Commemorations of historic milestones tend to come in two modes: first in a major key, the fanfare that tells us our lives still are defined by the event; then in a minor strain, the elegiac air that implies a past world lost to us.

The assassination of John F. Kennedy has its 50th anniversary this week, predictably attended by reams of think-pieces and hours of television. The dominant motif is The Loss of Innocence from Which the American Dream Never Recovered, but that’s been a cliché since at least Oliver Stone o’clock. So in the past decade we’ve inclined more to the wry melancholy of Mad Men, in which the Eisenhower and Kennedy eras, with their sinister mores but enviable style, become a peculiar, unsustainable prelude to postmodernity: Whatever the trajectories of those slugs over Dealey Plaza, they drew a nearly opaque curtain between then and now.

Oversimplifications, of course. But let me add another: All the talk of conspiratorial causes and epochal effects distracts from the event’s status as a watershed in the history of political murder. Arguably it was the beginning of the end of an Age of Assassination in the western world that had lasted 100 years, since the slayings of Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and the Tsar Alexander II in 1880. It was an era when targeted killings and coups served as the sort of political and cultural preoccupation that mass terrorism and civil uprisings are to us now.

Take the films of Alfred Hitchcock, which return to assassination plots over and over, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and Secret Agent (1936) through Foreign Correspondent (1940) and North By Northwest (1958)—often with an innocent like Cary Grant mistaken for one of the conspirators, as if political murder were so commonplace one could just stumble into it anytime.

As well, advancements in weaponry have encouraged true believers and deranged loners alike to go for the spectacular gesture rather than the selective hit—to fuss less about who is targeted than how many. The dozens lost in Anders Breivik’s 2011 attacks in Norway, for instance, can make one long for the days of lower body counts. But the consequences of single-target assassinations can be equally disastrous.

Indeed, assassination became such a cinematic trope that it started to filter back into real life: Lee Harvey Oswald is known to have watched John Huston’s Cuban-coup-plot movie We Were Strangers repeatedly in October of 1963, and at least one scholar argues it was a triggering experience. And of course John Hinckley Jr.’s whole failed scheme to kill Ronald Reagan was patterned on Robert DeNiro’s would-be assassin in Taxi Driver, thanks to Hinckley’s fixation on DeNiro’s costar, the young Jodie Foster. Today, films such as the Bourne series seem like they’re imitating other movies (James Bond turned joyless), not reality, with rare exceptions such as Oliver Assayas’s 2010 miniseries and feature about the career of leftist mercenary Carlos the Jackal.

I shouldn’t overstate the case. The elimination of leaders and heads of state is as ancient as the Biblical Judith offing Holofernes or the Roman senators taking out Caesar, and as contemporary as the 2007 killing of Benazir Bhutto. U.S. drones and special-forces units still regularly pick off high-value opponents. But today’s assassination action is mainly far away. After the last wave that began with Kennedy and closed with, say, Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro’s snuffing by the Red Brigades in 1978, western democracies have seldom witnessed the successful strikes on heads of state that were an ever-present danger for so long. (The unsolved murder of Sweden’s Olof Palme in 1986 is the outlier.) Four U.S. presidents were struck down in the century from Lincoln to Kennedy, but none since, despite frequent threats and occasional near-misses like Hinckley’s.

Why? Improved security, the end of the Cold War, the stability of the European Union. But perhaps, too, ideologies are less theatrically romantic—even fanatics have less faith in the power of individuals to shape events, knowing each target will just be replaced by another. (Although the fantasy was certainly in the air in the second G. W. Bush term.)

As well, advancements in weaponry have encouraged true believers and deranged loners alike to go for the spectacular gesture rather than the selective hit—to fuss less about who is targeted than how many. The dozens lost in Anders Breivik’s 2011 attacks in Norway, for instance, can make one long for the days of lower body counts. But the consequences of single-target assassinations can be equally disastrous.

The prime illustration of that point has its own major anniversary soon: the centenary of the June 28, 1914, assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The slaying of the expected heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire by a band of Serbian nationalists was the proximate cause of the First World War, and therefore also the Second, and thus the whole world we know.

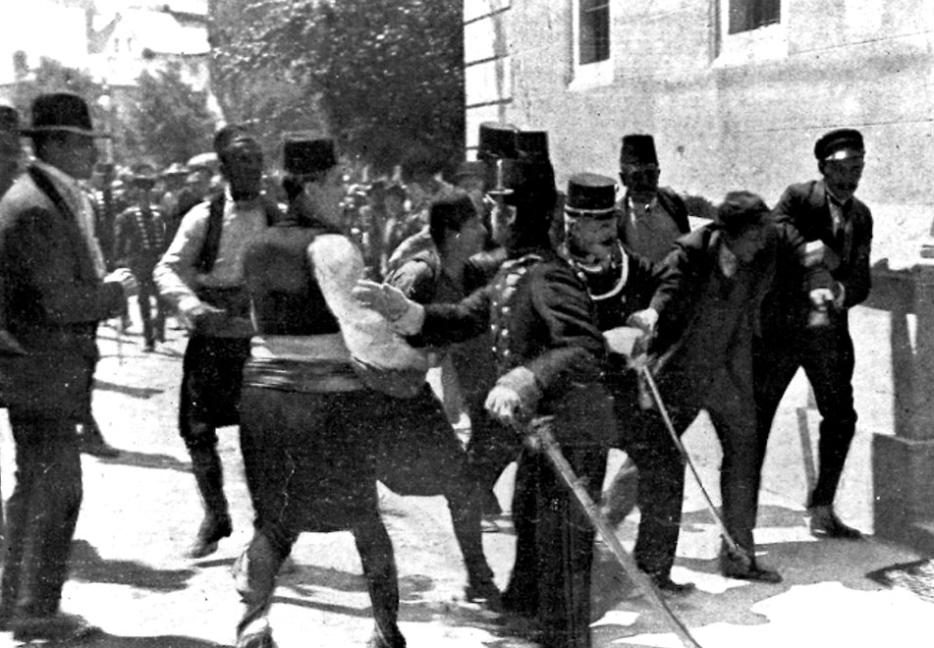

What’s eerie is how these twin peaks of the Assassination Age, in Sarajevo and in Dallas, are funhouse mirrors (without the fun): If Oswald’s action was too tidy to be true (unless it was also a mistake), Serbian shooter Gavrilo Princip’s was too messy to credit. As podcaster Dan Carlin pointed out in last month’s edition of Hardcore History—basically like a seminar taught by your best-read stoner friend—each killing centered on a state visit in a motorcade, the dignitary beside his wife in an open car. But in the Archduke’s case, it is as if Oswald had missed his shot, packed up his rifle in frustration and gone across town for a sandwich, and then Kennedy just happened to drive past him again.

Princip’s fellow conspirators missed with their first bomb and were forced to scatter, but rather than leave town, Ferdinand then decided to go to the hospital to visit the wounded. When his driver made a wrong turn and the car stalled in front of the very food shop where Princip was laying low, it presented an unplanned second opportunity. In two hasty shots the teenaged rebel killed both the Archduke and his wife. Now, those were some magic bullets.

The arbitrary course of the killing falls into a long list of ironies and what-ifs—for instance, couldn’t Vienna have been content to prosecute the perpetrators rather than attack Serbia and set off the domino tumble that led to total war? But Carlin answers that question with another: Can you imagine what would have happened if Lee Harvey Oswald had been proven to be an asset of the Soviets, the way Princip’s Black Hand group was almost certainly connected to Serbian intelligence? It actually conjures up a whole alternate conspiracy theory: If there was a cover-up after 1963, maybe it wasn’t to conceal corrupt collusion but to avert a confrontation that could have led to another world war, this time with nukes.

Given the weight of the Archduke’s murder, it’s remarkable how seldom it’s been depicted in art. Perhaps its fundamental ridiculousness weighs against it, or the more horrific absurdities of the war itself—the great subject, overt or subliminal, of early 20th-century art, music and literature—simply overshadow its instigating event.

Consider what happened after anarchist misfit Leon Czolgosz shot imperialist U.S. President William McKinley in 1901: Congress passed the Anarchist Exclusion Act, for the first time barring immigrants on the basis of their beliefs. Then again, anarchists made a major contribution to the early Assassination Age with their idea of “propaganda of the deed,” which spelled doom for a score of monarchs, judges, prime ministers, and other officials between the 1880s and the 1920s. Jack London’s thriller The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. reflected that atmosphere, begun in 1910 but not published until it was completed by another author in, ahem, 1963.

Given the weight of the Archduke’s murder, it’s remarkable how seldom it’s been depicted in art. Perhaps its fundamental ridiculousness weighs against it, or the more horrific absurdities of the war itself—the great subject, overt or subliminal, of early 20th-century art, music and literature—simply overshadow its instigating event. I could find precisely one notable film, the 1975 international co-production The Day That Shook the World, in which Christopher Plummer plays Franz Ferdinand, but by all accounts it is plodding and literal.

The greatest novel of the decline of the Hapsburgs is Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, which depicts the muddled and chaotic thinking at the top of the empire in both blackly comic and existentially abstract tones. It’s set in and around court life in 1913, but never sets up the war as an inevitability—it keeps the calamity like a secret, just one possibility among many, which might be why Musil was never able to finish the final volumes of the book. But even in more conventional historical novels such as Joseph Roth’s epic The Radetzky March and Mikos Banffy’s Transylvanian Trilogy, the Archduke’s assassination always seems to take place far offstage.

The contemporary Bosnian-American writer Aleksandr Hemon, does portray Franz Ferdinand’s death directly in his short story “The Accordion,” but deliberately gets all the details wrong, for instance situating the aristocrat not in a car but in a horse-drawn carriage: “the Archduke can see the horse’s anus slowly opening, like a camera aperture…”. The narrator confesses to mangling the story, apparently as a form of revenge for his great-great-grandfather, who played the accordion for those festivities in Sarajevo but would soon die of dysentery in the First World War.

Again and again, then, the event defies representation. It is too grubby to bother with and too huge to fathom. Novelists such as Thomas Pynchon (in Against the Day) and E.L. Doctorow (in Ragtime) have had fun with the fact that Franz Ferdinand once toured America, spinning counterfactual yarns out of his visits to the Chicago World’s Fair and Buffalo Bill’s rodeo show. They both portray him as a dim-witted imperial naïf: When the Archduke sees Harry Houdini give a stunt-flying demonstration in Ragtime, he confusedly congratulates Houdini on having invented the airplane.

Years later, after the killing, writes Doctorow, “Harry Houdini, reading his paper at breakfast, felt the shock of the death of an acquaintance. Imagine that, he said to himself. Imagine that. He saw the moody and phlegmatic Duke staring at him from under his coif of flattened brush-cut hair. It seemed to him awesome that someone embodying the power and panoply of an entire empire could be so easily brought down.”

And maybe that’s all that “assassin” really means now, years out from the Age of Assassinations—having skills, being able to “kill it” metaphorically on the mic or the court or in the sheets, whatever your field of battle.

Gavrilo Princip is even more absent from the cultural canon, despite the fact that his Black Hand/Young Bosnia circle was actually as literary as it was political. One of his indicted collaborators, Ivo Andric, would even go on to win the 1961 Nobel Prize for Literature. Princip himself was a devotee of Nietzsche and of Walt Whitman, which led the great Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz to quip in his 2000 collection Milosz’s ABCs: “The young revolutionaries in Belgrade read [Whitman] politically as a singer of democracy, of the crowd en masse, the enemy of monarchs… and that is how an American poet was responsible for the outbreak of World War I.”

But the great eulogizer of Lincoln—“O Captain! My Captain!”—was no longer around to record Gavrilo Princip’s deed. The only poetic tribute to the quick-thinking young killer I’ve ever stumbled across is in Canadian rapper Cadence Weapon’s song “Black Hand”—“style soft like a pillow/ for real though/ black hand like Gavrilo.” It’s a particularly clever variation on the hip-hop figure of the “verbal assassin,” as Nas called himself in a name-making 1991 freestyle.

And maybe that’s all that “assassin” really means now, years out from the Age of Assassinations—having skills, being able to “kill it” metaphorically on the mic or the court or in the sheets, whatever your field of battle.

When I type “assassin” into a search engine, the first auto-filled suggestion is Assassin’s Creed, the massive-selling video-game series in which, in different editions, you can try to commit or prevent killings related to the Knights Templar, the Borgias, and the American Revolution—though not, so far, the Archduke or JFK. (That’s been tried, with a game called JFK: Reloaded, and it did not go down very well.) These modules of history become a bit interchangeable, the way that Mick Jagger’s sprite of misrule moves through centuries from verse to verse—“what’s troubling you is the nature of my game.” Perhaps a little sympathy for the devil is what the romance of assassination can draw out of us.

On the walls of his prison cell, Princip is said to have scrawled these defiant lines of poetry: Our ghosts will walk through Vienna/ And roam through the palace/ Frightening the lords. But in the end, down the decades, the 19-year-old’s act outside the sandwich joint left no more functional palaces in Europe for his spirit to spook. He had killed time. His gun was a camera. The camera is an anus. There was the blast and then the shit, a jump-cut and then a book depository, and then a first-person shooter who is you and me—black hands on the remote, changing social stations, acting alone.