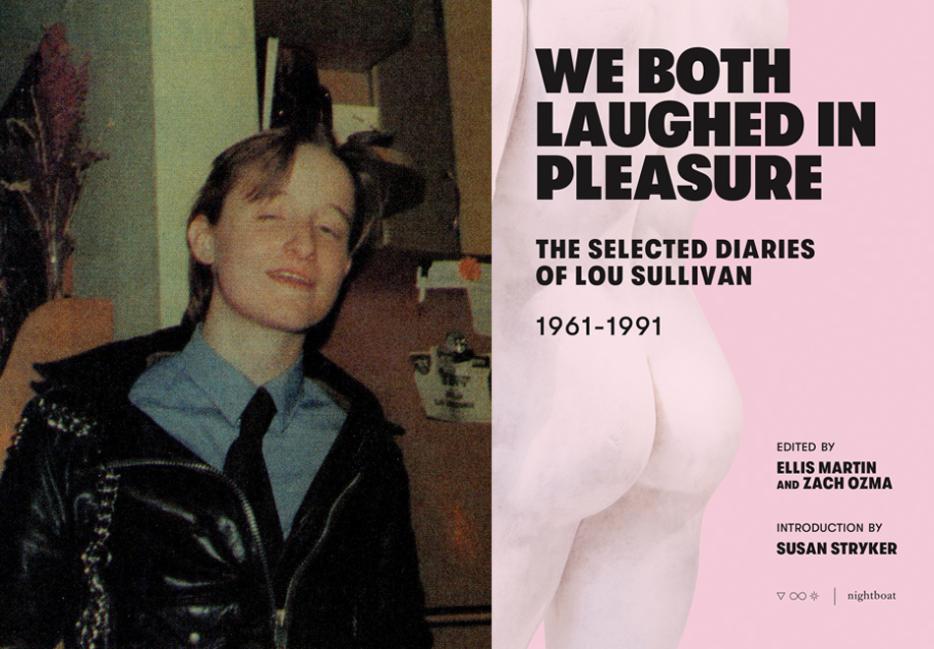

"I was surprised + truly delighted to find the display of affections + feelings going on in these reputed dens of anonymous sex," Lou Sullivan reflected to his diary in 1981. "Somehow those brief displays of tenderness between two men mean more to me than I can say." Sullivan was living as a gay trans man back when few people understood it to be a possibility, and in those journals, published this fall as We Both Laughed in Pleasure (Nightboat Books), he lingers over each passing loveliness: the glitter braided through a boy's hair, the jewelry brushing against his chest. The prose is both frisky and funny, even before he'd discovered Bryan Ferry or Jean Genet. "Mom said to me that it's 'improper' to wave at motorcycles," tween Lou wrote, already mastering the camp flourish. "I'm sure I care!!"

When Sullivan moved to San Francisco in the late 1970s, people like him were barred from medical transition. He campaigned to abolish such rules, a sharpening political focus that led him to gather support groups, piece together archival history, and finally work with other men stricken by AIDS. Doctors scrutinize him; boyfriends capriciously abuse his devotion. But the last entries in We Both Laughed in Pleasure still shiver with joy, a grinning disbelief at remaining alive. One passage describes Sullivan's visit to a gay porn theatre, where a man sidles out from the empty darkness. Not until leaving does he realize that stranger was the ticket-taker—an encounter made lucid only as it ends, like the other side of a dream. I recently spoke with Zach Ozma and Ellis Martin, the editors of Lou's journals, about their process, their interpretations, and why history is gay.

Chris Randle: How did you guys first learn about Lou Sullivan's work?

Zach Ozma: I took this really great class when I was an undergrad and went to California College of the Arts. The class was at Mills College, we had a cross-registration thing—it was with Rebekah Edwards, who's this amazing queer-studies, critical-studies person. The class was on trans poetics, and one week she assigned us two essays about Lou Sullivan, one by Julian Carter that was more theoretical that was called "Embracing Transition, or Dancing in the Folds of Time." And then one was this biographical piece by Susan Stryker that's called, uh—

Ellis Martin: "Portrait of a Trans Fag Drag Hag: The Activist Life of Lou Sullivan," or something like that.

ZO: Something like that, yeah. So that's how I found out about him.

EM: I think I just had a baseline understanding of Lou from being a trans person, and it wasn't until I got invited to do the project that I developed a more in-depth picture of Lou.

How did that develop into this whole project? I had already seen... there's this little mini-documentary about Lou, where he has the bird on his shoulder, but I had never seen the diaries at all.

ZO: After I took that class, I realized that the archive was located in San Francisco, and I was living in Oakland. At the time, it was on a long-term loan to the San Francisco Public Library, so you could just, like, show up, downtown San Francisco, sixth floor, go to the history room, sign in, and look at and touch the actual diaries. So I did a bunch of work about Lou as an undergrad, and then after I left school in 2015 I was talking to my dear friend Zoe Tuck, who's a poet, and at the time she was working with Timeless, Infinite Light, which was a small art-freak poetry press, also in the Bay Area. I actually found the first email about it the other day, and she was half telling me about her day, like, something totally unrelated, then went, "By the way, I'm serious about this book thing, I think you should edit the diaries and Timeless should put it out."

And then we didn't do anything for, like, a year, because everyone had a million projects. Then we came back around and started working on it. I was talking with Emji Saint Spero, who's one of the main people at Timeless, and they were like, how much work do you think this is actually going to be? I was having trouble trying to explain that. I was like, we have to transcribe it, it's all the original diaries, it's not scanned, nothing's happened. I need an intern! So we put out a call for an unpaid intern, paid in book swag and T-shirts, and through that same teacher Rebekah Edwards, who initially introduced me to Lou, I was introduced to Ellis. Rebekah was like, "This student I have is absolutely the right person to do this." And Ellis ended up being the only person who submitted a cover letter. One other person applied, and then she disappeared off the face of the earth. Ellis's cover letter was really good, we met up, he was wearing a little Rush pin on his lapel, and the rest is history.

Like, Rush as in the band?

EM: No, Rush as in poppers [laughter]. One thing I'll say about that story, which I love hearing Zach tell, is that the initial call said something about being able to hang out with weirdos in the library, and asking for a more nuanced understanding of the evolution of queer language. I was interested in that because I went to Mills [College], and being in a place where I was surrounded by a lot of very young, vigilant queers, it felt good to be receiving this call from someone hoping to look at language in a little more flexible way.

ZO: It became clear really quickly that Ellis had the other half of the set of skills that I needed. Like, I had a lot of ideas about the narrative structure and what parts of the diaries I was interested in working with, what type of look and feel I wanted to have the book at, but I had no idea how to get there ... Then Ellis came and made all these systems and spreadsheets and workflows that gave us a way to actually do the project, and we just did, for a really long time [laughs]. Timeless, Infinite Light closed earlier this year, and they looked at a few potential presses to finish the project—this book was their last unfinished one, and they ended up working with Nightboat. There were so many moments when things could have gone wrong, and instead they went really right. Timeless did everything up through the graphic design, which is great, because they were very strong on beautiful books, and then Nightboat has been working with us ever since.

In the editors' note you mention that both of your visual-art practices shaped the book, and I was wondering if you could elaborate on that, like, how did you go about organizing all these disparate entries into a narrative? I was especially struck by how you removed all the dates from everything, I feel like that emphasizes some ephemeral quality...

EM: I will say that we didn't remove all the dates, the chapters are organized [by time period].

Oh right, sorry, I meant the individual entries.

EM: We wanted to give a sense of time, but maybe not one where you read one entry and then you read the next entry and you're comparing the time between the two, you know, as more of a linear timeline. At some point we realized that we just wanted to tell Lou's story in his own words, and all of his early writerly impulses were about telling a good story.

ZO: There was sort of a formal aesthetic reasoning and then also a very practical reasoning that we ended up with, the practical reasoning being that it's a long book, and we got to have more of the actual content if we didn't put the date and "dear diary" every single place where they were originally. I remember this conversation in your apartment in Philly, we were trying to get the page count down, and you were like: "Oh, this is actually useless information that's taking up a whole bunch of line breaks, let's take it out and see how it reads."

It was important to me from the beginning to end up with something novelistic. I've been thinking about that the past few days. As far as my art practice—I studied community arts in school, I do social-practice stuff, and a big focus of that is how to successfully convey information to people who are not in your discipline. I think by removing the date it just reads more smoothly, it's a more fun, accessible book. I know, Ellis, you've had a couple of archival history people miss the dates in the text, and I see that too, but I think it was one of those things where you're like, "This is what our project is and this is what our project is not," and we came down on that side of it.

EM: Our hands are very much on this book, this is not a direct transcription of every diary entry that Lou Sullivan ever had, and the temptation to read it as such with the dates would be even greater. That's related to the graphic design too. We could've given it a boring-ass cover and made it look more formal, but we didn't do that because one of the main audiences we wanted to invite to Lou's world with us were the youths.

ZO: Both of us having art backgrounds, working a lot with combined text and image in our practices, I think that also made some of the design decisions really clear to us. Like including the sort of modified plus-sign / ampersand that Lou uses. Joel Gregory at Timeless made that character, because that's how Lou writes "and."

It made me think of the Prince symbol.

EM: We made a sort of style guide for ourselves while we were transcribing—

ZO: Don't say "we," because it was you [laughter].

EM: I just like order and structure!

It feels appropriate, too, because he was such an aesthete, you know? There's all those descriptions of boys covered in jewels and bracelets. Strict chronology feels inadequate with a lot of his writing.

ZO: At the moment I was getting into the archive, Lou was having this weird time on the internet—there was a little bit about him, he had a shorter Wikipedia page than he has now. I think the Rhys Ernst Grindr video, "Dear Lou Sullivan," was out, and then I think the mini-biography that he did was just coming out, but mostly there was a lot of the Lou Sullivan / Ira Pauly interviews that Megan Rohrer uploaded to YouTube. If you go to YouTube and type in "Lou Sullivan," you'll get maybe seven of them. Ira Pauly was this psychologist who did a bunch of interviews with Lou when he was sick, just recording his life history and transition history and illness. There's a bunch more at the GLBT Historical Society, but there's maybe forty minutes total in short clips on YouTube, and I just watched the hell out of those.

The Lou that you see in there is really goofy and businessy. He's in a bad suit, he's having a weird hair moment, the lighting is crappy and it's like a thrown-together studio, probably in a medical school. And then I would go read the diaries that were really sexy, with a few pictures of him taped in, and you're like, "Oh, wait, this guy was actually a freak, who was really into leather and jewelry and being beautiful." Obviously if you're going to go get interviewed at a medical school and you're a serious guy, you're probably going to put on your suit and try to look regular, but it was important to me that we un-flattened Lou. I think we put an extra emphasis on the sexy stuff because it's so readable, but also because that was his shit, that was what Lou was about!

After I first got the book, I went to Jacob Riis beach, and I remember reading it aloud to my companion that day. It had... a resonant effect [laughs], in the same way. They were like, "This is so hot."

ZO: It's so hot!

I was thinking of the other piece I sent you guys, that essay by Harron [Walker] about the history of the trans memoir, where she says, "it's barely treated like literature—instead, the trans memoir is usually treated as a litmus test for an imagined narrative of progress." And then she cites these writers who are doing more than that, like Janet Mock, Thomas Page McBee, T. Fleischmann. I feel like this book is also many things—it's erotica, it's social history, it's kind of a rock & roll book. Was that on your minds, the weight of these older memoirs shaped by cis agents and publishers and audiences?

ZO: At times, I think. I think it honestly came up the most related to his illness, and to his surgeries, especially his bottom surgery, where he had a lot of complications. We cut down those sections a lot. He was a guy who, if he had a doctor's appointment, he was gonna write down everything that was discussed, the numbers and everything. And we cut a lot of that out, because it started to feel both potentially painful to one audience and too voyeuristic for another. So we definitely drew some lines in that way, but I also think that Lou's writing made it easy to not worry too much about it. What do you think, Ellis?

EM: Yeah, I think absolutely that—like those Ira Pauly videos, we have many examples of cis people interrogating trans people like "here be my freaky pet," or something like that. Since we got to work directly with his materials as trans people, it felt important to preserve all his experiences, but it also felt important to trust our readers, and I think this has been coming up a lot in our conversations. From his fights with his bad boyfriends to his surgery complications, there's definitely moments where we trusted that readers would catch on to the pattern—instead of having this trauma-porn situation of putting too much focus on those things just because they are so weighted, we got to zoom out and retain the idea of pleasure. We've been talking about that word for so long. Part of what we were striving towards for ourselves, and for readers too, is to have something interesting and historical and funny and sexy, which has real interactions that trans people have that are maybe unfavorable or unsavory, but also to circumvent those opportunities for voyeurism.

ZO: One example that I remember making the edit on in the text is, after Lou's first bottom surgery, one of his testicular implants rejected, and there's a lot of detail in the diaries, I would say literally a nauseating amount of detail about what is physically happening to him over the course of several days. And we truncated almost all of that to him, like—he's talking about how good it's going to feel when surgery is done, and how much he wants somebody to play with his balls, and then he goes, "well, ball now." We put in a little bit about him going to the doctor to get another implant put in, but we cut several pages of really detailed personal medical information that I don't necessarily know Lou Sullivan would've been all the way cool with revealing. In some ways you can tell he's writing for an audience, but it's also like, oh, you're literally keeping notes so you can go tell your doctor what happened and when. That's one moment where I think you're able to tell the story, get it across in his words, but you can do it in one sentence instead of five pages.

EM: You also made the decision, I remember, to keep the phrase just as a single "ouch." That was another thing where it was our priority to show Lou having his experience of being in the world and his feelings, those internal moments that are why people read diaries. Or at least why I read diaries, I guess [laughs]. Taking out his documentation and refocusing it on his internal experience.

One vital aspect of the book tracks the change in the medical-industrial complex and its approach to transness, which Lou was instrumental in. My understanding from his own writing and from other historical narratives is that all of these doctors were like, well, gender non-conformity is wrong, and being gay is wrong—but we can square the circle by recommending certain people for transition!

ZO: Right.

So Lou Sullivan showing up and saying, "Yeah, I'm a gay man, I want to align my body with my experience of the world," all of these doctors' klaxons were going off, like, what the fuck is happening, we can't allow this! Do you feel like some of that pathologizing attitude still remains in the medical system?

ZO: In terms of the confluence of gayness and transness?

Yeah. Or transness in general, really.

ZO: Yeah. Short answer, yes [laughter]. I mean, it's not a contra-indication in the DSM anymore, to be gay and to be trans, but I think that there's still a degree of randomness about what clinician you end up with—like, are they super-chill, or are they going to be paternalistic? People still have weird insurance issues all the time. I think part of it is individual practitioners or bureaucrats that have a bee in their bonnet about gender, and part of it is a real failing in those actual systems, that just don't account for the trans subject. You know what I mean? There isn't actually a sanctioned, straightforward way to update your name and your gender marker on U.S. passports. There's things people have figured out where it's like, if you just fill out this form it's good enough, and probably if you get the right person who knows what you mean, most of the time it goes fine, but there's literally no path there. Much like when Lou Sullivan showed up at the gender clinic, there's no box to check that's like, "Are you still going to want to suck dick when you're done?" [laughter]

I think there's still a degree of homophobia in a lot of medicine, especially around what your doctor asks you about your sexual practices. And I think there's an added layer of awkwardness and confusion, and a lack of real medical research too, when you stack transness on top of it ... There still haven't ever been any clinical trials around long-term effects of hormones. There's just a bunch of stuff that nobody's really researched. Anyway, that's my soapbox about subjectivity and the machine of bureaucratic medicine.

I mentioned social history before, and San Francisco in the era that he's writing from there is pretty exhaustively documented, but I was fascinated in that sense by the Milwaukee sections, because it's kind of not. I know that Ellis is from Ohio, but there aren't too many gay memoirs from the Midwest in that era—and Lou had such an eye for social ritual, like, I love the entry where they go to a leather bar, "we're all girls pretending we're bigshot boys."

ZO: Oh, it's so good.

I don't even know if this is a question, but was all that a revelation for you guys in the same way?

EM: Well, growing up in Ohio, I'm pretty aware of the lack of examples [laughter]. It's just something that, for me at least, I have to be constantly reminded how damn persistent the homosexual world is, the scope and timeline. We did a lot of research on early gay bars at the end of the project, to write the glossary, and seeing that there were thriving businesses in Milwaukee starting in the '50s, that's just what Lou encountered in his life, you know? Who knows how long this has actually been going on. It was just a good reminder that there have been weirdos doing weirdo things for a long time.

ZO: I don't know why I wasn't surprised, but I don't think I was. I think it may be because I have hippie parents, so I'm like, probably everyone's gay everywhere [laughter].

That reminds me of a line I keep thinking about, which was said by a star of the official We Both Laughed in Pleasure book launch, Wayne Koestenbaum. He was speaking at, it was the launch for Max Fox's translation of that Guy Hocquenghem book, The Amphitheater of the Dead. And at one point he mused, in a very Wayne K. deadpan, "The past is... kind of gay, isn't it?" Which is really funny, but increasingly profound to me as well [laughter]. Like, the accretion of detail, the search for something desired in these coded passages... "Fellas, is it gay to dwell on a vanished time?"

ZO: I'll send you that Julian Carter essay [on Lou Sullivan], you're gonna jam out on it. He's going into all the root words and talking about being enfleshed in unfolding time.

EM: Something I will never get over about working with Lou, which you touched on before, is that it's kind of a rock & roll book. And I think rock & roll is an interesting example of one of those things that's also in the past and kind of gay. Queen is one of the biggest bands that you hear at sports venues—I mean, I haven't been to a sports venue ever [laughs], but still. Music can simultaneously be really visible and coded in different ways, different circumstances. I think it's something that Lou started to dig into even at an early age, he was obsessed with the Beatles, and then there was Bob Dylan, that's when he started shortening all the words in his diaries. His life shifted every time he found a new, supposedly straight rock & roll role model.

One of my favourite recurring bits is when he's busting out Genet quotes on some glam-rock himbo. It might be overkill, but...

ZO: Lou Sullivan was all about excess, especially verbally [laughter]. He's bringing, like, that Swinburne poem to the friend he has a crush on. I also think, to take it in a sad, bleak direction, we're also seeing the vision of a gay world at this moment, right before the time when so many people died. And it's like, the past is gay in a San Francisco full of alive gay people, when he first gets there. In these theaters and porn stores that are gone. All the gay bars, too. It's a special window that we often get in the big story, the big myth of San Francisco, that day-to-day life.

Have you been in contact with any of Lou's old lovers or family about the book? This is half me wanting to yell at J. vicariously.

ZO: We tried to find both J. and T. real hard, because their full names are in the original diaries. We abbreviated them because we couldn't find them.

EM: In terms of family, his sister Maryellen, who was the person who actually delivered his materials to the [GLBT] Historical Society, one of his closest friends throughout his life, and was with him when he passed—she passed herself right as we were starting this project.

ZO: Like, by the time we went to look her up, we found Maryellen's obituary.

And two of his siblings died before him.

ZO: Yeah. Yeah. Flame [one of Sullivan's brothers] is around, he talked with Brice Smith for the biography that came out a couple of years ago, and we had this moment when we were like... "Do we get in touch with the family?" But we weren't writing a biography, we were editing Lou's diaries, I think that it ended up feeling like it was on the other side of the project. Like, we're only working with these 24 diaries that he donated, that's bountiful source enough.

EM: It was really special, because we had this contract with Timeless, so we got to work with our expectation that this would actually turn into a book, we didn't have to worry about shopping it around, or any intense expectations from publishers. We realized that we could work at our own pace, just the two of us and Lou, and that felt really generative.

I was talking about J. with someone, actually the same person I read this book to at the beach, and we kind of assumed that he's deeply closeted with a family somewhere? Those are definitely the most depressing parts of the book to me, almost moreso than when Lou is really sick, because J. is just so... fickle and manipulative.

ZO: And it lasts for ten years!

Yeah, Lou basically detransitions temporarily for him. Like, J. is pretty clearly at least bi, and as much as I love some self-hating-bisexual representation, it's just so fucked up. It seems like, as long as Lou hadn't medically transitioned, when he could still read Lou as existing in some imagined interzone, he didn't freak out, but as soon as he escapes J's eye in that way it's all over.

EM: Yeah, J. sucks [laughter].

ZO: Yeah. Although I also want to advocate a little bit for the beginning of their relationship—like, they really should've broken up after 1974, call it quits, but there is some sort of intense, beautiful, adolescent exploration that they do together. When he's dressing up J. and imagining that they would go to an event with J. in mink and Lou in leather, or that Valentine's Day where he buys roses for J. and M. and he's like, "I bought flowers for my two ladies." I think there was this moment where they aligned in the same place, that allowed Lou to crack something open.

I think you're totally right, and J. couldn't handle it, he couldn't deal with the implications of that.

EM: Because Lou was really trying to build a world.

ZO: Yeah. J. was okay with having a bounded fantasy.

EM: Sorry J., if you're out there [laughter].

Yeah, what if he finds this and yells at me?

EM: He's not going to yell at you!

Well, maybe he's still hot [laughter].

EM: That's all you can hope for.

Do you know if Lily Tomlin [who was apparently familiar with Sullivan's writing] knows about this book?

ZO: Okay, this is what I've been saying, we have to get her a copy! I don't know where to start. But if you know how to get in touch with Lily Tomlin, I really want her to read this, I'm a huge fan.

There's a retrospective of her movies going on here right now, I wish I'd gone to the opening night and just, like, thrown a copy of the book onstage. Maybe that's a little extra.

EM: Like the rose!

ZO: At one point when we were working on this, Ellis was staying with me for a little bit, and we were just watching Grace and Frankie all the way through, so by the time we got to the part where Lou talks about Lily Tomlin we both were extremely excited.

EM: There's a few [celebrity cameos], like, there's an excerpt I just reread where he sees Christine Jorgensen speak with J., and also goes to see Lou Reed for the first time in the same week. Those are superstars! Really particular in a trancestors way, and otherwise in a freaky-weirdo-baby way. The poignancy of those young interactions with famous people that he has, it's interesting to see it turn around towards the end of his life, he's getting recognized—not at all by the mainstream, but by these few select people. I always think about this—wait, Zach, can I talk about our birth years?

ZO: Yeah, that's fine. I'm young!

EM: So, Lou died in '91, Zach was born in '92, and I was born in '93. It feels like this wild crossing of paths, holding a piece of the people who are no longer with us. Part of them is alive because you have access to their presence, or have had it in the past. Or the fact that Lou Sullivan died on Lou Reed's birthday. There's all these layered interpretations of experience.

ZO: My fantasy now is that Lou gets to become a style model figure, for some kiddo who's piecing together the things.

Is there anything else that you guys want to say about the book, or maybe about the reaction you've gotten to the book?

EM: Copies of the book are going out, people are getting to respond to it in ways that feel a little bit less solicited than with galleys, because that's a more formal interaction. And I had a really nice conversation with Marlo Longley, who we're working with on one of our events; he was just saying that one of his big takeaways from the book... is that people who might be a little less knowledgeable get to see a real-ass trans person from the past. And also specifically cis gay men interacting with gay trans men, there's some cis gay men who have just been in their own bubble, they get to see how hard Lou worked, how welcomed he was in his way, and also sort of not fully visible or present in the world. Getting to that moment where hopefully more gay trans people will get laid [laughter].

ZO: I think Lou Sullivan's already been important to a lot of people, and I'm hearing from a lot of people who are so excited to have this thing you couldn't get unless you went to the archive. And then I also have been hearing from people who are new to him, friends and acquaintances, people have texted me photos of the books they just got in the mail, who I didn't think would even be interested. Someone I know from a totally different context came out to me as stealth trans, and I won't say more about that for their privacy, but we had a really sweet hangout talking about the book. So far it's been this beautiful response.

I got a nice email the other day and had a little cry, because I just think that if Lou were alive, he would be very excited and flattered and also handling it so gracefully. I think he was a little bit born ready to be known. That's part of why he's so good at self-documentation. I'm excited for him to be known, I'm excited for him to be unforgettable, when I think he was really afraid that he would be forgotten, both as an individual and an example of a type of person.

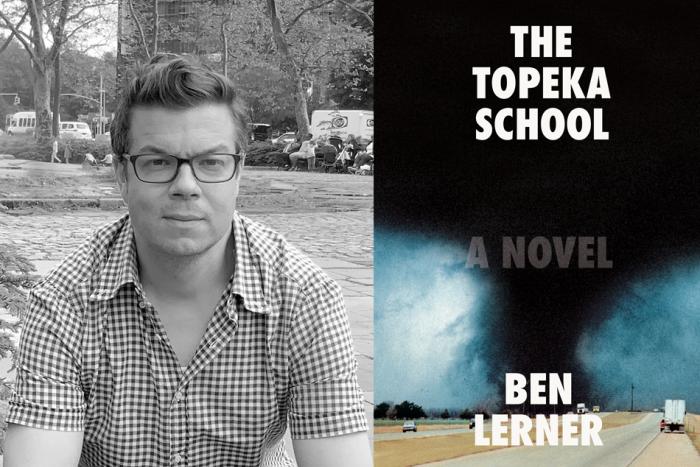

Photo of Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma by Amos Mac.