“Keep working, Little Bit, keep working!” shouts Delen Parsley. Little Bit, also known as Kristina Naplatarski, is in the ring with a championship boxer, and things aren’t looking good. It’s the second round of her quarterfinal bout in the New York Daily News Golden Gloves, and the eighteen-year-old featherweight from Greenpoint, Brooklyn, isn’t throwing enough punches. Though Kristina has been training as a boxer since she was thirteen, this is only her third amateur fight: until she reached the age of eligibility, seventeen, she wasn’t allowed to participate in adult amateur bouts. Her opponent, Amanda Isaac, on the other hand, is two weeks shy of her 28th birthday and has years of experience on the amateur circuit.

Kristina is 5’5” and generally boxes at 125 pounds. She was given her nickname the first time she walked into Gleason’s gym as a scrawny seventh-grader who had just been jumped at school. Teen girls don’t often take up boxing—it’s far more common for women to get into the sport in their twenties—but from her first session, Kristina knew she wanted to train seriously.

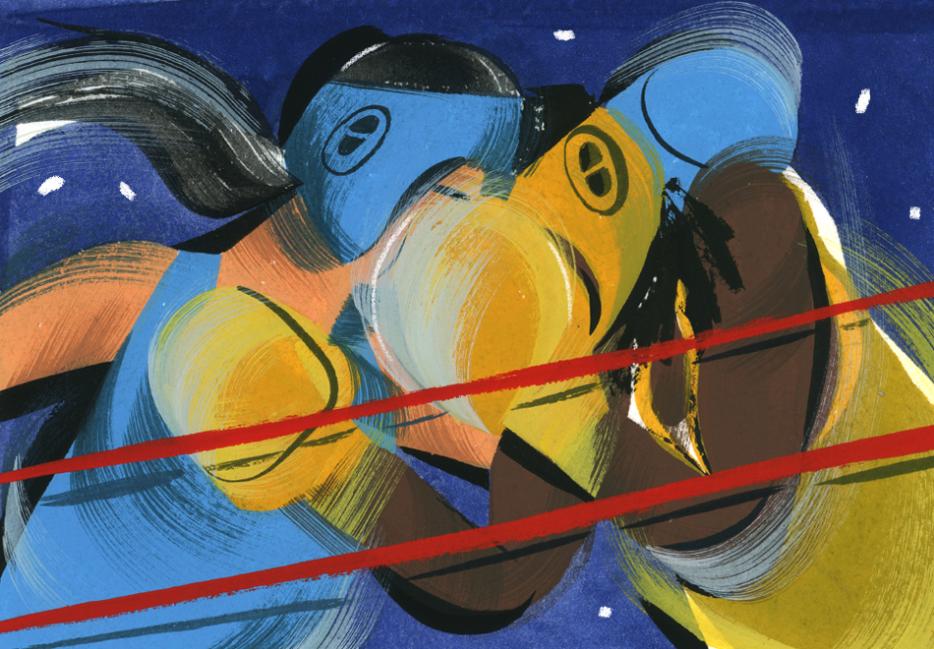

In the ring, in silky red shorts and a blue jersey, her stance is wide; she no longer looks little. Isaac throws a pitter-patter of punches: left hook, uppercut, left hook, cross. Jab, jab, Kristina responds, and Isaac jumps backward. “Back her up!” someone shouts from the bleachers. The day’s fights are happening at a Catholic boys’ school in Bay Ridge, and the gymnasium is full. The crowd murmurs softly; spectators eat hot dogs and chase babies as the boxers alternately step forward, feint, and jump back. The audience begins to whoop and yell only when one fighter or the other pounces, the volume rising with the intensity of the punches.

Kristina throws a cross, pauses, then a jab. “There you go!” yells James Thornwell, who, with Delen, is working Kristina’s corner. “Get her again!” But then Isaac lands a swift combination; a well-aimed hit knocks Kristina's head backward. The ref signals a standing eight count, meant to give an overwhelmed boxer a moment’s pause. She follows Kristina back toward her corner and lifts two fists in front of her face. One by one, she counts off thumb, pointer, middle finger, until she reaches eight. Then she waves the fighters back to the centre of the ring, yelling, “Box!”

How did an eighteen-year-old with only two fights under her belt wind up facing a former champion in the first round of a major boxing tournament? If Kristina and Amanda Isaac were men, it would never have happened. But women’s amateur fights are often mismatched, one of many dysfunctions that have plagued the sport since women were first allowed to fight competitively in the mid-‘90s. Two decades later, women’s participation in boxing remains low, from the professionals, where women are barely paid to enter the ring, down to the amateurs, where there are ongoing challenges recruiting women to compete. Low participation means that at the amateur level, the field is continually unbalanced: a few very experienced fighters dominate the sport, meeting the same opponents over and over, frequently with the same outcome. It seems that what the women’s amateurs do best is produce a long line of journeywomen: skilled boxers who nonetheless have little hope of winning their fights or advancing in the sport.

Kristina and Amanda Isaac move back toward the center of the ring. Kristina lands a low shot, jogs forward, then hits with a jab. But she continues to take more punches than she throws. A few moments later, the ref gives Kristina another standing eight. If she receives a third, the fight will be finished.

*

Several weeks earlier Kristina climbed into the ring at Gleason’s and began to shadow box. It was just before noon, and the gym, which occupies the second floor of an old warehouse building, hadn’t yet filled up. A few guys ran on treadmills along one windowed wall; across the room, others skipped rope or worked at the ancient, duct-tape-swaddled heavy bag. There is never any music playing at Gleason’s; the only soundtrack is the bell that rings every few minutes to signal the beginning or end of a round; the slap of hands hitting the speed-bag; and an intermittent chorus of voices shouting for a guy called Chicken, whom nobody can ever seem to find.

Kristina jabbed and ducked in quick, staccato flashes, brow furrowed and jaw set. Soon Delen Parsley, whom everyone calls Blimp, put on a pair of mitts and joined her in the ring. He is very tall and very wide, and he towered over her, yawning, while she whaled on him until she tired herself out. “It’s raining men!” Blimp belted. Cross. Jab. Jab. Duck. “Hallelujah!” Cross. Jab. Kristina held her focus, face resolute. Her Golden Gloves fight was just weeks away, and she was starting to get nervous.

Golden Gloves bouts are matched by random draw, so Kristina didn’t yet know who she would fight that afternoon. But she knew she was the least experienced boxer registered, and the youngest. In the previous year’s women’s 125-pound class, the fighter with less experience lost in every single bout. When she drew Amanda Isaac, Kristina looked worried. Isaac frequently spars with Heather Hardy, and Hardy had told Kristina to watch out for her. Her brow was furrowed as she chugged the Pedialyte, and then sat down so Blimp could wrap her right hand, and then her left, in thick white gauze.

When her hands were wrapped, Blimp followed Kristina back to a small corner of the gym where she could warm up. “Little Bit, don't over-think it,” he said. “She’s not that good.” He helped Kristina into her gloves and headgear, then draped a blue satin robe over her shoulders. Top 40 blared out of the speakers until someone pulled the plug; the gym fell silent as the fighters walked toward the ring. They climbed in, touched gloves, and retreated to their corners. Just outside the ropes, an official steadied a large old bell with one hand, raised a hammer, and hit.

The gong reverberated through the air, but the crowd stayed quiet as the two boxers approached one another, moving forward and back, each looking for an opening. Isaac’s first punches were strong, and by the second round, after the two standing-eight counts, Kristina was pausing more than she was hitting. This didn’t bode well for her chances: amateur bouts are scored based on the number of punches a fighter lands, rather than how strong the hits are; the more punches you throw, the better. “One-two!” Blimp called, over and over again, prompting Kristina to throw a jab, then a cross. By the end of the second round, Kristina had avoided a fight-ending penalty, and she survived the third round in much the same way. But surviving wasn’t good enough. She only had two more minutes to show the judges what she was capable of.

The final round began, and Kristina, seeming to realize that it was now or never, came out aggressively. She hit Isaac with a right hook, backing her toward the far corner. But when Kristina picked up the pace, Isaac met her, throwing a series of swift punches. They were fixed in place, pummeling each other, as the bell rang.

Kristina walked back to her corner, and pulled off her headgear and gloves. When the ref called the two women back to the centre of the ring, and lifted Isaac’s hand high above her head, Kristina’s face was expressionless. “Alright, I might've lied to you,” Blimp said, as Kristina climbed out of the ring. “She’s really good.” Kristina shook her head, gathered her things, and sat down to watch Christina Cruz win an easy decision in the next bout.

By the time Kristina got into the back seat of her mother’s car to go home to Greenpoint, it had grown dark, and they circled a few times, trying to find the highway. On the ride home, she vented her frustration. Training for months just to get in the ring and be overmatched is enough to make anyone angry. A few years back, Kristina told me, some female fighters petitioned the Golden Gloves to begin separating women by experience, to make their fights fairer. But the organization said that they would have to wait until there were more women lining up to fight. Kristina doesn’t think there’s much else that can be done. She’ll keep fighting in the amateurs, because she doesn’t have much choice. Deciding not to fight is basically deciding not to box. And she never wants to stop boxing.

Two days later, she was back in the gym. Blimp’s son, a, long-limbed, 6’2” professional middleweight, was waiting for her when she arrived. He called her into the ring and made her go twelve rounds with him. Any mistake and she was on the mat, doing pushups. “I needed that,” she said, afterward. It was back to work, as usual.