For nearly eleven days in mid-March, Vladimir Putin was missing. His meetings were cancelled, he disappeared from the public eye, and the Kremlin refused to explain what was going on. Speculation spun out of control: was his mistress giving birth to a secret child? Had he had a stroke? Or plastic surgery? Was it a coup?

Ukrainians, at war with Russian-backed separatists in the east of their country, were particularly excited by the latter possibility. Andrii Kapranov, who works in web marketing in Kiev, lost no time in creating a website to track the Russian leader’s disappearance. On the site, big, bold numbers counted, in real time, the days, hours, minutes, and seconds since Putin had last been seen. In the background, the site played a looped video from the ballet Swan Lake.

Why Swan Lake? It may seem like a random artistic choice, but to anyone who lived in the former USSR, it made perfect sense. For many Russians, the opening strains of Tchaikovsky’s score are as likely to remind them of political upheaval as they are the beauty of classical ballet. When Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982, after nearly two decades in power, state-controlled television stations cut into programming not with news of his death or an announcement of who would next lead the country, but with broadcasts of Swan Lake “in its full-length, four-act, three hour expanse,” writes Stanford dance historian Janice Ross in her new book , Like a Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia. The broadcasts were a stalling tactic, meant to block access to the news while the Soviet leadership settled on a succession plan. The same happened following the deaths of Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko.

Swan Lake was so often the backdrop for Soviet political upheaval that seeing it on television became a tip-off that all was not well in Moscow. In August 1991, Ross writes, when a group of communist hard-liners attempted to overthrow Mikhail Gorbachev’s government, television programs again were interrupted; for days, the only thing on state TV was a continuous loop of Swan Lake. Sergei Filatov, a member of the Russian legislature, was on vacation at the time. “I turned on the TV and saw the swans dancing,” Filatov told the Moscow Times. “For five minutes, ten, for an hour. Then I realized that something had happened.” He immediately got on a flight to Moscow, where he played an important role defending the city against the attempted takeover. (One of the leaders of the coup, Vasily Starodubtsev, later admitted that the broadcast was a strategic error.)

*

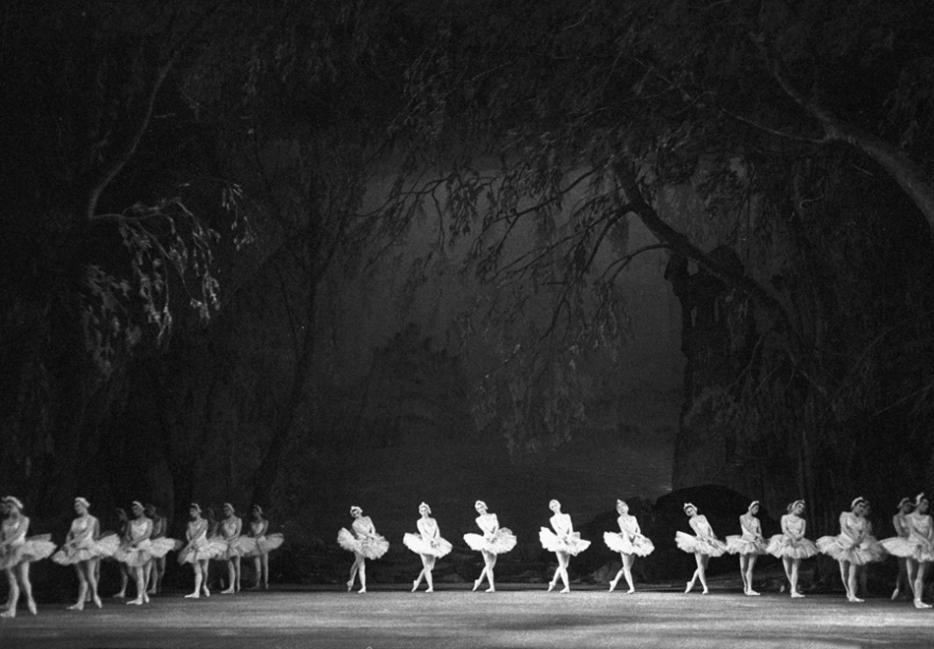

The Soviet-era television broadcasts the website referenced are only one chapter in the strangely entwined history of Swan Lake and Russian politics. Beginning in the 1920s, Soviet government policy shaped both the form of the ballet itself and its audience. When Swan Lake premiered in Moscow in 1877, it was not considered a great success. The story is a dark one, even by the fantastical standards of classical ballet. It centres on a young prince, Siegfried, and a woman, Odette, who has been turned into a swan and held captive by a dragon-like winged sorcerer. The only way she can escape is if a man falls in love with her and promises to remain faithful to her. Siegfried, of course, falls in love. The sorcerer sees a threat. So he tricks Siegfried into declaring his love for another woman, a black swan who resembles Odette but is in fact her opposite. When Siegfried and Odette realize what he has done, they commit suicide together; their only chance for happiness is in the afterlife. The ballet is set to a Tchaikovsky score as harrowing as it is beautiful, with suggestions of tragedy underneath even its joyful moments. Despite the fact that the original version was re-choreographed in the late 1890s, Swan Lake was not, in its first decades, the sensation that it would later become.

But after the 1917 revolution, the whole of Russian ballet faced something of an existential threat. “The opera and ballet theatre were constantly accused of being irrelevant in revolutionary society,” said Christina Ezrahi, a scholar of Soviet-era dance. The government wanted to “sweep the slate clean of everything that went back to the aristocracy,” Ross added. (It’s possible that ballet got a pass in the end because Lenin understood the potential it had to transmit information to the largely illiterate Russian masses.) Behind the scenes, directors, choreographers, and critics who were interested in protecting the art form began to wonder how highbrow, opulent classical ballet might be made to fit in with the post-revolution mentality.

Increasingly, that mentality valued socialist-realism, the state-sanctioned theory that art should present a positive view of the communist struggle, and of its future. Much of the classical repertory was slowly tweaked to bring it in line with socialist-realist principles. Giselle, for instance, a Romantic ballet about a young girl who dies of a broken heart after discovering that her beloved, Albrecht, is engaged to someone else, was rewritten into a parable about the evils of class distinction. Emphasis was placed not on the disagreement between the lovers, but on the fact that Albrecht was a thoughtless nobleman who trifled with Giselle, a peasant, causing her anguished death.

Of all the classical ballets, Swan Lake received the most blunt treatment. In the early 1920s, the Bolshoi, one of the two major Russian ballet companies, mounted a production that recast the tragic tale as a battle between good and evil, clearly illustrated by the black and white swans. In order for the metaphor to carry through, though, the story could not end with the lovers’ deaths. “A new, happy end showed the victory of good over evil which, of course, fit very nicely into the combative ideology of the new regime, which was constantly talking about an all-or-nothing, black-and-white struggle between communism and capitalism,” Ezrahi said. This is how the final sixty seconds of Swan Lake, set to perhaps the most heartbreaking and dramatic music in all of classical ballet, came to depict Siegfried vanquishing the sorcerer and living happily ever after with Odette, rather than plunging headfirst into a lake.

Nikita Khrushchev saw the ballet so often that he told the Bolshoi dancer Maya Plisetskaya it had begun to make him ill. “He once complained to me, toward the end of his reign, ‘If I think about having to see Swan Lake in the evening, I start to get sick to my stomach,'” Plisetskaya wrote in her memoir. “The ballet is marvellous,” Khrushchev had continued, “but how much can a person take?”

The other big Russian company—originally called the Mariinsky, but renamed the Kirov Ballet, after a Bolshevik leader—held off on modifying its production of Swan Lake at first. But eventually, it, too, felt pressure to do away with the tragic ending. Beginning in the mid-’30s, as Josef Stalin exerted more and more control over Soviet cultural production, there was increasing scrutiny of ballet by the communist party leadership. “There were layers and layers of review,” Ross said, not only of a work’s libretto, but of every aspect of the staging and production. Government officials would not hesitate to suppress a work if it was deemed insufficiently nationalist and patriotic, or otherwise unacceptable. There were very real risks of repression and punishment for those who did not fall into the party line. So the next time the Kirov mounted a production of Swan Lake, in 1945, the ballet was re-choreographed. The company had previously presented the story as a psychological investigation of Siegfried’s descent into madness. That was done away with in favour of a happily-ever-after ending, which is still performed today.

The Bolshoi and Kirov’s sunny retellings of the ballet are the ones that turned the work into a resounding, state-sanctioned success. Ross notes that in Russia, ballet had longstanding links to the military, and the Soviet-era Swan Lake can be understood as part of that tradition. Onstage, row upon row of identical white swans beat their arms in sync, presenting the picture of a “disciplined, uniform citizenry” that the government wished to show to the world. In the decades that followed, Swan Lake, more than any other ballet, became emblematic of Russian dance and of the Soviet state. Stalin saw the production dozens of times, and both he and his successors ensured that a performance of Swan Lake became mandatory entertainment for any visiting head of state. A 2007 article in Pravda claimed that Llewellyn E. Thompson, long-time United States ambassador, “saw the spectacle 132 times during seven years of his work in the USSR.” Nikita Khrushchev saw the ballet so often that he told the Bolshoi dancer Maya Plisetskaya, who was famous for her rendition of Odette, that it had begun to make him ill. “He once complained to me, toward the end of his reign, ‘If I think about having to see Swan Lake in the evening, I start to get sick to my stomach,'” Plisetskaya wrote in her memoir. “The ballet is marvellous,” Khrushchev had continued, “but how much can a person take?”

Any attempt by ballet companies to address such Swan Lake fatigue was quashed by the government. In 1969, the new director of the Bolshoi, Yuri Grigorovich, proposed doing away with the fairy-tale ending in favour of a much more ambiguous production with a tragic conclusion. The government wouldn’t have it, and the production was censored. Happily-ever-after Swan Lakes continued to be performed for another several years.

*

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the Bolshoi was finally able to stage Grigorovich’s ballet, and still performs a version of it. But Swan Lake’s history of political entanglement didn’t end when the USSR fell. Recently, the ballet has been taken up as a means of protesting Russia’s incursions into Ukrainian territory. In April 2014, shortly after Russia annexed Crimea, four dancers dressed as white swans walked through a display of tanks and weaponry onto a stage set up outside Odessa’s museum of military history. They were accompanied by a local politician, who gave a short speech before the dancers performed. "For millions of Soviet people, televised performance of the world-renowned ballet Swan Lake always signalled a change in the country's leadership,” he said. "Because Vladimir Putin has made a fatal mistake by unleashing aggression against Ukraine, today Odessa, as a cultural capital, performs for him this portentous composition.” And though Putin’s recent disappearance did not end the way that many Ukrainians had hoped—he re-emerged after a week and a half; he’d probably just had the flu—Kapranov, the creator of the website tracking the leader’s absence, has kept the site online. The numbers keep counting upward, though they have been reset to track the days, hours, minutes, and seconds that Putin has been in office. (At last count, 5706:15:54:50.) The swans continue to dance in the background, a never-ending loop.

It is telling that, while the Mariinsky Ballet got its old, pre-revolution name back when the Soviet Union broke up, it never gave up its Soviet-era Swan Lake. The company’s leadership, which has been outspoken in its support of Putin and his actions in Crimea, still chooses to perform the fairy-tale ending. Much of the production is beautiful, but the last act is hard to take seriously. From the moment, in act two, that Siegfried takes Odette’s hand, the ballet has been building toward tragedy; there is a sense in the low, anguished notes of the score that things can only go one way. Instead, as the final act draws to a close, Siegfried struggles briefly with the sorcerer and rips off one of his black, reptilian wings, sending him crashing to the floor. He writhes there comically for a moment, leaving just enough time for Siegfried to be united with Odette as the curtain falls. The pair’s smiling faces feel superficial, dishonest.

I asked Yuri Fateyev, the current director of the Mariinsky Ballet, why, in light of Swan Lake’s political history, his company does not go back to the original ending. “I think most everybody forgot about this,” he told me, in reference to the Soviet Union’s television broadcasts of Swan Lake in past times of turmoil. “You know, most of the Russian fairy tales finish with a happy end. The good guys kill the bad guys, and everybody’s happy. I think maybe this is what they tried to do with Swan Lake: they tried to make happiness for everybody, the audience too.” Though, as the ballet’s original creators knew and the Ukrainian protesters have learned, fairy-tale conclusions are not so common in real life. It is the darker endings that we recognize as closer to our own.