1. ¡Sandinistas!

There was a small ceremony on the steps of the municipal building on the western edge of Plaza Colon in the evening of my first day in Granada, Nicaragua’s quiet old colonial capital. I came upon it by accident as I strolled around the city’s grand central square with my wife and kids. Traditional music played over a loudspeaker as young women in pastel-coloured dresses with long lace-trimmed hems performed old-fashioned dance steps. A banner above read “80 AÑOS SANDINO.”

I’d arrived in Nicaragua, I realized, just before the 80th anniversary of Augusto Sandino’s assassination. Sandino was the martyred hero and namesake of Nicaragua’s socialist revolution. He’d led a doomed rebellion in the 1920s and 1930s against the U.S.-backed regime that gave birth to the Somoza dictatorship, which would rule the country until the Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional—the FSLN, better known as the Sandinistas—toppled it in 1980. Granada has always been a conservative town—conservative in the colonial era’s sense, loyal neither to the Sandinistas nor the contra guerilla army the American government would secretly arm to oppose them—and I supposed that was the explanation for such a modest ceremony. I’d spied an FSLN monument in the middle of the boulevard on the way into town, but I’d also seen graffiti referring to current Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, a Sandinista war hero, as a dictator.11The spraypainted slogan read “no mas dictadura orteguista” (“No more Ortega-style dictatorship”)

We watched the dancing for awhile and then strolled across the square, past the grand old cathedral with its exuberant yellow walls and cake-icing trim to Calle Calzado, the main tourist drag. In the middle of a block thick with outdoor cafés on either side, a group of young men had set up a boombox. To old-school hip-hop beats, they took turns performing headspins and acrobatic flips. We stopped to watch them for awhile too.

Contemporary takes on Sandino-era flamenco and Reagan-era breakdancing—you can’t script symmetry this tidy. On either side of the main square in the heart of colonial Nicaragua, two troops danced in celebration of the competing cultures that had vied for the country’s soul—and its seat of government—in the 1980s, thereby catapulting Nicaragua to the top of America’s foreign policy agenda and the vanguard of left-wing activism the world over.

Later, from the courtyard of our hotel, we could just barely see a smattering of fireworks. When it was over, I returned to my reading and marvelled at just how much I’d forgotten—how much we all had—about the whole sordid global web contained in the phrase “Iran-contra.”

I spent my final year of undergrad in the mid-1990s wholly immersed in the calamitous politics of Reagan-era Central America, lingering longest in the morass of the Iran-Contra scandal. My honours thesis dissected the strange way America’s mainstream media chose to turn a president’s straightforward and exceedingly well-documented breach of the Constitution into a contained and confusing minor scandal—a chapter so incidental that it has been all but erased from America’s collective memory as Reagan has ascended to conservative sainthood. I could go on22If anyone wants 10,000 words and/or a two-hour rant on Chomsky and Gramsci, the Sandinista victory and American conservative hegemony, corporate collusion and mass media bias—among other things—please do feel free to drop me a line., but this isn’t a story about what Iran-contra was then so much as what it’s become. Granada was just a prelude for me. I was bound for Costa Rica, to see what monuments remained to the grim legacy of Oliver North’s illegal war.

His paymasters included one Rafael Qunitero, a Cuban-American whose 2006 New York Times obituary confirmed Tolliver’s assumption—that Quintero was a long-serving CIA operative, a veteran of the Bay of Pigs fiasco who was drawing $4,000 a month from North’s payroll to oversee arms shipments to the contras.As I said, it’s amazing how much we’ve forgotten. On my Central American trip, I was reading a handful of books from the voluminous reportage of the war itself—Christopher Dickey’s With the Contras, Leslie Cockburn’s Out of Control, Gary Webb’s Dark Alliance—and the random detail on any given page seems like it should have been enough to incarcerate Ollie and impeach old Ronnie. Cockburn reports, for example, that in the first few months of 1986 the U.S. government’s Nicaraguan Humanitarian Aid Office handed nearly a quarter of a million dollars to the three directors of a Costa Rican shrimp export business called Frigorificos de Puntarenas; at least one of the directors was named in a contemporary FBI affidavit as a cocaine trafficker. In a separate incident in March 1986, a private pilot named Mickey Tolliver—who Cockburn describes as “the Nick Nolte of the drug pilot set”—flew a DC-6 loaded with 25,360 pounds of marijuana from a contra supply base operated by the CIA in Honduras to Homestead Air Base in Florida, where Tolliver was escorted off the runway in a waiting truck and paid $75,000 for his work. His paymasters included one Rafael Qunitero, a Cuban-American whose 2006 New York Times obituary confirmed Tolliver’s assumption—that Quintero was a long-serving CIA operative, a veteran of the Bay of Pigs fiasco who was drawing $4,000 a month from North’s payroll to oversee arms shipments to the contras.

Let’s set aside for a moment that Oliver North’s little enterprise involved violating a congressional order not to trade arms with Iran, then using the proceeds from that illegal operation to fund a project violating another congressional order banning the provision of arms and support to the contras, both of which acts breached the Constitution. Let’s simply marvel at the fact that Cockburn documented for CBS News in 1987 that planeloads full of drugs were travelling from Honduras to an American military base with enough frequency that the Nick Nolte of the drug pilot set breezed his way off-base at Homestead after delivering 12 tons of pot there.33Twelve. Tons. This was at the very peak of the Reagan administration’s just-say-no war-on-drugs hysteria. Tolliver, speaking on national television: “My best guess would be that it would have to be someone in the top four, three slots of the CIA as I know their organization. It has to be someone that high up, because who else can you get that’s going to pick up a phone and say, ‘Let this happen’?"

To be fair, North did face trial on 16 felony charges. He was convicted of three, sentenced to probation and community service. All charges were dismissed on appeal, however, and North was nearly elected to the U.S. Senate in Virginia in 1994. His syndicated radio show premiered in 1995, and he has since become a bestselling author and frequent commentator on Fox News. He appeared as himself in the 2012 videogame Call of Duty: Black Ops II. He is mostly remembered now, especially by the misty-eyed American right, as a brave Cold Warrior unfairly forced to take the fall for a patriotic effort to stop the commies in Central America. And Saint Reagan, of course, is an icon looming so colossal and beatific over contemporary American politics that even President Obama feels obliged to genuflect on occasion before his image.

2. Road to Nowhere

The main historic attraction at Santa Rosa National Park in the northwest corner of Costa Rica is La Casona, a 19th-century ranch house where the Costa Rican militia defeated the private army of William Walker in 1856. (Walker, a gentleman adventurer from Tennessee, had come to Central America to establish slave states to feed the plantations of the U.S. South. The American visitor with a big idea has all too often been more curse than blessing in Central American history.)

Just beyond the old ranch, the road turns to gravel and forks toward the ocean 12 kilometres away. A sign reads “WARNING!! ROAD IN BAD CONDITION / WE SUGGEST NOT TO DRIVE ON IT / WALKING RECOMMENDED / DRIVE AT YOUR OWN RISK.” The reason I chose to drive on, in a rented Kia 4X4 crossover with my wife and kids in tow, was because of Saint Reagan. Because myths like this grow and prosper in the absence of counter-narratives. Because there was a sort of monument at the far end of this road in bad condition, a trace memory of the real story of America in the 1980s.

Because myths like this grow and prosper in the absence of counter-narratives. Because there was a sort of monument at the far end of this road in bad condition, a trace memory of the real story of America in the 1980s.The road—easily the worst road I’ve ever traversed that wasn’t in the process of being washed out at that actual moment44My wife and I were once driven across the Ganges plain along secondary highways in a rattling old Ambassador cab the day the monsoon broke, otherwise the road to Playa Naranjo would be my personal Worst Road Ever in all categories.—wound through jungle and dry riverbed and over steep jagged ridges and green hills to a pristine beach called Playa Naranjo. Most visitors to this stretch of pale sand come by chartered boat from the resort communities down the coast—surfers bent on riding the intense waves of a legendary surf break at the north end of the beach called Ollie’s Point. It is the only named monument—and then only colloquially—to the string of air strips and supply camps Oliver North’s network once ran in northern Costa Rica. It is, in that sense, the contra war’s only identified historic site.

Ruts and jagged humps of volcanic rock turned the road to Ollie’s Point into a bewildering maze we didn’t so much drive as navigate by deliberate plotted turns, like a marble in one of those wooden tilting labyrinths. We had to stop in several spots to map out our next maneuvers, and eventually my wife took over the driving, as is our family custom in such hairy situations. It was mid-afternoon, ferociously hot, and we knew we would have to get in and back out of Playa Naranjo by sundown. There was no driving this road in darkness.

I was convinced at least twice that we’d reached an insurmountable obstacle, that Ollie’s Point would remain just a hypothesis on the washed-out horizon, but somehow we reached the coast. We parked, hiked the last hundred metres to the beach past a smattering of campsites (only one in use), and surveyed the scene.

Playa Naranjo is a gorgeous sweep of soft pale gold sand, shadeless and pounded by surf. We walked to the water’s edge, but a sign back at the treeline pointed to a crocodile lagoon 300 metres south, convincing us not to take a swim. The north rim of the beach was a series of jutting rocky volcanic fingers extending into the churning Pacific. I felt sort of journalistically obliged to try to reach them, but the distance was hard to measure in the blinding sun and looked far enough to more or less guarantee heat stroke. There was, as well, the possibility of crocodiles unflagged by National Park warning signs. There were little explosions of white foam off one of the dark promontories in the distance, and I decided that one must be Ollie’s Point. An actual location, even roughly speaking, to mark on the map against a deleted chapter in American history.

There wasn’t much else to do at Playa Naranjo. I’d come, after all, to witness a monument’s absence. The historic plaque, had there been one, might have read: Somewhere in this forest in the mid-1980s, a landing strip was cleared to receive aircraft loaded with weapons purchased illegally by the American government using money earned by illegally selling arms to Iran, thus to fuel a vicious civil war further north. The airstrip may or may not also have been used as a trans-shipment point for wholesale quantities of cocaine and other illicit substances, which may or may not have gone on to the United States on the very same airplanes. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan described the beneficiaries of this trade as “the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers.” By 1987, the whole grim affair was over.

The airstrip may or may not also have been used as a trans-shipment point for wholesale quantities of cocaine and other illicit substances, which may or may not have gone on to the United States on the very same airplanes.Anyway, it was too hot to linger, the crocodiles loomed to our immediate south, and WTF? looks had begun to creep across both my children’s faces. Thankfully a troop of capuchin monkeys swung through the canopy above as we reached the car, placating them for the bone-rattling ride back along the canyon ruts of the road.

The light grew twilight soft, golden like the sand of Playa Naranjo. I could only wonder what it was like to hunt this horizon for signs of a cargo plane laden with the next shipment. Only wonder, really, how a whole culture had emerged in the years after World War II, nurtured itself on the black ops Air America raids of Southeast Asia, merged with the pathologically anti-communist Cuban exile community in Miami, decided that the near-term political fate of a tiny under-developed Central American nation was worth more than the U.S. Constitution. And yet here it was all around me, the dense jungle where so much of our contemporary political culture—from rote jingoism as a political defense against corruption to law-breaking ends-justify-means foreign policy to the very idea of “plausible deniability”—had been hatched, emerging from its cracked illogical shell, lizard-like, to stalk the years to come.

Iran-Contra was the pivot. In the shadow of Nixon’s impeachment, it was the moment where America’s political culture and its chattering class alike said, in effect, fuck it. Let’s lie and cheat and deceive, and turn getting caught into a patriotic act. Let’s get into the business of manufacturing our own reality.

3. Welcome to the Occupation

On October 5, 1986, the Sandinista army shot down a Fairchild C-123 cargo plane over southern Nicaragua. Only one of the four crew members, a former U.S. Marine named Eugene Hasenfus, survived (and only because he’d defied orders and brought a parachute aboard). When Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government presented the captured ex-Marine before cameras in Managua, Ronald Reagan categorically denied any connection to the doomed supply mission. “President Reagan, asked if the Administration had any link to it, said, ‘Absolutely none,’” the New York Times reported on October 12.Within days, however, the official denials unravelled in a series of revelations and investigations that became known as “the Iran-Contra affair.”55Even the most common nomenclature—affair—attests to the media’s efforts, from the moment Hasenfus appeared on Nicaraguan TV, to soft-peddle the story. Not a scandal, not a constitutional crisis, not even a gate (though the term Contragate did appear occasionally in the press at the time), but rather a tidy, dirty little affair, over and done with and best forgotten. Hasenfus’ capture was connected to Oliver North’s clandestine airstrips over the border in Costa Rica and from there to a chain of illicit purchases and payouts stretching from Costa Rican shrimp exporters to fly-by-night Miami businesses to Israeli arms dealers and Iranian buyers. Congressional orders had been defied, mistakes—as President Reagan so glibly put it, introducing a generation to the political power of the passive voice—were made. For a good long while, the story dominated the news and seemed certain to doom Reagan to a legacy of corruption and lawbreaking and imperial misadventure. And then Ollie took the stand (and the spotlight, and the fall) in his medal-bedecked Marine Corps uniform, and the buck stopped there and impeachment-scale scandal became an affair.

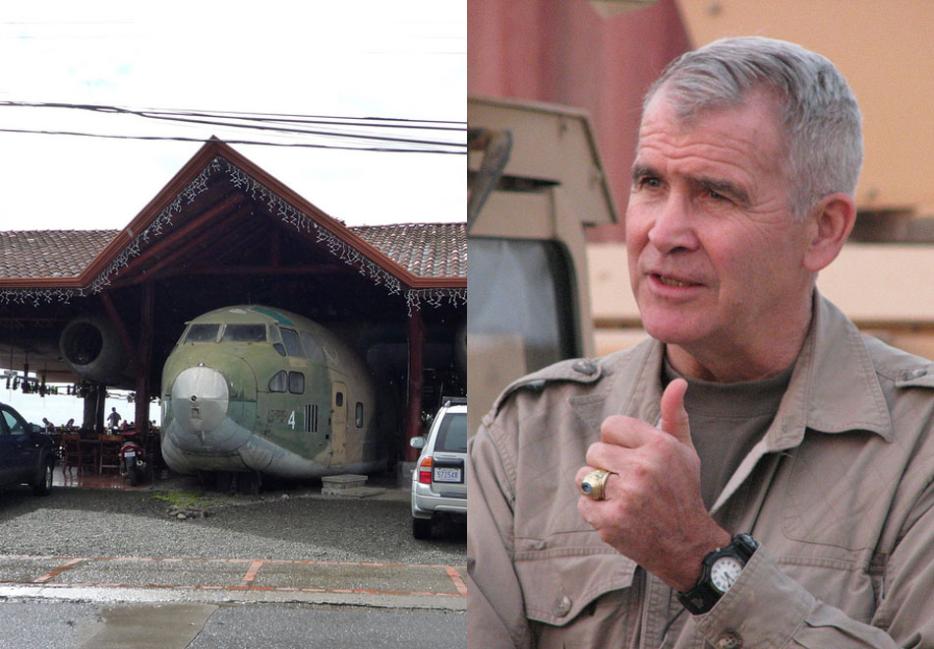

And in the years that followed, watchful visitors to San Jose International Airport might note, on their approach, the rusting hulk of a Fairchild C-123 in an overgrown clearing to the side of the runway. This was the sister to Hasenfus’ doomed cargo plane, abandoned like the airstrips to the north. In 2000, the proprietors of a small resort hotel called Hotel Costa Verde near Manuel Antonio National Park decided to buy the old C-123 and have it dismantled and then rebuilt next to their hotel as the centrepiece of an open-air restaurant. The fuselage, too broad for the old banana-plantation bridges between the capital and Manuel Antonio, had to be shipped to another port and ferried the rest of the way by ocean barge. The plane—whose new owners call it “Ollie’s Folly”—was reassembled on site, its broad cargo hold reconfigured as a cozy bar and the wings stretching out over a wide, canopied outdoor café. They christened it El Avion. It is, to date, the single most tangible monument to Costa Rica’s pivotal role in Iran-contra. I can also attest that it turns out very good pollo con arroz and a pretty decent burger.

I can’t say what it’s like for your average tourist rolling down the highway from the town of Quepos toward the gate of one of Costa Rica’s most popular tourist destinations to see a fully rebuilt C-123 squatting at the roadside amid the low-rise hotels and trinket stalls. For me, though, it seemed like the end of a journey, a strangely welcoming pilgrimage site, a monument, finally, to stubborn, plug-dumb Cold War realpolitik. A place where Dr. Strangelove could meet Clint Eastwood’s campily macho platoon sergeant from Heartbreak Ridge and Patrick Swayze’s Red Dawn junior guerilla troop leader to trade overwrought war stories over cocktails.66Come to think of it, it’s the exact spot I’d most want to meet the Dude’s buddy Walter Sobchak for oat sodas by the tray. This counts as high praise indeed in my personal cosmology. What I mean is it was pure kitsch, and I laughed a lot as I gave myself a tour.

Let’s simply marvel at the fact that Cockburn documented for CBS News in 1987 that planeloads full of drugs were travelling from Honduras to an American military base with enough frequency that the Nick Nolte of the drug pilot set breezed his way off-base at Homestead after delivering 12 tons of pot there.I entered though a door in the camo-painted fuselage with a wooden sign mounted above reading “Pub-Bar El Avion,” and above that I noticed the faded but still clearly legible insignia of the U.S. Air Force’s 434th Tactical Airlift Wing.77The last time the 434th called itself an “airlift wing” was in 1969 at Bakalar AFB in Indiana. It is now the 434th Air Refueling Wing at Grissom Air Reserve Base. It was mid-afternoon, so the bar inside was empty. To the rear of the plane, past a half-dozen high bar tables, a handpainted sign had been mounted reading “CONTRA-BAR.” I don’t know whether it counts as irony or what the hell it says that the bar proudly serves Flor de Caña, Nicaragua’s beloved national premium rum. Out on the café patio, I noticed a wireless modem mounted under the right wing, which gave me a chuckle for reasons I can’t quite pinpoint. Then my daughter stuck her head out of the cockpit window and started doing in-flight announcements in a self-serious captain’s drawl (I’m pretty sure the paramilitary penguins from the Madagascar movies were her inspiration), which gave me a full belly laugh.

What else was there to do? We took a bunch of photos and then we ate. I had a couple of Imperials, and noted for the first time the ironic potential embedded in the brand name of Costa Rica’s most ubiquitous lager.

This is what remains. Kitsch and burgers, a lingering sense of silliness that feels more than a little like whistling past an old unmarked graveyard. It was fitting somehow. If you want to see the last tangible remnant of the brazenly illegal military operation Ronald Reagan’s intelligence services fought for much of the 1980s in Central America—the final doomed proxy war before the Soviet Union’s collapse—well, then, you’ll have to submit yourself to a pleasant tourist-trap meal in a setting stripped of all pretense to august remembrance.

The past is a theme park. Your tour guide is a Fox News commentator, the criminals have all been painted as saints, and there was never any loss so great it can’t be tallied by your server.