“Hello, I’m Henry.”

A friend of mine recalls that Dr. Henry Morgentaler said these words to her in the mid-2000s, warmly introducing himself before performing her abortion. The room, with its familiar table and stirrups, was clinical, sterile and cold, yet the atmosphere friendly, the famed doctor short and wearing scrubs. “It took me a minute to believe that it was him,” she tells me. “Every time I’ve read about him, it has always been his full name. It’s his last name that has become the symbol of the man. It’s like this wasn’t Dr. Morgentaler, abortion crusader, Holocaust survivor. This was just Henry.” In her surprise, and under the influence of the drugs she had been given, she managed to stammer out how nice it was to meet him, and how grateful she was for all that he had done.

When she tells me about that day she relays that security was tight, with cameras, heavy doors, and a thorough check of her identification. She tells me of the countless forms and questions, a meeting with a kindly counselor, a cold inner waiting room where she was given a blanket and an opportunity to change into the nightgown she was asked to bring with her. It was blue with butterflies printed on it, and she found something comforting in being allowed to wear her own clothes.

About five women of varying ages waited with her for a doctor in that secondary room that day. None of them spoke, pretending to read the out-of-date magazines to avoid small talk. One woman, her hair pulled up into a ponytail, was crying, her knees drawn up on the plastic chair she was told to wait on.

“I was sure about the decision,” my friend tells me. “I was in a happy place in my life, my relationship. I had no guilt or doubt or fear. In the second waiting room, I realized that for others, this was one part of another type of story. One of trauma and conflict and judgment and guilt. I was one of the lucky ones.”

Her use of the phrase “lucky ones” sticks with me as the country reflects on the complex personal and public life of Dr. Henry Morgentaler. When great leaders of social change die, we often write in our tributes to them that we are ungrateful, that we have taken their gifts for granted. It is true that so many victories for women are forgotten through generations; our right to vote, to work, to be educated, to not be beaten or raped by our partners. But abortion always seems to be an entirely different matter, a tenuous victory constantly under a shadowy conservative threat, one that those who value women’s dignity and bodily autonomy cling to and devote their lives to defending—even when their own relationships with women are sometimes complicated and uncomfortable.

Early morning yesterday, at the age of 90, Morgentaler died peacefully of a heart attack at his home in Toronto. The news reports of his death paint him as a controversial, polarizing figure, viewed by some as a hero for the rights of women, and for others nothing more than a murderer. For the pro-choice set, his death is bittersweet—we are gutted by loss, but grateful he lived a life as long as he did, a man who spent five years in the Nazi concentration camps of Auschwitz and Dachau only to face, by his own brave actions, the anxiety of legal retribution, aggressive protests, physical attack, the firebombing of his clinic, and countless death threats.

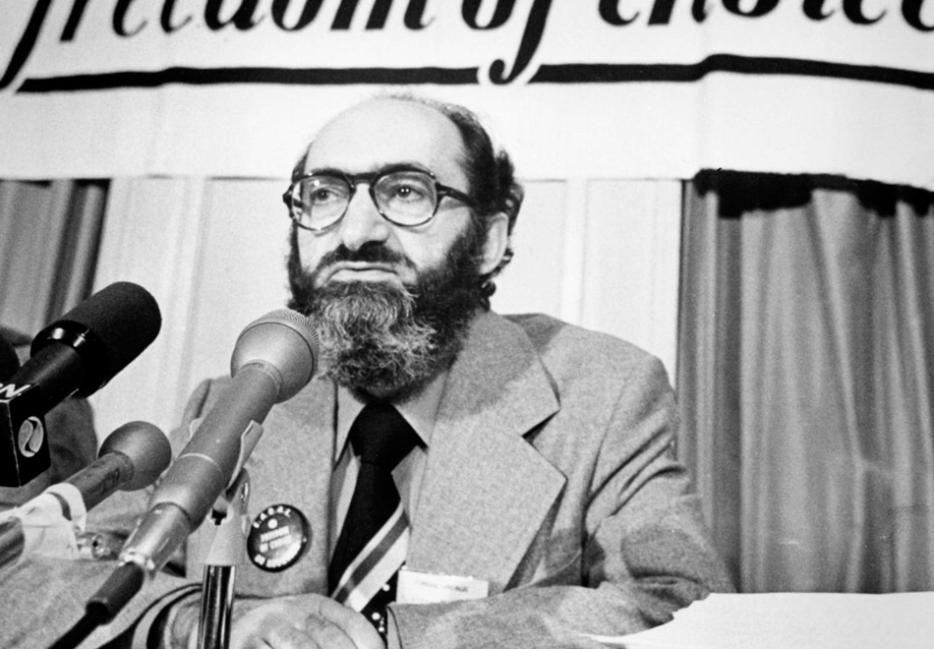

In 1967 the Polish-born family doctor emerged in Montreal as an advocate for the rights of women not to carry an unwanted pregnancy. In doing so he exposed the countless risks of “back-alley” abortions, speaking for those who were shamed into not speaking for themselves. That year the unlikely activist gave a speech before the Commons Health and Welfare Committee in the hopes of changing Canada’s strict abortion law and saving women’s lives. When that change didn’t come, he started performing illegal abortions on those who asked for his help. In 1969 the government altered the law to lessen but not remove restrictions, and Morgentaler opened his first clinic, one that was raided multiple times into the early seventies. The defiant doctor would eventually serve 10 months in prison, while, on the outside, the debate over abortion escalated across the country. Undaunted, Morgentaler opened more clinics upon his release.

He wasn’t perfect. A Globe and Mail obituary published yesterday referred to him as “a consummate philanderer,” with three marriages and countless affairs under his belt. It was a personal flaw that Morgentaler himself acknowledged—maybe excused—telling the paper in 2003 that, “deep down, with me, I was afraid they would leave me, or stop loving me. It was a psychological strategy to make sure there would always be a woman who loves me.” It is easy to conclude that his love of women was his private ruin, his sins against them perhaps forgivable in the face of his inconceivable courage to defend their rights. He was, of course, merely a man—he was that day when he greeted my friend before her abortion, that day in 1967 when he spoke in front of that government committee, that day in 1988 when the Supreme Court struck down Canada’s abortion law as unconstitutional, and that day in 2008 when Governor General Michaëlle Jean controversially named him to the Order of Canada.

Although she wants to, my friend can’t publicly tell the story of her day with Dr. Morgentaler in her own words. “I am grateful for the rights I have, but also grateful that I don’t owe anyone an explanation,” she says. “It’s my choice who I tell about the decisions I’ve made.” She’s not ashamed, nor does she regret it, and has spent much of her life devoted to making sure the same choices are available to other women. Together we acknowledge that threatening shadow that makes our grip on reproductive freedom constantly tenuous, that makes her anonymity necessity, that makes Morgentaler so important. Choice is hard won, and is a fight that we can never become complacent about.

Over his lifetime Dr. Henry Morgentaler was a tireless advocate for the right for women to have reproductive freedom and access to care because that fight was a necessity he couldn’t ignore. He performed thousands of abortions, trained more than a hundred doctors, and continued to open more and more clinics across the country. He gave us choices when the law said we weren’t allowed to have them, believed abortion to be a basic human right, and is a valuable reminder that one need not be a saint to be a hero. His legacy affirms an ideal that every man has the capacity, even under threat of death, to devote himself to a cause that brings solace to many. We are all lucky to have had him. All that Henry has given us should not be taken for granted, and for so many women—so many Canadians—never will be.