“We had a bit of excitement,” says Jeff VanderMeer as I log in to our Zoom call. “An immature hawk just landed on the bird feeder,” he explains, lifting his digital camera towards the computer screen to show me. VanderMeer speculates that the young hawk was learning to hunt, but had yet to absorb the finer points of stealth.

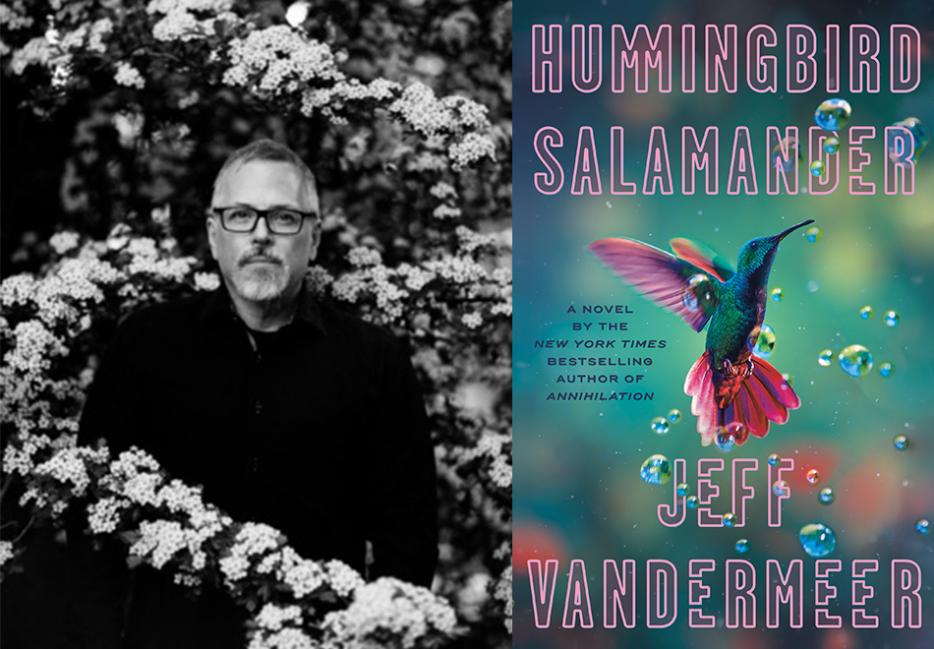

Animal behavior is one of the lenses through which VanderMeer, the prolific, Florida-based “weird fiction” author explores the familiar, yet more confounding, behavior of humans. VanderMeer is best known for his Southern Reach trilogy, which includes the novel Annihilation, adapted into a 2018 film by Alex Garland and starring Natalie Portman. He has published more than a dozen other novels and books, including anthologies of science fiction edited in collaboration with his wife, the renowned publisher and editor, Ann VanderMeer.

His new eco-thriller, Hummingbird Salamander (McClelland & Stewart), follows a middle-aged tech executive, wife, and mother—dubiously named “Jane Smith”—as she descends into a risky mission instigated by the mysterious activist (and possible bioterrorist), Silvina. A near-extinct hummingbird triggers a cascade of events that may very well bring Jane’s (and possibly the) world to an end.

What seems like a corruption of Jane’s normal life quickly becomes an awakening, a frequent theme in VanderMeer’s work, which often deals with speculative, uncanny manifestations of the climate crisis and environmental destruction. As in Annihilation, sickness has a clarifying effect in Hummingbird Salamander; fever that burns clean as it burns down.

On a day when a young hawk attempted to blend in with VanderMeer’s backyard birds, we spoke about surveillance and paranoia, writing about/through a pandemic, love as a possible human flaw, animals begging to be exploited, and secret autobiography. When I apologize for going over our allotted interview time, VanderMeer gamely says he has nothing much to do today. “Well,” he pivots, “I do have to go outside and feed the birds.”

Naomi Skwarna: The novel features so many massive and high-stakes topics—wildlife trafficking, eco-terrorism, climate change, security and surveillance. How did you come to connect these different subjects through the mystery of Silvina?

Jeff VanderMeer: I had this idea of a character saying, “assume I’m dead when you read this,” and an image of a hand holding a taxidermied hummingbird. Everything came out of that. We’re living in an accelerated capitalist system that depends on things like surveillance. The window of what’s acceptable for activism has shrunk. I wanted to comment on the fact that the way we talk about the environment and activism has changed because activists are seen as the enemy by governments. They just passed a law in Florida with regard to Black Lives Matter that now means that peaceful protests may result in ten years in prison.

Early in the novel, there are several allusions to a coming pandemic and then later on, references to a surge of pandemics. You never name COVID or even place the story in a particular year, but I wondered how the global pandemic affected your realization of the book?

I was actually writing and rewriting up through the pandemic, and keeping in mind that there was a lot of election stress that was already leaking in without the pandemic. All of that created a sense of claustrophobia and paranoia that I was trying to channel. [This] pandemic is definitely in there emotionally, but I was also wary of being too specific, because everyone has their own experience of what the pandemic is. I wanted to allow the reader to bring their own experience of it to the novel. We’re all still making sense of it, so that felt like a mistake to be too specific, but it also felt wrong for it not to be in there.

It going unnamed fits with the way Jane draws certain characters in broad strokes for anonymity. There’s something very pointed about keeping the pandemic anonymous.

Oh yeah, definitely. I do this a lot. In Annihilation the characters’ names are never given, and in Borne it’s like the city itself is the anonymous part, with the characters being in sharp relief. I find the idea of a certain distance very useful.

And yes, the things that are named more precisely, it does make them stand out, like you said. Related to the idea of contagions—I thought it was interesting that Jane, as she’s drawn deeper into Silvina’s mission—refers to what’s happening to her as an illness, and the hummingbird is a “terrible catalyst” for that illness. I’d love to know how you picked the hummingbird and salamander as these catalysts?

At one point I was thinking that there would be more pieces of taxidermy, but that began to feel like some kind of weird scavenger hunt. I narrowed it down to just the hummingbird and the salamander specifically because the hummingbird has a long migration that covers thousands of miles. It’s very indicative of a certain thing about the climate crisis for us too, which is that the hazards of that journey are much worse with so much human development, and changes in temperature and climate; and then the salamander because it breathes through its skin and is extremely vulnerable to environmental pollution. It’s also fairly stationary, so they felt like opposites in a sense.

Neither of the species in the novel is extinct. I didn’t want to use an animal that was totally extinct in reality because part of the hope of the novel is the fact that there are real hummingbirds and salamanders still out there, and their situation is our situation, whether we realize it or not, in terms of if we’re going to weather this crisis.

I asked a friend of mine, the biologist Dr. Meghan Brown, to create the hummingbird and the salamander, their whole life cycles, so I could react to that. It really was quite interesting to take someone else’s work and incorporate it into the novel.

How did the two of you determine what the hummingbird and salamander would be like?

I needed a hummingbird that migrates from the Pacific Northwest down to Argentina, and the salamander also had to be from the Northwest, with a larger mythical version of it. That was based on having read a lot of stuff about Bigfoot legends, but around giant salamanders in Northern California. I didn’t expect that I would use too much of [Dr. Meghan Brown’s] writing, but it was so beautiful. Especially with the hummingbird, Jane gets hooked on the mystery in part because of learning about it, and thinking about the hummingbird being special to Silvina.

[Mumbling foolishly] I think they’re sometimes called, like, flying gems or flying jewels? They’re so small and delicately beautiful. Finding that hummingbird would feel like finding a profound treasure.

Absolutely, that’s also the thing—the contrast between them. There are some quite brilliant-looking salamanders, but that’s not really what you think of. I think we relate more to hummingbirds because we encounter them more often, and because they have very sharp personalities. They’re always checking you out! Here in the garden in Florida, they’re always periscoping up to the walkway and kind of scanning me before zipping away. The salamander has more of a primal or prehistoric quality.

On the subject of relating to animals—you quote at length a non-fiction book from 1938 called Oddly Enough: From Animal Land to Furtown. I couldn’t believe it was real! The passages you quote are truly deranged.

It’s actually over my shoulder right here. [Holds book up to his screen] It has these weird illustrations of animals, all of them happy to be turned into fur, wearing tuxedos. It’s really a very creepy book.

It made me think of advertising that features animals who want to be eaten. They’re basically winking and beckoning you towards them, begging to be devoured.

It seems like an outlier when you first read it, and then you realize that this propaganda still exists in the world, where we try to get animals to tell us that they’re okay with us exploiting them. I found this book in a used bookstore in Minneapolis, about ten to fifteen years ago, and in some ways I didn’t want it in the house, but in another way, I was like, I know that I’m going to use this in something because it’s already suggesting fiction. It is fiction in its way.

The reclamation of nature is thematic in a lot of your writing, and here, it comes with the possibility of eco- and bioterrorism. Jane is initiated into Silvina’s cause, while simultaneously learning the truth of her family’s history, which in her case is touched significantly by poverty, mental illness, abuse, and dementia. I was curious to know how you would like a reader to think about the way these particularly human issues fit into the grander narrative of humans exploiting our environments and natural resources.

I don’t know that they do. Here, I think it impacts how Jane responds to the initial message from Silvina, more than it has to do with the foreground of the novel. I do think that there’s something useful in the contrast between Jane having grown up on a farm, with that background, and the fact that she’s a security analyst within a high-powered, high-tech world. The main thing for me is that I have to follow the individual character’s quirks as I see them. There’s also stuff in there—like, I once received letters from my first real writing instructor—she was absolutely amazing—but she wound up in a situation without enough care where she had the same kind of symptoms as Jane’s mother. I would get letters from her where I was a character, like she had re-imagined me as somebody else. It was deeply horrifying and moving, and I had all these emotions about it because she’d been so important to me as a writing instructor.

Another thing that was fairly unique about that relationship is that she was more-or-less giving me creative writing instructions on the side, because she was in a different department. The university I was at had a very misogynistic creative writing department that I wanted no part of. I could see the damage coming out of it on some of the other students, and they’d tell me about it. So there was also this aspect of getting tutorials from someone who didn’t need to be giving me that. It was a very precious gift.

Sometimes there are things like that, which you’re trying to work out the meaning of, so you put it in a different context. I’ll probably write a personal essay about that whole situation someday, but for now, a lot of autobiography in different fragments and contexts often gets into my fiction. People don’t much remark on it because it’s kind of a secret autobiography; it’s not really something that you would know automatically has some connection to me. But it feels important to the underpinnings of certain characters.

On the subject of his early writing, and borrowing wisdom from the movies:

When I was a very young writer, and fairly arrogant, I didn’t realize that you need to leave some imaginative space—like I said about wanting the reader’s experience of the pandemic to come, but not forcing it on them. When you’re just starting out, of course, you’re kind of a control freak, but you don’t necessarily have control over your technique. Another thing that I didn’t realize until later—and I learned this from Karen Joy Fowler—she’ll write the scene, and then she’ll leave it out. She realized that the echo of it is still somehow in the book; the ghost of it’s still there.

That seems very cinematic to me.

I am a big fan in general of stealing things from cinema and acting classes, in terms of creation of character.

Oh, can you give me an example of some technique you stole?

For this novel, just trying to imagine the physicality of the character [of Jane]. She’s a really big person, you know, she takes up space and, in some ways, she enjoys that. So I had to think: how does someone like that move through the world? They don’t think about certain things after a while, but maybe they’re reminded every once in a while of that physicality. Little things like that.

Jane is a vulnerability analyst and part of her work involves “anticipating flaws in the human element.” Then she leaves that world and ends up as a sort of detective and vigilante. I wondered, where do love and intimacy fit into Jane’s characterization? And in the case of this novel, would they be considered flaws in the human element?

I do often write about loners and people who are just fine not having that much connection. I think to some degree, the biologist in Annihilation is a little like that. But I think part of this novel is Jane looking back and trying to make sense of all this. Whether Jane thinks she’s protecting [her family], I don’t think at the end of the day she’s able to make sense of whether she’s done the right thing there. Or whether she has an impulse to both protect them and distance herself from them. The short answer is that she is, in a way, trying to jumpstart her life, out of a situation that for a lot of us would be the ideal, but that for her is not the right fit. Deep in her psyche, she knows something is wrong in the life she has. And that’s also probably why she’s somewhat reckless at conventions, why she’s reckless about pursuing this thing.

I personally know some people who look like they wrecked their entire lives from the outside, only to reform them later in a way that makes sense to them. And the reason that they wrecked their lives is because they recognized that eventually, it was going to kill them inside in some way.

I have a final question for you. I read that you once worked with a group to band saw-whet owls, and I just want to ask if you personally held one.

I did hold one, and I couldn’t believe how incredibly tiny it was. It’s really the tiniest bird. We have a barred owl down in the yard.

You have an owl in your yard?

Yes! This house hugs a little ravine, and the upper level is way up in the canopy because of the slope. So we have this hilarious thing where I’ll turn the corner on the walkway, and there’ll be a barred owl in a tree, like 20 feet away at eye level. I’m surprised, but the owl’s really surprised.

Owls are very good at looking surprised.