Every war film faces an innate cinematic challenge: its subject exists in direct opposition to its form. War destroys; art creates. To show war on film, then—to create even the representation of war—seems, in the abstract, to be an almost oxymoronic concept: if war is an atrocity, the nadir of civilization, and movies are meant to entertain, then what entertainment is there to be found in war?

But like most concepts, war falls somewhere between the poles on the spectrum of horror and beauty. There’s an oft-repeated quote, usually attributed to François Truffaut, that there’s no such thing as an anti-war film: war is seductive and visually powerful, and to show it is to flirt with what’s kept humanity rolling into war throughout its history. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the Italian founder of the Futurists, believed that war was actually beautiful in and of itself. A fascist, Marinetti’s statement was likewise fascistic in and of itself, but it does point to that power of seduction—war is horror, but the portrayal of war is not always so appalling.

Now, thanks to the myriad ways we can entertain ourselves at any given moment, making a war movie has become even more fraught than it was in the early days of filmmaking. Video games have changed the nature of recreated combat; every person below the age of 30 likely grew up with access to games that allowed you to play a soldier in war, and the massively popular Call of Duty has re-cast wide-scale infantry combat as a sort of competitive sport. Not only can you watch fake soldiers kill for entertainment, you can be a fake soldier, killing for entertainment. Making a moralistic argument about the enjoyment derived from this is quixotic; it takes on the tenor of politicians arguing over Marilyn Manson. The reality of the situation is that these games are so widespread, so fundamentally a part of our entertainment culture, that their place in our culture has to be, on some level, accepted, even by people who can’t quite bring themselves to approve of it. And if that’s the case, we can have our qualms with war as entertainment, but the question of whether or not war can be entertainment has been more or less settled.

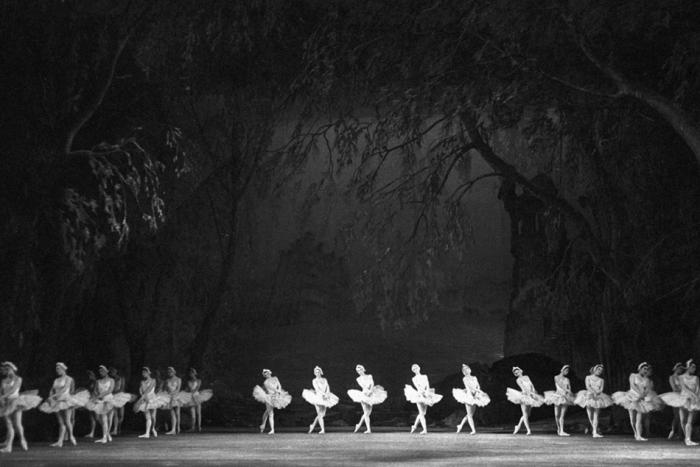

Of course, cinema’s sole purpose is not just to entertain, and some recent war films point toward two contrasting ways of approaching this problem. Let’s start with the traditional. Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper, the highest-grossing American film of 2014, comes from a long line of expensive studio movies dedicated to the subject of war above all—above the combatants, above the civilians, and above the settings in which it takes place. Arguably the best example of this type of war film is Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, which strives to visually represent the idea of Total War by making the camera’s frame so dense with its indicators—bullets, explosions, soldiers, death—that it takes on the integrity of a ballet, or an opera: the language of the drama in question attempts to overwhelm the language of the non-dramatic. And the cinematography only enhances this metaphor, with the camera whirring around the battlefield, considering it from multiple perspectives: we may be with the soldiers on the ground, but we are with all the soldiers at once.

These movies might be entertaining, but they’re also deeply unsettling to watch, designed to provoke anxiety and discomfort. Through that antagonism, they assume some of the burden of their moral grayness. Saving Private Ryan is brilliantly discomfiting, too, but in a humanist way: there isn’t that same smearing. And if American Sniper unsettles the viewer, it isn’t in any way the film intends.

Much of this approach depends, ironically, on scale. The enormity of war is impossible to convey on a screen that can be looked away from, and so these films are also filled with musical scores that envelop you, that invoke majesty and history. Mixed with the sounds of war itself, this music elevates the fighting from human drama to high drama, drama that spans time and place; it’s a ruse, but an effective one. There’s a reason war films often win Best Sound Editing and Best Sound Mixing at the Academy Awards.

Then there’s the other approach, exemplified by Yann Demange’s recent movie about the Troubles, ’71. War is monomaniacal, but it isn’t uniform. For every World War II, every conflict with a clear moral binary and narrative arc, there are a dozen more that are gray and undefined. The conflict between the Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland did not have a Hitler, and Demange accordingly takes a different approach to making his film than Spielberg did with Ryan. ’71 is shot mostly handheld, with quick zooms, sloppy and real as looking through binoculars. Where the combat in Saving Private Ryan often felt biblical in scale, even when Spielberg went handheld, the camera in ’71 rides its characters so closely that the momentum destroys any sense of a larger unfolding. It’s urban warfare at its most claustrophobic, and it serves a purpose: Saving Private Ryan never lets you forget the apocalypse unfolding around its soldiers, while ’71 never lets you think about it when the chase is on.

For example: ’71 tells the story of a British soldier, played by Jack O’Connell, lost behind Catholic lines in Belfast, but the narrative exists largely in the moment, with little meta-narrative or context for what’s happening, which is of a piece with Demange’s desire for visual immersion. The main thrust of the film begins when the soldier’s unit goes out into the city and becomes involved in managing a riot. Chasing a boy who stole a British rifle, the soldier is separated from his unit, and, forced to flee by Provisional I.R.A. members, he takes off through the alleys of the city. When the soldier starts running, the camera goes running with him, and the scene becomes a dazzling exercise in velocity; bullets from the pursuers’ guns are kinetic sensations rather than visual, and that feeling of motion tells us more than any observed phenomena, because what we can observe is so consistently unclear.

In both its form and ambiguity, ’71 is reminiscent of The Hurt Locker, Kathryn Bigelow’s adrenaline-addled Iraq film. Unlike American Sniper and Saving Private Ryan, the subject of these movies is not war itself. Instead, ’71 and The Hurt Locker are concerned with the impact of combat on combatants as the combat takes place. And to do this, the most effective means of portrayal is placing us directly among those combatants—practically inside their helmets. This visual style of speed and chaos works particularly well for these conflicts. In The Hurt Locker and ’71, both the Iraq War and the battles of the Troubles are fought in fog and confusion, by people whose enmity toward each other exists on a sliding scale. The Troubles makes for a particularly convenient exercise in overlap: its combatants looked identical to each other. These movies might be entertaining, but they’re also deeply unsettling to watch, designed to provoke anxiety and discomfort. Through that antagonism, they assume some of the burden of their moral grayness. Saving Private Ryan is brilliantly discomfiting, too, but in a humanist way: there isn’t that same smearing. And if American Sniper unsettles the viewer, it isn’t in any way the film intends.

By applying the visual and stylistic tropes of World War II movies to the wars in the Middle East, though, American Sniper creates a strange atmosphere. Plot and characterization aside, the “enemy” is extensively othered by the camera. We see women and children almost solely in the guise of combat, and a demonic, mystical Syrian sniper is treated like an odd savant, captured in glimpses, jumping between buildings and hidden in wait. The Syrian sniper is one of the only times the visual perspective leaves Bradley Cooper’s Chris Kyle, and it’s instructive: Eastwood uses that respite from Kyle’s overwhelming competence abroad and overwhelming gloom at home, both literalized in countless ways, to show a pure, unadulterated enemy. War on film can be obscure and puzzling. It can also be clear as a photograph.