When Dr. Harriet Lerner, clinical psychologist and bestselling feminist author of The Dance of Anger, appeared on Oprah in the ’90s, there were no online platforms through which viewers could conveniently deliver their abuse. Instead, Lerner experienced it more intimately: through her home phone.

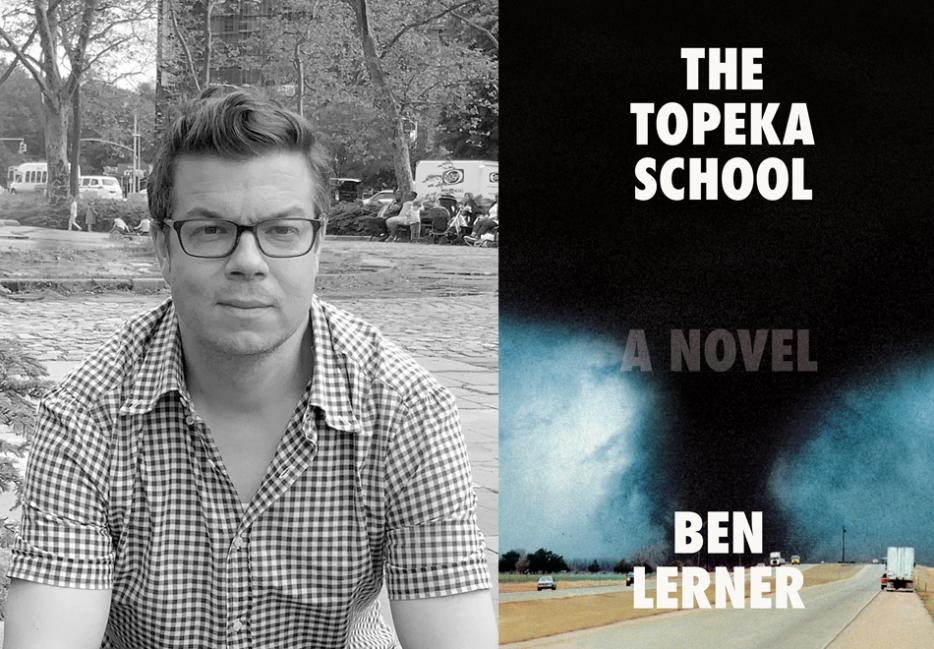

In his acclaimed new novel The Topeka School (McClelland & Stewart), writer (and son of Harriet) Ben Lerner introduces us to Jane Gordon—a Kansas-dwelling clinical psychologist, bestselling writer, and mom of teenaged debate champion, Adam. She too receives disturbing phone calls to the family home, many transferred to her from an adjoining extension by her son. Jane manages the calls ingeniously. Pretending that she can’t hear, she asks the caller to repeat himself, to which he, somewhat bewildered, tries again. Jane repeats the tactic, apologizing for the poor connection. Eventually, the frustrated pervert/menace hangs up, threats ringing in his own ears.

In The Topeka School, Lerner tracks the variegated human voice through a series of intimate dynamics—anonymous phone calls, pleasure craft confessionals, clinical therapy, adult friendship, competitive high school debate, basement freestyle rapping. Sensitive but pitiless, Lerner dissects the language of misogyny, psychotherapy, extemporaneous speech, poetry, family, and most cuttingly, the shifting vernaculars of masculine rage. Within all that—and it is in the best sense all that—he produces a loving homage to parents and the adults who play them, and the radical process by which a mother makes a son.

Periodically interrupted by the hissings of hot milk, I met with Lerner (Ben), who spoke extensively, analytically, and beautifully about The Topeka School, which concludes the trilogy of books that began with Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04.

Naomi Skwarna: Having completed this trilogy, do you think you might leave some of this territory behind?

Ben Lerner: I think so. [Brief pause] I mean, I don’t totally. You know how this book is kind of about familial prehistory and political prehistory? I also wanted to write the prehistory of the other two novels. I think of The Topeka School as the unconscious of the other two books, and that if you’ve read Leaving the Atocha Station or if you read it after this one, then something like Adam’s lie about his mom being dead takes on a different resonance. When I finish any book, I feel like I’m never going to be able to write anything again.

[Terrified chuckle.]

But I think it’s done. When I was in Topeka recently, in part for this New York Times Magazine profile, my family—my brother and my parents—went to the Menninger Foundation campus [where Lerner’s parents had been psychologists]. They’d razed it. There’s nothing there except the clock tower, which was one of the central buildings. Everything else was gone and it’s all covered in prairie grass. I had this weird feeling of like... I was always working towards my Topeka book. Topeka’s mentioned to a certain degree in the other novels, and it’s still my hometown, but [The Topeka School] kind of exorcised this place for me. There was something about standing at that really important site, now overgrown with prairie that was like, very, very—a sense of satisfying completion and totally uncanny bizarre, weird, elegiac…

You’re either going back before it ever existed, or the reality—that it’s gone. Which connects to what you said about it being the unconscious of the trilogy. You draw on a number of different discourses in your writing—poetry, politics, aesthetics—but in line with the idea of the unconscious, has psychotherapy and analysis played a role in your development as an artist?

Growing up, my parents didn’t act like experts. They didn’t claim any kind of authority about relationships. But there was a language about, you know, people would come over and they would end up drawing genograms, where you map out family relationships. So I do think there was a discourse about family patterns, and about the way patterns recur or don’t recur. There was a big belief in talk.

Part of this book is about different regimes of talk. The Menninger Foundation and the household culture were all about talk, and then the masculinist culture outside the house, where if you’re talking—unless you’re talking shit—it’s a sign of emasculation. There are two really fundamental ways where therapy just being in the air—not even therapy as a practice but having that attuned-ness to family pattern and to language in the air—was really important. One was that, you know, works of art are made out of patterns and the recognition of certain kinds of patterning that can give the art object meaning. That’s very similar, in a way, to the work of a family systems therapist that’s looking for intergenerational patterns, and how and what meanings they open up for you.

The other thing is, the kind of listening that good therapists learn, that pressurized silence of therapy, is somewhat related to the pressurized silence of poetry. The idea that white space matters; the idea that real omission is significant. So I think [my parents] were influences in terms of thinking about language and even aesthetic form.

I guess you have no alternative. You didn’t live another life.

I didn’t live another life. It’s funny, because if you would have asked me that question before I’d written any fiction? I think I would have said that language was really primary in the household. Now that I write fiction, kind of despite myself, parents started mattering in the fiction, whether it’s Adam Gordon’s lie about his mom, or in 10:04, how he thinks about being a parent as his friend’s mom is dying. The novels do think about the intergenerational, each book thinking about the intergenerational more. The Topeka School is really intergenerational in its perspective and concern with prehistory. The therapeutic focus on how parents replicate or break patterns that they’ve inherited from their parents has become more and more of a key concern. And that’s a traditional novelistic concern, so it’s a traditional novelistic meeting place between family systems therapy and that mode.

It also feels like you’re writing about that traditional concern.

Yeah. Also, the therapy in The Topeka School is very celebrated in a certain way, like Jane’s different strategies of listening is a counter to a certain kind of weaponized masculine discourse. But it’s also messy and complicated, like the blurred boundaries—

—Yes, between Jane and Sima.

Also, I wouldn’t have written this book if I hadn’t become a father. It’s very much about remembering your childhood from your parents’ perspective, so in a way, it’s also about having to be the grown up, and the realization that there are no grown ups.

The book thinks through regression—in a family, but also regression in collective life, and what happens when you don’t have a loving discourse. What happens in the absence of those sources of meaning? That’s a question that therapists care about historically; psychoanalysis applied to the collective level is what gives people a theory of authoritarian personalities: Trump is a bad father figure. If you look at American politics now, it’s like the Trump/Biden… it’s like a debate between which of the father figures—one is worse than the other—but it is a kind of collective regression about what kind of dad the country needs. They’re both nostalgia for a spectacularized image of the 1950s, right? One is a fascist libidinal discharge and the other is supposed to be a better version of that. The questions about family therapy scale to political issues, too.

An act like writing as a version of the mother or a version of the father, it’s a process of identification. I’m really imagining what it’s like to be that parent, and also dis-identification because you’re no longer imagining those people just as your mom or dad, you’re imagining adults in the world.

Like Jonathan transitioning directly from meeting with Sima to visit Adam in the hospital after his concussion. It’s like these parallel worlds are converging—something that you don’t typically experience as a person, that level of omniscience. What you said about the pressurized silences—I noticed in your acknowledgments that you had thanked [the playwright] Annie Baker. She’s someone who I think of as using silence in a very significant way.

Yeah, I think that’s right. I have a funny kind of relationship to Annie’s work because I read it more than I see it. She’s an artist that I respect who has a very different way of thinking about language and silence, but a related way, so she was a good interlocutor for this book.

You’re such different writers, of course, but when I saw that acknowledgement, I felt some shared psychological concerns.

I don’t know Annie super well, but her mom is a psychotherapist and we’re the same age, so I think there are a lot of affinities and plenty of differences. I’m not very fluent in theatre discourse, I think that comes more from poetry for me, where tactical omission and the backdrop of silence is something that I think we share, as opposed to a certain kind of novelist that’s all about eloquence filling out a whole narrative. I’m much more episodic and interested in a different sense of duration, which probably does have more in common with somebody like Annie. She’s a really interesting writer.

Coming back to family patterns: Klaus seems like such an enigma. He’s a very real figure, but he also has this enormous past as told by Jonathan. He’s very much defined in the present by his past, while also playing important roles in Jane, Jonathan, Sima, and Adam’s lives.

Something that made the real Menninger Foundation really fascinating, and what makes the Foundation in the book, I hope, interesting is that on the one hand it’s this big psychiatric institute in the middle of Kansas. But it also gathered all these Holocaust survivors and displaced Jewish analysts and psychotherapists who had arrived by whatever circuitous route from the disaster of Europe. Klaus represents the surpassing disasters of modernity, the historical trauma. He links the fascist disasters of Europe with the vacuity at the heart of these young boys in Topeka. Jonathan and Jane are displaced coastal Jews, so they are part of the history that involves somebody like Klaus, and also psychoanalysis and psychology, generally. Like, they used to refer to psychoanalysis as the “Jewish science.”

So, Klaus is a figure of European history, Jewish history, and then he’s also a father and grandfather figure. He’s one of the voices in Adam’s head that he tries to access in distinction to his own grandfather’s voice. Klaus isn’t there to say, oh fucked up Midwestern men are the same as fucked up German men in 1939, but he is there as a figure of continuity with a certain history and thinking about authority and regression. The way that collective trauma is inseparable from the history of psychoanalysis as a practice, and psychology as a practice.

Is Klaus based on a real person?

He’s a composite, but there were these Europeans in Topeka. Karl Menninger was really good at recruiting people who didn’t have anywhere else to go. There was a real man, Heinz Graumann, who only vaguely resembles Klaus, but had a similar experience in the Holocaust, and I would just see him around. He had been neighbors with Einstein and friendly with Jung and knew Freud a little. But remember, one of the book’s obsessions is this discourse in the ’90s about the end of history. Klaus is there as a figure of historical trauma, and a kind of ongoing historical trauma, which is about the regression to fascist unreason in these moments of a certain kind of identity vacuum. You can’t always see Klaus. He haunts a little bit.

He does haunt, even in the very different visual aesthetic you give him. He wears linen suits; he’s tall and sort of angular; he gives Adam this box with a secret compartment. There’s a kind of beauty and craftsmanship that he carries with him physically that the other characters, in ball caps and hoodies, don’t have access to.

He has an old-world poise. And a nimbleness—like, he’s always acting and never acting. He’s a figure of a very ambiguous pronouncement.

Yes, like the scene where he does the little performance with the paintings in the cafeteria. He’s an interesting counterpoint to Darren, another haunting character. Darren interests me because he does have this defined voice, but it’s so different from the other characters you’ve written. He’s imbued with your authorial insight, but he’s also himself—a character who seems deficient in understanding. You quite delicately establish his intellectual capacity as being less than his peers. The characters in your novels are always extremely intelligent and educated, and Darren seems quite decisively to be an exception to that. I wondered if he might be seen as a variation of Adam, without parents who care for him, and lacking the merits that allow him to leave Topeka.

I imagine two Adams in this book. There’s the younger Adam in high school, talked about in the third person. Then there’s the older Adam who’s writing the book and ventriloquizing all these other characters. The Darren passages that are very hyper-literary in a certain way. They’re “more Faulknerian” as people keep saying, with a high level of artifice. I think that I was trying to acknowledge the limits of the older Adam’s access to Darren’s interiority. He’s trying to imagine Darren’s perspective, but the book wants to go out of its way to make you remember that those are passages written by Adam. They don’t pretend to have unmediated access to Adam’s interiority or to Darren’s interiority, because I think a lot of fiction isn’t just about being able to imagine other minds—it’s about confronting the limit of your ability to imagine other minds.

Darren doesn’t exactly speak. He quotes some shit talking and at the end of the book he’s mutely holding a sign. There’s some internal language, but it’s very much Adam’s imagination of it.

One of the things the book wants to do is structurally acknowledge the degree to which Darren is a bit of a black box for Adam. And yet, they have all these similarities despite their radical difference in linguistic ability and privilege, because they’re both totally disfigured by this desire to pass as real men. They’re also linked in other ways that they’re not fully aware of, like Adam doesn’t know that Darren is Jonathan’s patient at the foundation, so there’s this way in which they’re kind of like brothers, although with radically different circumstances and capacities. So the older Adam is thinking about his similarities with Darren, in addition to their extreme differences. Adam has all these privileges and modes of support that Darren doesn’t have, and Adam has a lot of guilt about it. Darren is this man-child figure; no community can help them. He can’t be hospitalized—nobody can pay for it—and he can’t quite hold down a job. Then there’s the mock inclusion of him in the social scene, which goes horribly awry. The only family that will have him by the end of the book are the Phelpses, who are these extreme homophobes. He becomes an almost parodic image of masculine terror. He is, to a certain degree, a figure of white surplus rage. The only way to pass as a real man in his estimation is to become this homophobic, violent—it’s random violence, right, in this moment of terrified rage—outsider. But he’s also somebody to whom Adam is really intensely linked.

A defining image that you created for Darren is his moving back and forth through the banner that divides reality and, well, not-reality. Gradually, the divisions fade. It made me think of a line in 10:04, where the narrator, after behaving in an unusual way, thinks “how many out-of-character things did I need to do, I wondered, before the world rearranged itself around me.” Darren’s choices are less conscious, but he seems molded by them. He speaks these lines that he’s borrowed from other people, and they sort of become his truth. The Topeka School, perhaps more than your first two novels, see you going “out-of-character” as a writer. So I guess my question is, do you ever feel like the art, the choices you make in your writing, has the power to rearrange you in some way?

Yeah, it’s a kind of scary thing, actually. Novels are really good at showing how social language circulates through us, the degree to which when we speak, we’re quoting—even in our most intimate moments. That doesn’t mean we have no selves, it just means that’s how language works. We have to make life out of testing this language that’s always already found. Sometimes that’s like poetry, like how in 10:04, the book ends with a combination of Ronald Reagan and Walt Whitman, but hopefully the language has been changed by the experience of the novel.

Adolescence, which is what, to a certain degree, Adam and Darren are both in, isn’t just about coming into a body. It’s about coming into a language and trying to figure out what your voice is. In policy debate and freestyle, Adam is using this language that has basically no application to his experience—talking about how this health care plan is going to lead to nuclear holocaust, or rhyming about the spectacularized image of African American violence he’s gotten from hip hop. On the one hand, it’s ridiculous, and on the other hand, it’s an extreme case of what everybody is always doing, which is trying to make an identity out of collaging in the social materials of language. Both Darren and Adam are involved in that project, and they’re both failing at it in different ways because of the available cultural materials: misogynistic, racist, and evacuated in a lot of ways. Adam has a lot more resources. He has Jane’s voice in his head. He has Klaus’s voice in his head. He has more material to work with than Darren.

Part of what novels are about is showing how individuals are constituted out of these contradictory discourses that are coming from all these different places. This book is very much a genealogy of the voice that’s writing it. How did the adult Adam, who’s writing this book, get his voice? It’s impure and it’s entangled, and at the end in the playground scene, it’s not like he has it figured out. He still has all kinds of busted discourses of masculinity coursing through him. And in part, the recognition that he arrives at is not having figured it out, it’s I have a kind of emptiness and need to learn to speak again. I need to learn to listen again.

I’m trying to write in other voices, [which introduces] a different set of risks for me. It’s intense to write in a version of your mother’s voice about a version of her abusive father. It’s mentally disorganizing. But I felt like I needed to risk that a little more for the trilogy to work. And it’s not like I really knew what I was doing, too. There’s that writing cliché, “write what you know,” but really you have to write in order to discover what you have to write.

Did writing first-person versions of your parents’ voices make you consider or relate to them differently?

Mothers are huge vocal influences. A lot of our voice does come from our parents—not only from your parents—but my mom’s voice has been very influential for me. It’s probably as influential a voice as I’ve had.

Did you read your mother’s writing when you were young?

Not when I was young, but I have read all her books since. We were just kind of similar, like we were more talk-y and similar in a way, and we were both worriers—and talkers about worrying. Writing in that version of my mom’s voice is kind of a midpoint between our voices. It wasn’t about imagining something radically different from me so much as recognizing how much of my voice has come from her. Writing as a version of your parents is also a kind of forensics investigation into your own voice. It’s not about forgetting your voice.

Having kids really changed my relationship to my parents, in the sense that it made me admire and honor them more. Like, wow, they really did their best, but it also made me see them as—now that I’m my parents’ age when I was my girls’ age—it put me more in touch with the fact that they didn’t know what the fuck they were doing, you know? Just like me! They’re doing their best and repeating patterns they only kind of understood, and they were caught up in stuff at work and in their relationships. They weren’t perfect calm adults. There’s more empathy but less idealization; admiration, but also thinking about them not as my mom and dad but as two people with histories and complexity. And doing that in conversation with them about the book. I didn’t write the book and then show it to them and get their blessing. I talked to them about it at every stage.

It’s an homage, but real homage means you have to de-idealize. See these people as fucked up and complicated, too.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.