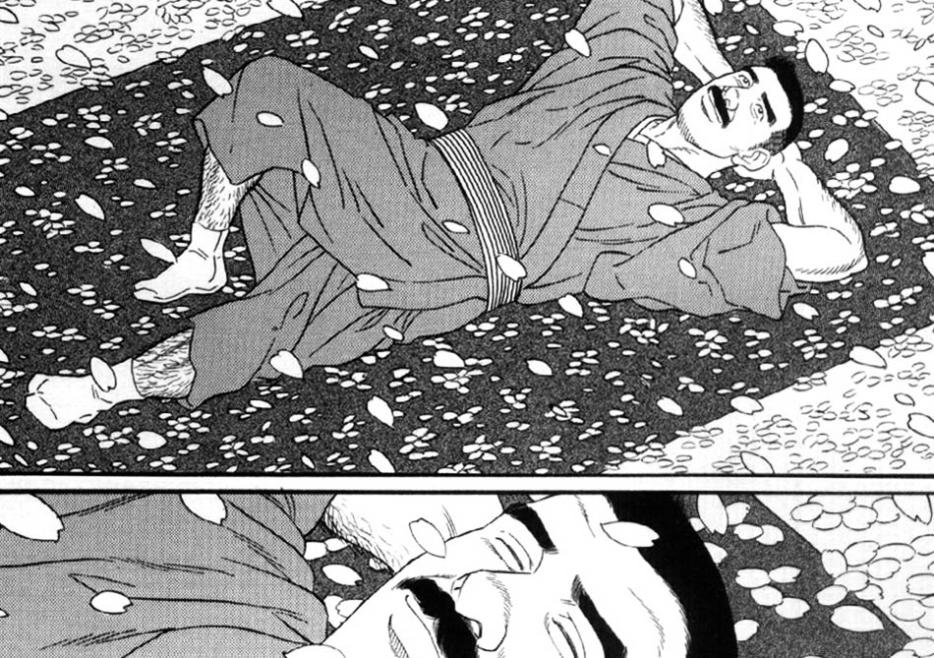

During a trip to Japan in the summer of 2001, the renowned book designer Chip Kidd found himself captivated by some meticulously drawn bondage porn. He was on a tour of gay Tokyo given by his friend Donald Richie, the late film critic and ex-pat memoirist, but these comics were different from the homoerotic manga most familiar to North America, yaoi or “boys’ love,” melodramatic tales of beautiful, intermittently androgynous youths, predominantly drawn by and for women. The male figures were muscular or chubby or somewhere in between. A few looked hairy enough to make Wolverine seem like an alopecia patient. The sadomasochistic tortures visited upon them recalled the classical style and stark grace of traditional woodblock prints, or Robert Mapplethorpe. Buying whichever volumes could pass through customs, Kidd tried several times to contact their creator, this Gengoroh Tagame, but there was no response. He wanted to read the stories of “erotic antagonism” in English; to know, as he writes, “what the heck all these characters are saying (yelling, moaning, pleading, instructing, ordering)…”

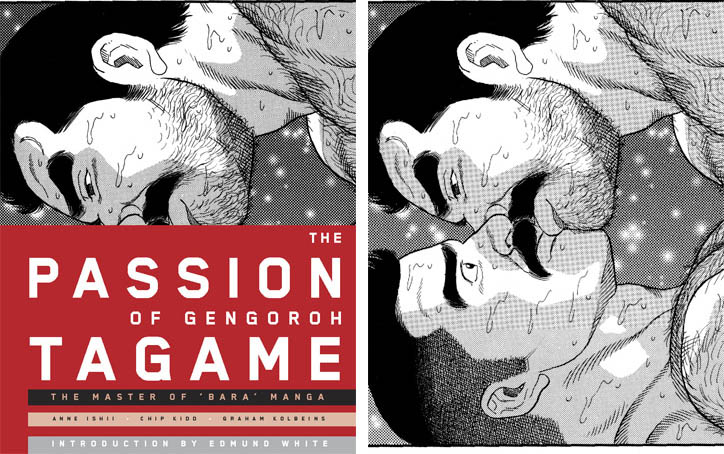

Earlier this month, Kidd sat on a spotlight panel for Tagame at the annual Toronto Comic Arts Festival, where his literary fixation was a featured guest. They were celebrating the arrival of The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, his first English-language collection, which bears a striking amount of prestige and care: released by the influential comics/art publisher PictureBox, introduced by Edmund White, designed by Kidd himself. (The text is literally bound inside the Japanese wrapping called an obi.) Sitting alongside the other members of the book’s production team, Anne Ishii and Graham Kolbeins, he deadpanned that his interest was “purely for scholarly purposes, as a comics historian,” but his admiration for these stories, which he places in the artistic tradition of Pasolini, de Sade, Yukio Mishima and Lolita, was unmistakable. There was a big crowd, and despite Tagame’s near-total association with stereotypically “macho” characters, half of it was female. Several rows back, a woman’s turquoise hair spilled beneath her cap (feathered, not leather). The cartoonist brought together an audience only just beginning to recognize its own existence.

At the same time, others were in pursuit. The young blogger/translator/editor/publisher Ryan Sands had as one of his many projects an erotic comics anthology called Thickness, curated with Toronto cartoonist Michael DeForge. The first issue’s cover, lovingly Risographed, came to exemplify the series and its artist Johnny Negron: a thick, fierce woman, nose upturned, gloves studded, bikini overmatched. “It’s a quintessential large lady looking gorgeous and fearless,” Sands told me. “We wanted to do the equivalent for gay comics and depictions of maleness. And immediately, what is the—it’s not even a polar opposite per se, but what is the mirror reflection of a Negron lady? It’s a Tagame dude.”

As a Japanese-fluent foreign student, he had encountered the bara godhead’s work in an indie manga setting; only after reading a long introductory post by TCAF impresario Chris Butcher did he put a name and a queer-comics context to it. Sands is friends with a lot of people, one being Anne Ishii, and they got the story “Standing Ovation” in Thickness #3 last year before its appearance in The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame. “People talk a lot about the usefulness or utility of porn,” he told me, “and you know, it’s a nice euphemism for what at its essence porn is really about. But people like Tagame and Brandon Graham, some of the early Suehiro Maruo...the work has a pornographic intent, but if they meet those requirements, the rest of the world is wide open.”

The opportunity to enmesh one’s art and one’s labour seems a rare monomania already; what is it like to bring sex into that circle as well? Talking to him through linguistic echolocation, I had the sense that Tagame does not devote his life to his work so much as he allows the latter to shape it. During part of the 1990s, his partner was a gay porn actor, and their first meeting sounds like a fairy tale, pre-sanitization: “When I was doing [historical epic] Silver Flower, I was trying to think of who to base a character on, so I just drew a big picture of that actor and pinned it on my wall…I was self-publishing then, but he had apparently ordered [a comic] and I had apparently not sent it, so like a good stalker he actually looked up my home address and came to my house. So when I opened the door I was like, ‘Oh, this guy looks a lot like that porn star.’ And what’s more, I had just broken up with somebody, so I was free as a bird, I was like, ‘I’m just gonna do everybody and everything.’ So when he was at my door I was like, ‘c’mon in.’ And I had totally forgotten that I had this poster I’d drawn of him on my wall.”

Those strict parents have long known Tagame was gay, yet they never saw one of his stories or even figured out what he did for a living until last year, when they found out his pen name and got to Googling. My family did buy me comics as a kid, but if they discovered that I drew BDSM porn to make rent I’m not sure it would be received with the equanimity that this apparently was. Tagame’s oeuvre and its audience are emblematic of a world where the late 20th century’s rigid categories, those genders or orientations you can count on one hand, fit fewer and fewer lives. In certain cases, they feel like a traumatically false imposition; in some, they just chafe. So it’s unsurprising that bears and girls might both want to read about hairy sadomasochists, that women would tell their creator about reading the manga and having wet dreams—or, as he reports, that “plenty of gay boys” prefer yaoi. (One or two other straight guys aside, my friends at TCAF most excited for the PictureBox collection were all female.) What does seem extraordinary, but maybe also perfect, is how Tagame wriggled a beckoning hand out from porn’s formal restraints. As John Donne put it in a rather different context, “to enter in these bonds is to be free.”