’s my job to pick my way through it and make sense of it.

Strange Hotel originally started as a short story, which is unusual for me because I’m really not a short story writer, and clearly, I’m still not a short story writer [laughs]. At the beginning I felt there was a gain in going against what I’d written in the past, and so rather than use fractured perspective, narrative, and syntax to bring the character closer to the reader, I wanted to use language in a really different way. I wanted to write about someone using language as a means of creating distance, not only with the reader but within themselves. It was fun being contrary about that because there had been some criticism of how opaque my other books were, how difficult they were. So it was fun to use really formal, correct, linear sentences, where everything was correctly punctuated, in order to show how even straightforward language doesn’t actually aid communication.

I’d written two books about much younger women and I felt the language they were written in really conveyed urgency, that experience of life when you’re young, the almost overwhelming nature of it. In this book the protagonist is someone who is not very inclined to be overwhelmed, who wants to keep her distance, who doesn’t want to be very close to her memories or her pain or to the people around her. Somebody who is going to be much older. And so I realised early on I would be writing about a middle aged woman instead of a young woman.

Even though the book is written in the third person, and the reader sees the woman from “outside” herself, there is still, by conventional standards, a paucity of expositional detail about who she is and what her backstory is, to use an industry term. We don’t know her name, why she is in any of the places she is in, etc. Holding back that information while writing in the third person presents its own challenges. What was it that compelled you to make the decision to write this way?

I thought, “I’ll have a go.” Of course it’s not proper third person at all, it’s close third. The reader is allowed into her thought process as it’s going along, which is why there is no explanation, why she is thinking the things she’s thinking, and you just have to pick up what the details are, what the backstory is, in the way that you do when you think about your life, when you think about something that happened. You don’t think about the things that led up to it, that’s not how the thought process works. In a way we take lots for granted, our understanding of ourselves. So part of the challenge was to make sure there was enough there to suggest to the reader the bigger picture, but at the same time not succumb to that convention of the character looking in the mirror, describing how they look, etc.

That makes sense. I mean, when we are experiencing our memories, thinking about our past, we don’t do so in an ordered, detailed sequence, the way it tends to be delivered in stories. Another trait of the character, and the writing itself, is the heightened attention, the granular focus, she gives to even the completely mundane and generic fixtures in and around the various hotels she’s staying in, the way the light falls on a hallway wall through the slats on the windows, the difference in textures between the filters of British versus European cigarettes stubbed out in the sand on the beach…

She does not prioritize deep thoughts. She is not interested in cultivating great moments of revelation, or thinking about works of art or anything profound. What I was interested in is the diplomatic thing the eye does when it falls on anything, it gives the thing the attention it wants to give it, rather than the attention that thing might or might not deserve.

Character is the thing I’m most interested in, and how language serves that. In this case, there is a character who is not interested in feeling. At the moment I’m feeling exhausted by how much feeling everyone is having all the time, and how much shouting there is going on, on the internet, etc. Everyone is expressing everything all the time. It was a relief to write about a character who wasn’t interested in making sure everyone knew how she felt. She is someone who is really, really quite preoccupied with not being at the mercy of her emotions. So it was really about writing a book that was about thinking about feeling, rather than feeling itself.

The book does definitely have a plot, and she definitely does have a backstory, but her history is revealed in brief, allusive glimpses rather than in chunks of direct exposition. You said you think of character first; in relation to the reader did you agonize over that stuff, about how explicit you should be in fleshing out the character? Did you always know what the key points of her past were, or did it surprise you as you were writing it?

It did surprise me. It’s something I always thinks about in the second draft more than the first draft. You can’t just write what you’re writing, you have to be a writer. You are aware of wanting to be read, and while you don’t cater to what you think the reader’s expectations will be, at the same time you have to acknowledge that you are not really writing it to put it in the drawer. You have to give enough to the reader to allow them to make the picture for themselves. But it is very hard to assess that, the writer’s instinct has to try and gauge that, and you can’t know whether you’ve gauged it correctly or not until it’s published and people read it. They understand or they don’t understand. But I think it’s an impossible thing to plan for.

I do think that readers are far more tolerant and patient than they are given credit for, and all the faff to get Girl published and all the publishers who thought no one would ever read a book like that, it was proved that that was not the case. There are plenty of readers willing to have a go. It’s not that they necessarily love it or want to read lots of books like that, but they enjoy being obliged to engage with writing in a different sort of way, not just the usual, “Here’s the story, here’s the characters, here’s what happened, the end.”

I think there are readers for whom process is enough. It’s not about the big finish. Readers are interested in character. It’s the endless fight isn’t it, the pushing, pushing, pushing, the prioritisation of plot above all else, but there are plenty of readers for whom that is not the be-all and end-all of the reading experience. It’s okay for some books not to have to engage readers in that way, although you’d think from the reaction of the critical press it was the most terrible thing you can do to a reader, expect them to pay attention to a book. That interests me. And I hope there’s enough weirdos out there like me, who are also interested in that!

I wanted to ask about the treatment of time. It’s a short book, it traverses huge expanses of time and space, taking place all over the world and over a number of years. Yet each scene takes place in a kind of cool, dead, parenthetical interval, where on the surface nothing much is happening. Things have happened to the character, but each time we see her she is stuck in the present, in nowhere, a kind of nowhere time.

When you’re younger, you don’t think about time, and when you’re older things become more urgent. Things feel like they have already slipped by, things have been missed, and I suppose in the midst of the travelling and the hotel rooms there is the idea that wherever you go and however freeing the anonymity is, there is, ultimately, no escape from the self—your self—that is continuing to move through time whether you want it to or not. She really would prefer time not be moving on, not because she doesn’t want to be older, not because she wants to be a young woman again, but because, as becomes clear, she feels that everything that is going to happen has happened. She is seeking a kind of stasis. What she can control is her interactions with other people and so she is seeking to stop the possibility of all that, of future intimacy and closeness. She wants to stop time within herself in a bid to hold herself close to the time that was once meaningful.

She’s stuck. She does not want to move on, but also is trying to barricade herself psychically against the encroachment of her own past. She seems to be pursuing the idea that she can will herself into anonymity, disintegrate her personality, allow it to take on new shapes, or no shape at all. But the more she tries to do exactly that, the more she seems to loop back to her foundational concerns, to the matrix of her personality…

I think she wishes she could do that. She is able to dissolve herself to a degree, but continuously returns to this very firm sense of herself. That sense of self doesn’t necessarily follow, or isn’t expressed, in all the usual markers of identity, like family, job, financial status, but it’s still there, this fundamental knowledge that she cannot escape, even though she wishes to. I don’t think of the self as being amorphous. While there are all these markers of identity that we display as emblems of self, beyond all that there is a harder, darker, colder bit, right at our centre. A bit that maybe we find harder to live with, but it is the bit that counts, that never changes, that never becomes anything else and which is quite hard to deal with.

Lastly, the book got me thinking about hotels. In the book they function as as these sort temporal waystations, outside of time almost, where the protagonists can think about time, her own experiences in time. And above being either luxuries or expediencies, that’s what hotels are, these interstitial spaces that operate by their own logic of time, outside of ordinary time. Wherever you go a hotel operates on hotel time, and you really begin to feel it if you stay in one for more than a handful of nights. You can go get a drink, or have a swim or whatever if there’s a pool, but it’s all preset, on a loop… it gets weird after a time.

A hotel is a place you go to wait. You are waiting for a thing to happen, or you are waiting to leave. Eventually, you realize that it’s just you in a space, and there’s nothing else. You don’t have to go cook the dinner, or help with homework, or walk the dog, there’s nothing to distract you. You are a body floating in space, in this anonymous space, just being yourself, and either engaging with that self or trying not to engage with yourself.

You don’t have to do anything, that’s the rationale behind a hotel, you don’t have to do anything. I don’t know how comfortable most people are with that...

Maybe you should have to make your own bed when you arrive!

It would be something to do.

Well, that would invest you in some way, into the experience of the room. You realize there’s a whole machinery working around you; of people that are invested in their jobs, in their relations with their co-workers, the welfare of the guests, but you—the guest—are not part of that. You are outside of all that. You are the reason everyone is there. But you yourself, you have no reason.