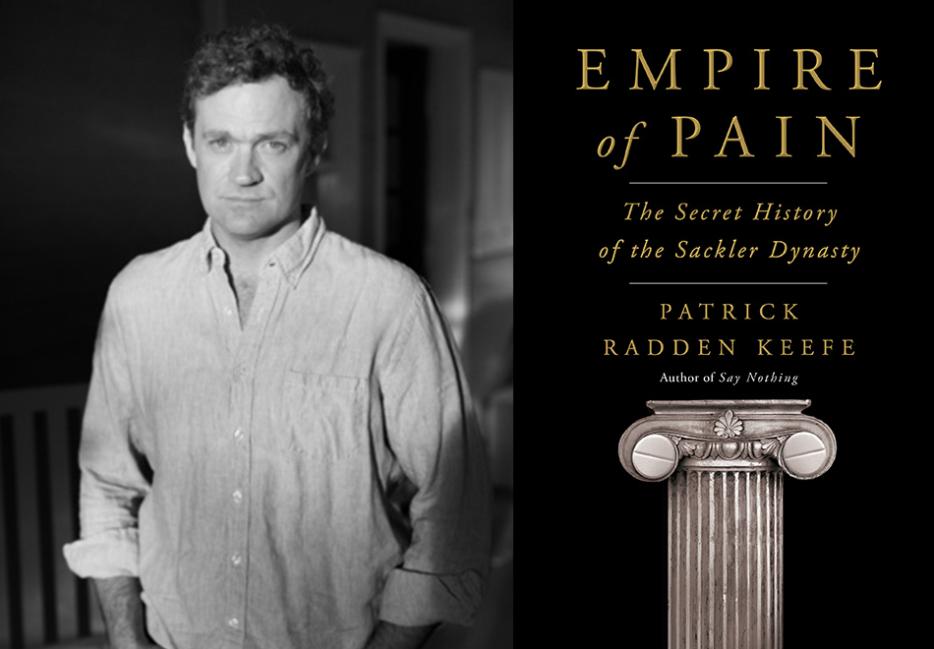

There is a harrowing scene midway through Empire of Pain (Bond Street Books), every sentence slick with danger and dread. It is an April morning in 1995. Inexperienced workers at a New Jersey chemical plant have been tasked with mixing volatile chemicals they scarcely know or understand. And on this particular day, the mix goes terribly wrong. “The chemicals were smouldering and bubbling, like the contents of some infernal cauldron, and emitting this sickening, noxious smell,” the journalist Patrick Radden Keefe writes. Temperature and pressure begin to climb. A chemist later compares the brew to a hydrogen bomb. Soon, the smell is so overwhelming, so odious, that it becomes clear something must be done. Seven men go back into the plant to try to clean the mess up.

Radden Keefe’s description of the chaos is so visceral that I was immediately reminded of a particularly distressing moment in HBO’s Chernobyl, when members of the cleanup crew race to shovel radioactive debris off the ruined reactor’s roof. Inside the New Jersey chemical plant, a similar threat is unfolding: urgent, palpable, and invisible to the untrained eye. As the men inside the plant begin to empty the smouldering vat, the mixture begins to hiss. Then it explodes. Five people died, forty people were injured, and incredibly, the owners of the facility felt no responsibility at all. As Radden Keefe recounts repeatedly over hundreds of meticulously researched and detailed pages, for the Sackler family this is something of a theme.

Empire of Pain is a book about dynasties and legacies, about cycles repeated across time and lineage, and the lengths that powerful people will go to hold onto their power. It is a story about a name, and how for decades, the Sackler name adorned countless museums and schools across the world while obscuring the source of their immense philanthropic wealth. It is a story about OxyContin, the powerful opioid created, marketed, aggressively sold and defended by the Sacklers, and the opioid crisis they helped create and sustain.

It is a story about a family more concerned with status and standing—with how they should be perceived, be remembered—than the impact of the drugs from which they made their fortune. It is a story shrouded in secrecy and obfuscation, one that starts with Arthur Sackler, born in 1913.

Radden Keefe has made a career out of finding the messy truths at the heart of sprawling mysteries, of pulling the most thrilling, revealing threads. Empire of Pain is based on a story he first wrote for The New Yorker. Last year he hosted an eight-part podcast that asks: what if the CIA wrote the Scorpion’s hit metal power ballad “Wind of Change”? Denial is a frequent theme, and the stakes are often high; Say Nothing, his last book, was about the Troubles and the IRA. His writing is vivid, gripping, and hard to put down; he knows how to tell a compelling story, how to put us inside people’s heads. That skill is of particular importance in Empire of Pain—a book whose main subjects were not merely reluctant but unwilling to speak with the author. Thankfully, Radden Keefe does not share the Sacklers’ penchant for silence, and spoke with me via phone late last month.

Matthew Braga: I saw on Twitter that you had come down with COVID. How are you feeling?

Patrick Radden Keefe: I'm fine. I'm better. Thank you. I was sick last week, right around the time the book was published. So I've been kind of isolating. I'm sitting in my backyard right now, away from my family. But my symptoms are not bad at all, and I'm actually out of isolation tomorrow. So I'm fine, thank you.

Say Nothing came out in 2019. Wind of Change came out in 2020. Now you have Empire of Pain. It's an incredible amount of output, and as someone who frequently feels like I'm not being productive enough, or writing enough, or publishing enough, I wonder if I could ask you: how?

It's been a busy few years, definitely. But it's a little bit misleading, because Say Nothing took me four years, during which time I didn't take leave from the New Yorker. So I was working on this book on the side, but I basically had a full-time day job. And then when that came out, I decided to write the Sackler book and do Wind of Change pretty close in time. At that point, I realized I couldn't stay at the New Yorker. I had to take a leave.

I like having different projects so that if I hit a dead end in one, rather than just kind of mope around and feel sorry for myself, I can turn my energies to another one. So it was really helpful for me to have the podcast going while I was working on this book, particularly because the podcast is just so fun and collaborative, and the stakes felt lower.

Are you saying that you don't ever still mope around and feel sorry for yourself?

Oh I do [laughs]. Believe me, I've been feeling very sorry for myself for the last week with my extremely mild case of COVID. But I think the pandemic affected different people differently. And for me, what it did was it just kind of wiped the slate clean in terms of plans. And that ended up being an opportunity. I had not a lot going on, I couldn't leave my house, and by an excellent coincidence of timing, I had done a lot of the research already. So really all there was left to do was just write the damn book.

Secrecy figures prominently in Empire of Pain, and also in Say Nothing, Wind of Change, and the work that you've done previously—secrecy in terms of worlds and occupations, but also secrecy as a human trait. What it is about secrecy that fascinates you? Why is that a well you keep returning to?

I don't really have a good answer for it. It's funny, because in my writing, I am always looking for these rosebud moments in the lives of characters that help explain who they are. And I stumbled on that moment when Isaac Sackler tells his son [Arthur] the importance of a good name. He knows it's the most important thing. That becomes this key that helps me understand them. But I'm not as good at identifying those moments in my own life.

Some of it is probably a stubbornness on my part where, if there's something I'm not supposed to know, I want to know what it is. But I'm also interested in the dynamics of secrecy in a community, in a family, and even on a national level. I'm interested in the stories that people tell themselves about the choices they've made. I want to know the story they tell themselves when they look in the mirror. You can also ask those kinds of questions about a nation looking at its own history and how it accounts for choices that have been made at a national level.

You mentioned that rosebud moment of Isaac Sackler conferring the value of a good name. I was so struck by how good of a frame that was to look at the family through. It’s so simple, but so powerful in its simplicity. When do organizing principles, or threads like that, typically emerge in the process? Was that something that you had very early on? Or was that an “ah-ha!” moment later on, like you had with Say Nothing?

It was fairly early on in my research. I don't really have a technique per se, other than to just do as much reporting as possible, and to report as widely and as deeply as I can. And I know those details when I see them. It's my favourite thing, honestly, certainly professionally and possibly in life—that moment when you're in the midst of reporting and then there's just this thunderclap moment when you discover something. And in that case, I knew that Arthur Sackler had donated money to have this library with the Sackler name at Tufts University in the 1980s. Arthur didn't give all that many interviews in his life, and I thought I had them all. But it turned out that there was this newspaper at Tufts that had done a special issue in which they covered the opening of this Sackler building. Arthur gave a one-page interview—this is, like, something on microfilm, and I think I got somebody to PDF it and send it to me—and in that interview Arthur tells this story about his father. And as I was reading it, I knew, “This is it. You have to tell the story early in the book.” Because it explains this kind of bizarre family attribute that you then see manifested over three generations.

That idea of a name and the legacy it can confer, the values that it can confer upon the wearer… once you started thinking about that as a frame, did you start to look at your own world differently? Your own family differently? Your friends?

Oh, that’s so interesting. I don't know that I did. I have an extremely common name, so I don't know that I ever had any sort of particular sense of a name as quite the talismanic thing that it was for the Sacklers. What I became very aware of after discovering that story about Isaac is you start seeing this theme played out with different Sacklers. They talked about it in this way that just seems very weird. I’ve never known anybody to discuss carrying a name in quite that way. There's an analogy that I didn't really think about much when I was writing the book, but which a number of people have raised since the book has come out, which is Donald Trump, and that idea of the name as brand.

On the other hand, it wasn't far into the book before the dysfunction of the family in HBO’s Succession popped into my brain, and I'm glad to see it was mentioned in the book as well. Do you have the sense that the world of Succession is even on any of their radars?

One thing that I puzzled over in this book with the younger generation of Sacklers was how anybody could be so un-self-aware. I imagine they would watch something like Succession and think that it couldn't possibly have any comparison to them, because they're all very serious people who are really brilliant and bear no resemblance whatsoever to the pampered idiots in that show. The funny thing for me was three sources, totally independently, compared the experience of working for the family and the company to living inside that show.

Denial has always been a subject I've been very interested in. And part of what's so intriguing to me about the Sacklers, as personalities, is that they believe that I'm wrong, and that The New York Times is wrong, and The Wall Street Journal is wrong, and The Washington Post is wrong. And the 49 states that are suing their company are wrong, and the congressional investigators are wrong. And all the books are wrong. And all the studies are wrong—that they're just terribly misunderstood.

By the end of the book I was left with a feeling of, well, if everything up until this point hasn't spurred some introspection—if even the arrival of this book doesn't spur introspection—then what will?

I think that's exactly right. In recent years there's been a very slight recasting of their public persona, their kind of public posture on this issue, where they're saying, “Oh, we feel great compassion. We care about the opioid crisis. It is very regrettable that there has been a loss of life associated with our product”—all this kind of carefully scripted stuff. And what I found so revealing is I got these private emails from just a few years ago—like 2019, 2018, where privately, Jacqueline Sackler is saying, “our family’s done nothing wrong,” and Mortimer Sackler Jr. is saying, “the so-called opioid crisis.” Their willingness to cynically recast the talking points, just to the degree that they think is necessary—which is to say, like, “We accept no responsibility, we make no apologies. But opioid crisis, sad”—inclines me to think that nobody's going to be having any moral epiphanies anytime soon. I just don't think they're capable of it.

You combed through so many documents for this book. The Sacklers also wouldn't speak to you, wouldn't answer your questions. What was different this time, compared to some of the work you've done in the past, in trying to peel back those layers of secrecy?

It actually wasn’t that different. The idea of a big, formidable reporting project in which there's a story that I want to tell that a variety of people who are characters in the story would prefer that I not tell—that actually is pretty familiar territory for me. One big thing that was different in this case was… I often think about Robert Caro, who published a book about reporting and writing while I was working on this project. And he has a line in that book, where the advice that he gets as a young reporter from some seasoned old newspaper man is, “turn every goddamn page.” And it was funny, because I thought about Caro turning the LBJ archive. Like, there’s millions of pages! It’s a daunting prospect. And I was in a similar situation with this where, usually, the problem is you want, as the lawyers call them, the hot docs. You want the hot docs. You want to get your hands on the hot docs, and there's never enough that you can get your hands on. In this case, there were too many. It was overwhelming the amount of paper, and it led to some really crazy, truly crazy moments in terms of reporting.

How so?

At the risk of exposing what an obsessive maniac I am… at a certain point fairly late in the game, I was close to done with the book, and a source that I knew—a lawyer, who had been involved with some litigation involving Purdue—called me up and said, “I have 40 boxes of documents that I want to share with you. I'm going to send them to your house.” And I got very excited at the prospect of 40 boxes of documents. But the Sacklers had sent me what's called a litigation hold, which means that a lawyer representing the family basically said, “Look, we're probably going to sue you. So don't destroy any of your files, any of your emails, any of your text messages, any of that. You need to hold on to everything until the day that we sue.”

I had this conversation with my wife and I said, “This guy is gonna send 40 boxes of documents to the house, and we can never throw them away.” And she was just like, “No, we cannot have 40 boxes of documents that we just carry around with us indefinitely into the future. That's not an option.”

So I decided to go fly to the place where this guy was—that way I could just go through the documents and they wouldn't be in my possession—find what I needed, and then come back. This is during the height of the pandemic. I spent four days going through these 40 boxes of documents. And in the end, I didn't use a single thing from any of them. But I also couldn't not go through them, you know what I mean? Like if I hadn't done it, I'd still be wondering now if there was some amazing little golden nugget that I overlooked. The only way to figure that out is just through brute force. It’s through turning every goddamn page.

We're talking about stuff that is very heavy on research, very heavy on time. In this particular case, you have legal threats from the Sacklers coming at you as well. I've been thinking a lot about how folks are leaving jobs and going independent and starting newsletters and going direct to their readers. I know you've been a freelancer, and you also know how difficult it is to be a freelancer, and I wonder, would you be able to do the kind of work that you are doing today without the support of your editors? The backing that you have of the institutions that you work for?

Yeah, not at all. Personally, I'm so grateful for my editors, that I think I'd be very nervous about doing anything where I didn't have a really astute editor coming in after me to protect me from myself. I feel incredibly lucky to write for The New Yorker—both in the sense of, the people that I'm working with are so resourceful and so smart and make everything I do so much better. But also because there's just a level of institutional support, that in the case of the initial Sackler piece, yeah, it would have been very hard to do that without my boss David [Remnick], my editor Daniel Zalewski, and our general counsel at The New Yorker, and all the fact checkers, and everybody willing to stand by this piece of writing that made some very powerful people very angry. And similarly with Doubleday, they've been incredibly supportive since the beginning. I think the Sacklers probably won't sue. But if they did, I'm confident that Doubleday would be amazingly supportive through that process as well. So I don't take for granted for a second the kind of structural institutional advantages that allow me to do this work. None of this is easy. And I'm not alone. I have very good supportive people and resourceful people in my corner.

In the book you detail the level of obfuscation the Sacklers go through—certainly Arthur Sackler—to obscure their various business ventures, the connections between those ventures, the conflicts of interests, the subterfuge. Would that be harder to pull off today?

I think it would be harder. Yeah. It would be a lot harder. I went through the files of the Kefauver investigation [into pharmaceutical industry practices in the early 1960s], and I was just kind of amazed that, in some of their internal reports, you have these senate investigators from this pretty powerful committee. And they just had some very baseline questions, where they were just saying, “Who are these brothers? What's the scope of the stuff that they control?” And I think that today, when you think about accessing corporate registries and looking up identities that are associated with particular addresses and so forth, there would be a level of easy checkability that would probably make it hard to obscure things to the extent that they did. That doesn't mean to say that they wouldn't still be able to keep things pretty obscure. I mean, Arthur Sackler had all these weird relationships where he would put frontpeople in instead of himself, and he had all these handshake deals, and that kind of stuff is not, I don't think, any more legible today with the Internet and various databases for reporting than it would have been back then. But I think in terms of the kind of baseline questions, like, “Who’s this family? Where do they live? Which businesses do they control? Here's this strange building on 62nd Street; how many corporations are registered there?” Those types of questions I think would be easier for reporters to answer today. And congressional investigators.

In a similar vein, I wonder whether the ability to burnish your legacy in the same way would be harder today? Would it be harder to build a legacy like that If you were starting today? If you had started in the ’90s, let's say, or the early ’00s?

I don't know. What strikes me as significant, though, is that with the Sacklers, it was kind of an open secret. When I reported on the Sacklers in 2017, I was not the first person to report that they were the owners of Purdue Pharma, this company which had pled guilty to felony charges and had been so intrinsic in helping start the opioid crisis. The truth was out there for anybody who wanted to Google. And that was true in 2003, when Barry Meier's book came out. It was true in 2015 when Sam Quinones’ book came out. But even then, at a time when you had the Internet and stories, if people cared to look, connecting the family to the opioid crisis, they kind of managed to sort of stay above the fray. They had no problems at any of the institutions. After my piece came out in 2017, The New York Times contacted 21 cultural institutions, and there wasn't a single one that put any distance between themselves and the Sacklers. So I don't know that it's gotten that much harder.

Honestly, what really started bringing about some accountability in the philanthropic sector for the Sacklers was Nan Goldin more than anything else. And Nan Goldin is kind of lightning in a bottle. The idea that you would have somebody happen along who was a revered artist whose work really meant something in that world, who was recovering herself from an OxyContin addiction, and who, because of her experience during the AIDS crisis, had this history and taste for and talent for activism… it's hard to dream up a more threatening scenario for the Sacklers than Nan Goldin.

Do you think the names would have come down if not for her?

I don’t. I think my piece had an influence. And there was an Esquire piece that came out at the same time. And I think that made a difference. And I think that when the state of Massachusetts became the first state to individually sue members of the Sackler family, that made a difference. But I also think that it was Nan's willingness to be the skunk at the garden party and actually show up at the Guggenheim and show up at the Met and show up at the Louvre.

And has that had a knock-on effect? I remember around the same time I started to see other artists say, “Okay, well now we have to do the same for exhibitions and galleries that are funded by oil and gas money,” for example. Has that ripple effect played out?

This is the big fear of the institutions. And I actually think this is part of the reason the institutions have, in many cases, been reluctant to take any bold steps when it comes to the Sacklers. They're worried that if you start introducing an ethical litmus test to any money given to arts organizations the arts might dry up altogether. And I think you have started to see hard questions being asked. To what degree are these types of institutions complicit in reputation laundering? To what degree do they end up effectively co-signing on some of the really repulsive behavior of the families and businesses that donate to them? I don't, for a second, pretend that these are simple issues. But I also feel as though we are living through a moment in our culture in which this question of naming and legacies and the kind of prerogatives and institutional approval that money can buy, are being re-evaluated almost in real time.

For all the people affected by this crisis, people who have lost loved ones to opioids who have struggled with addiction, what do you hope this book will mean to them?

After my piece in The New Yorker came out in 2017, I started getting a lot of mail from people who had lost loved ones, or who had struggled themselves with OxyContin or other opioids. I got more mail about that piece than I've ever gotten about anything I've ever written. And there was a pretty consistent strain in a lot of these notes where people were just saying, “Thank you for helping me understand the forces that my loved one was up against.” With Purdue and OxyContin, there's this whole notion of the drug abusers—as Richard Sackler called them, the reckless criminals, the scum of the earth. And I think that's a powerful idea, the idea that it's really entirely about the kind of personal moral character and choices of individual consumers. And I also think that's bullshit. I think that in the case of OxyContin, you see lots and lots of people who had ready access to the drug recreationally because it was flooding their communities, or who were prescribed the drug in a doctor's care and found that there was a sort of undertow, that they just couldn't control themselves and their relationship to that drug. And if I can tell a story about the huge juggernaut that those people were up against—between the pharmaceutical company and all the pharmaceutical reps, and the deceptive marketing, and the FDA being asleep at the switch, and the Department of Justice not doing its job to hold the company accountable in 2007, and on and on and on—that when you array all of that systemic corruption, I think there are some individuals who just don't stand a chance. And if that can bring some comfort to people, that would mean a lot to me.