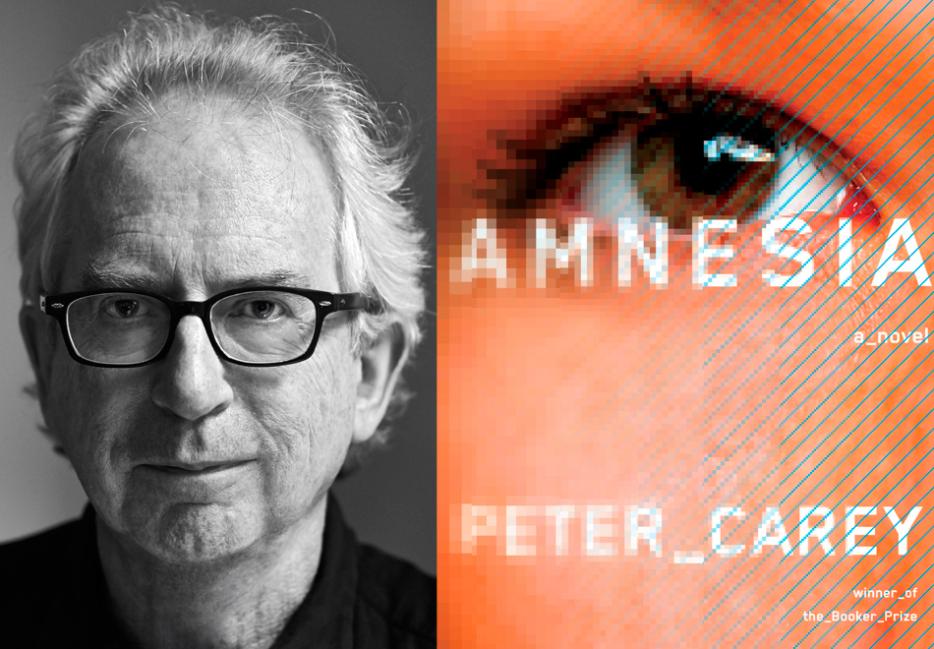

The works of Peter Carey span continents and centuries. He’s equally adept at precise descriptions as he is at navigating situations where ambiguity is the dominant mode, his novels encompassing everything from meditations on identity and forgery (My Life as a Fake) to subtle riffs on Dickens (Jack Maggs) to investigations into a historical automaton juxtaposed with the collapsing emotional life of a horologist (The Chemistry of Tears). Carey’s latest novel, Amnesia, seems almost deceptively simple: Felix Moore, a disgraced left-wing journalist, is commissioned to write the biography of Gaby Bailieux, a hacker and activist, whose actions trigger the release of numerous detained immigrants and criminals throughout Australia and the United States.

From there, the story plummets through histories both personal and political, including Felix’s reflections on a half-century of Australian history, as well as Gaby’s family’s complex and sometimes horrific past. Even as the contemporary scenes illustrate the fraught relationship between Australia and the United States, flashbacks accentuate it, showing American troops clashing with Australians in the early 1940s, and referencing the CIA’s involvement in the events of 1975, when Australia’s Governor-General removed the elected Prime Minister from power.

I recently spoke with Carey over the phone, our conversation ranging from Amnesia to technology and historical memory. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Tobias Carroll: In the background of Amnesia, you chart the history of the Internet over several decades, from dial-up connections and BBSes through to the present. Is this something that you’ve had an interest in since those early days?

Peter Carey: I had no interest in it all, but it’s amazing what having an idea for a novel will force you to do, and the worlds that you will enter. You’ll have to learn to be convincing to people who know those worlds really, really well right now.

I had some guides. I had a guy at Google whose preferred form of reading is science fiction, but who read this manuscript three times and gave notes for certain things, telling me, “That’s impossible; you can’t do that.” I’d say, “Well, if I wanted to do that, how could I?” He’d say, “Well, you could do that.” Et cetera, et cetera. He read the book three times, which was very generous of him, so I know it will stand up to that sort of reading.

I teach at Hunter College in New York, and there’s a professor who specializes in artificial intelligence. She was of the right vintage; she wrote a couple of paragraphs of code for me in Lisp, which I’m very grateful for. When I’m going into something that is not my original territory, I want to make sure that it works for the people whose territory it was.

Is this the first time you’ve had do this much research when writing about a contemporary subject?

I’m going through the things I’ve written that were set in roughly present time: Bliss was, but there wasn’t a lot of research in that; Illywhacker covers a period of history, some of which was contemporary at the time of having written it. I never really think about work as being historical or in the future—it’s as stuff that’s made up. I wouldn’t normally distinguish between science fiction and a historical novel.

There’s a very contemporary, relevant plot in Amnesia about geopolitics and surveillance and detention, and there are also more historic elements, whether it’s the parts relating to World War II or the events in 1975, or the personal histories of these characters themselves. Did one of those elements in particular come to mind first?

I always think of the present as being an expression of the past. We wouldn’t be in the present if we hadn’t had the particular past that we had. To me, they’re all part of the same chain, if you like. The past is never the past; we’re living in the consequences of the past right now.

The thing that has always engaged me is the overthrow of the Whitlam government in 1975. It’s a story that can be told from what we might simplify as the Murdoch point of view, which was the Murdoch point of view at the time that it happened, and the Australian press’s point of view, which is that nothing bad had happened, and no one had done anything wrong, and that this was part of the normal parliamentary process, which it wasn’t. And we can now be confident that the CIA had every reason in the world to assist in the overthrow of this government. And the fact that the United States can now use drones in Afghanistan is because there’s a base in Australia that was one of the big points of argument at the time. To target those people on the ground, that’s the Pine Gap base, and the United States was not prepared to do without it.

The fact that the elected government of Australia was overthrown, as so many governments have been, by the United States and its agents, still upsets me. Telling this story, I expected that I’d come back to Australia and I would have to put up with a great deal of resistance to the narrative. Instead, what I found was that... We have the Australian Broadcasting Commission, like the CBC or the BBC. I was on something like 11 ABC radio stations and three or four television stations without encountering any serious opposition to my historical assertions in the book. There was one, at the very end, which was a politically generated one. Generally, people liked the book, responded to it, accepted it, and the story is in the Australian narrative once again.

Your books are read throughout the world, but I would assume that an Australian reader would be more familiar with these events than someone in the US or Canada or even Great Britain.

Absolutely.

I remember hearing about this happening, but I had to pause my reading a few times to look up some background on these events.

I’ve just started to re-read Balzac’s Lost Illusions. When Balzac was writing that, he wasn’t thinking that you or I were going to read it. He wasn’t trying to explain French history, or things that even the best-educated of us have forgotten. I think we get too tense about what we have to know, and when we read from another period, we accept that. We can do two things about it: we can go out and get history lessons, or believe that in the end, the story will carry us there, and we shouldn’t be anxious about those things.

I think this book is written so that if the reader would relax and trust me, it’ll be all right. I think the only thing that might be occasionally destabilizing for American readers is that, of course, the story has a great deal to do with them; it has a great deal to do with the United States and the CIA. They have to believe that I’m telling the truth, and that I’m a reliable person. And then they have to know, somehow or another, what they’re going to do with that information, and I think that’s difficult. I’ve told this story to my New York friends over the last 25 years—they’re always shocked and upset. So it places a particular load on the American reader, and the American reader will respond in whatever way their personality dictates, I guess.

In the novel, you also discuss conflicts between American and Australian soldiers during World War II. Do you find that’s another thing not as widely known outside of Australia?

Even within Australia—it’s no longer a secret, although it was a secret in wartime, of course. I don’t know when it became more widely known, but certainly in the period when it occurred, it wasn’t known at all. My experience of Australian readers, the young ones particularly, acknowledge that they knew nothing about it, like you knew nothing about it. It’s significant for me. We have a narrative here that we have enormous friendship and trust and cooperation between Australia and the United States; the truth on the ground was somewhat different then, and the truth was not told. That’s really why it’s there.

This novel has a realistic, historically informed view of U.S. politics and U.S. political influence. I’m thinking back to The Unusual Life of Tristan Smith, where America also loomed large, but in a very different, much more surreal, fashion—

With its roots in the same event.

Do you see the two as being in dialogue at all?

At the time that I wrote The Unusual Life of Tristan Smith, I’d just moved to the United States. I really wanted to engage with the coup of 1975. I didn’t really see the point of doing a realistic novel about it, at that particular period, so I did what I did. In the readings of that book, which are different from country to country, the interesting thing was how many of the American readers identified the culturally and militarily dominant country of Voorstand as not being the United States—American readers tended to identify themselves with the small revolutionary. I was reading it in Toronto, [and] from the first lines of the thing, the audience knew exactly what I was talking about, and were roaring with laughter. Things operate differently, in different ways. That slightly strange book certainly did come out of my feelings about 1975.

The first half of the book is a first-person narrative, and in the second half, different narratives shift in and out of one another.

The second half, of course, is the book he’s been commissioned to write. Felix’s character really grows out of my desire to have a writer who could write this in first person, and then later, write it in third person. Felix is the way he is because of his ability to be a little... He can report something that he didn’t personally observe. The fact that the book begins with his court case for defamation has a lot to do with me preparing a character who’s going to be equipped to, and want to, write the second half of the book, if that makes sense.

Did you have any real-life role models for the kind of journalist you wanted him to be?

The Felix sort of journalist, people in Australia and, to a degree, the United Kingdom certainly recognize. Not that I’m suggesting he’s a stereotype, but we all knew people who are a little like that in one way or another. I myself think about Felix with enormous affection. I think he’s ridiculous, and I think he doesn’t always tell the truth, and he’s often cowardly and opportunistic, but I feel huge affection for him as well. And I’d like to think that his antics were occasionally funny, and that one might have some heart towards his situation.

I thought that the balance between the sometimes contradictory elements of his character was very readable.

It’s not a white hat/black hat kind of situation. He’s definitely a grey hat.

Both Amnesia and The Chemistry of Tears are books that have narratives that are told through different layers of time. They have very distinctive first-person narrators—two, in the case of The Chemistry of Tears. And each deals with technology, in its own way. Did you find that writing one informed the writing of the other?

Presumably, one’s present is always informed by one’s past and what’s done before, ideally, and it gives you the ability to deal with the future. When I was writing it, it never occurred to me that they had any relationship to one another at all. Which doesn’t mean that your observation isn’t totally correct, and that they do have relationships to one another. But they’re not things that I was aware of when I was working.

As for the different points of view, I think that if one began with Illywhacker and went through Oscar and Lucinda and books from longer ago, the thing of adopting the points of view of different characters—Oscar and Lucinda is full of different points of view, many different points of view of many characters. That sort of fractious or even Cubist view of reality seemed to me to make a more complicated truth. I’ve done that a lot. With a couple of books, clearly with The Chemistry of Tears, it seemed like two voices would make this work. I’m trying to find different ways to accommodate differing points of view, because that’s when things get interesting. Mostly, in The True History of the Kelly Gang, I couldn’t do it.

Earlier, you had mentioned that you had reached out to different experts for information on the early days of the Internet and coding. How do you go about finding someone who can give you that kind of information?

One of the most valued and trusted teachers when doing this book was a guy who must remain anonymous, who worked at Google. I know him because, I’m going to the physiotherapist, who I’m telling about the book, and he said, “Oh, my other patient is so-and-so, who works at Google.” I said, “Do you think he would talk to me?” And he said, “I think so,” and that happened. It’s not like I didn’t ask many, many people. In the case of Susan Epstein at Hunter College, I think I was talking with our president, and she said, “Oh, you’ve got to talk to Susan Epstein; I’m sure she’ll be helpful.” And she was great! And she was a reader. Both of those people are readers; the Google guy is a science fiction reader, but a reader, and Susan Epstein actually knew my work. They were both incredibly helpful, generous informants. In the end, I think you find the people because you need them, and you keep asking because you want to be fed.

How long after you’d finished The Chemistry of Tears was it before you began Amnesia?

Not very long. Once I’ve finished a project, I really do like to know what I’m going to do next, even just to calm me down a little bit. I normally finish not having an idea in my head, and being used to being busy, and not being good at doing nothing. I do believe, from memory, that I had two different attempts at different books, which I thought would be interesting. Then they felt shallow to me; there wasn’t enough to sustain me. After a couple of those things, I had a lunch with Sonny Mehta at Knopf, and we talked about Julian Assange. The day after that—because I’d been talking about Australia and the United States and 1975 and politicians calling Assange a traitor, when he was an Australian—I began work on this book. There’s a very particular correspondence between that conversation and the beginning of the book.

In terms of the events of 1975, are there books that you’d recommend to a reader outside of Australia who might want to know more?

There’s one book—the whole book is not about 1975—by John Pilger from 1989, called The Secret Country. His stuff on 1975 does the job. There’s much more reading to be done, of course, but that would be a really useful extraction for anybody. Also, go to Netflix and get John Schlesinger’s film The Falcon and the Snowman, which is Sean Penn and Timothy Hutton, in which Timothy Hutton plays Christopher Boyce, a young American from a very patriotic family, working for a CIA contractor, and discovering what America is doing in Australia at that time. It leads him to be violently angry with his country, and with the CIA, and to do a number of silly things. It does authenticate, from an American perspective, what could be called allegations that are at the foundation of this book.

You’ve been teaching at Hunter for a while, and I’ve seen a couple of short pieces that you’ve written about that experience. Do you think that teaching fiction has had any effect on your own writing?

It’s the work of a fiction writer, in my view, to imagine what it is to be other, to be someone else. The class should be an active entity with the other writer. You don’t want to control the writer and get the writer to do what you do. You’re there to think about how they might do what they want to do better. To be engaged in that continually has to be helpful. And in terms of thinking about how literature works and explaining it: if I’m going to critique a piece for a class, I might say something that none of them expect, and I want them to be able to see that it’s credible. There’s a certain intellectual rigor that’s required in that. In a more general, human way, I think it does a lot of good to be thinking about people other than ourselves. It’s a very, very selective group: To bring in six people to the class every year, we read 450 applications, so these are very, very smart people. And they’re not babies, either. I feel very nourished to be in their presence, and I’m very pleased to help them. We have a great faculty, and they feel the same way.

Both at the beginning and the end of the book, there are references to a screenplay adaptation of Felix’s novel. Is that a nod to your own experiences having works adapted for film?

I was thinking of the thing of a writer of a certain age, where money’s been an issue but he’s also had a lot of ambition, and he’s still on the periphery of literary life. When he’s telling you what he’s done, he’s going to tell you that he had some presumably farcical or satiric work workshopped at Sundance, which for him is a very, very big deal. It was more talking about his relationship to literary fame or fortune. The last line of the book from him, that it’s soon to be a motion picture, I almost didn’t put in. I thought it was, maybe, a little too light, but I kind of liked that he’d had the film made.

It seemed like something of a happy ending for him.

Given that his history is not one of great success. His work itself has become a part of a cybernetic arsenal. And the result of that is that he’s gone on to sell a lot of books, which we couldn’t have ever expected of him. What can I say? I enjoyed it. I enjoyed doing it for him.

Throughout the novel, Felix seems resistant to doing whatever anyone asks him to do; he’s always warning people that he’s not going to do what is expected of him. How do you write a character that almost refuses to take part in the plot that’s set out for him?

I like the notion that the character’s in rebellion against the author. Felix is, after all, a journalist, which is by definition a very different thing than being a fiction writer. Certainly, the fiction writer part of me is all about issues of control. I’m like a small shopkeeper or a taxi driver—"If you don’t like me, get out of my fucking shop!” I think that’s a privilege, sometimes a mistaken one, that fiction writers can adopt. Maybe I gave Felix some of that. I did want to make him willful and wary of control, but forever being dependent upon people, it seems.

There was that give and take, where he’s utterly dependent on people for certain things, but he needs to have some sort of agency over what he’s doing.

That’s an important element of how he would see himself. In those battles for agency, he’s sometimes going to lose, he’s sometimes going to win, and he’s sometimes going to lie to himself. It’s his drive.

Felix shares a lot of history with some of the other characters in Amnesia. Was all of that there when you started to write the novel?

I did think, when I first started writing the parts where they were young and at university, that those characters were going to have a role in the future. As I went backwards and forwards over it, certain of their characters... It took me a long time to feel like Sando was right. I didn’t really know exactly who he was, and I didn’t exactly know what the relationships were going to be. I didn’t really know that I was setting out to produce this perfect set of self-obsessed Boomer parents, who were going to neglect their child. Those things, I discover as I go along, and then work on them and refine them and change, change, change.

I wanted to talk briefly about the sense of place. Did you go to different places around Australia, or did you already know the settings that you planned to use?

Yes, yes, and yes. I lot of them, they aren’t there any more. Time removes these things from you. If I went to Monash University now, the thing that I was writing about wouldn’t be there. There would be nothing there to make you think that it had been there. There were some things that I checked on. I had a very pleasant excuse to go to Australia to do quite a lot of work around Coburg, which is a suburb I only knew in passing. And I had a wonderful time doing that, and I made a lot of good friends with people who had been teachers at Coburg High School. I went there quite late in the process, talked to a lot of people, a guy and his wife who’d been principals at an alternative school rather like the McKenzie Community School. And all of these people, I gave them the manuscript in the hope that they’d find something I’d done that was wrong and would tell me about it. Actually, there wasn’t a lot to change, but I was very pleased to show it to them. It was thrilling when the book came out in Australia; a lot of people felt that the voices, places, and everything were right. I didn’t know whether to be thrilled or hurt: people were astonished that after 25 years in New York, I could still write about this place in a way that they recognized. That was nice for me. I was thrilled by that.

Do you have a sense of where your next book is going to be set?

It’s going to also be set in Australia, and the period will be around the 1950s, and that’s about all I want to say about it. It’s something I’m very excited about, and it’s a big deal for me. It’s something I’ve wanted to do all of my life, and never thought there’d be a way to do it, and there is.

Are there any cities or countries where you haven’t yet set something, where you’d like to?

I don’t really think of those. I’m led to things by issues, if you like. Novels that end up being memorable, really, because of characters, don’t start out like that. I don’t know those people at the beginning. The ideas begin in a much more theoretical sort of thing, almost like a cartoon. I do remember writing Oscar and Lucinda and realizing that I was going to have to set part of it in England, and in the 19th century, and really, really not wanting to, but there wasn’t a choice. The idea demands that it be done like that, so you go there. I didn’t go there because I was drawn to writing about the 19th century, which I really didn’t want to do, because I thought I didn’t know how to do it.

You’ve written several novels now set at least in part in the 19th century. Is that something that you see yourself returning to again, if the issue was right?

If the idea leads you there, and if you’re interested in the past’s effect on the present, and how the present sees itself, and how the present acts, then often, you have to go back—it’s a question of how far you need to go. So it could produce it. Am I madly keen to do that? Not particularly. On the other hand, when I finish the next book, I don’t know what I’ll do next. If I have an idea that’s interesting, I’ll grab at it and not let it go.