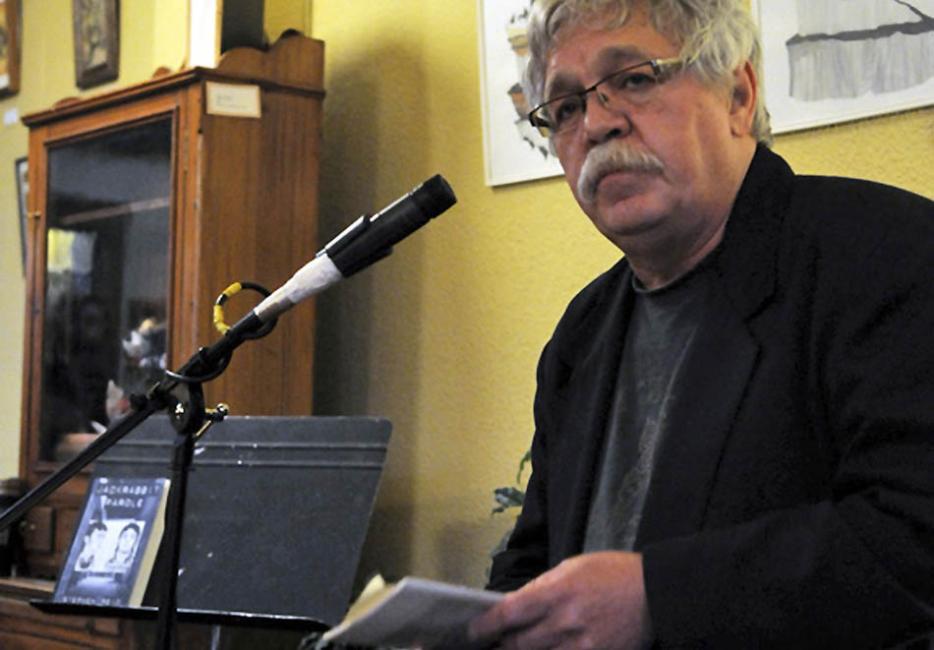

Stephen Reid, once a well-known bank robber, member of the Stop Watch Gang, has spent more than 25 years behind bars. There is a lot one could say about that, but most inmates don’t. Reid didn’t know he was a writer until he landed in maximum security in the 1980s. Solitary confinement enabled him to complete a novel, Jackrabbit Parole, based on his own experiences.

Now comes A Crowbar in the Buddhist Garden, a collection of his essays subtitled Writing From Prison. But the selections are not from his most recent stint at William Head Institution in Victoria, British Columbia, where prisoners’ voices—since the Conservative government’s omnibus crime bill put emphasis on keeping more criminlas in prison longer—are more often quelled than encouraged. Communication with the outside world is strictly controlled by Correction Services Canada and often denied.

“Any public expression is actively discouraged. It’s actually getting quite harsh,” he says in a telephone chat. Other inmates support his statement. The annual play production by the inmates at William Head still goes on, but its future is iffy, according to a former participant because of the exposure of prisoners to members of the public.

And why would prisoners want to write? “To show that we are human,” says Reid, quoting an Ursula Le Guin story. His 60-plus years are showing, the once black hair now grey but still thick, but his soft voice is as persuasive as ever. “There are real people living here,” he says, and there is something to be learned both for the prisoner who writes and for the public those words might reach. (Reid’s work has appeared not only in the mainstream media, including Playboy and Vancouver Magazine, but also in the national inmate journal, Out of Bounds.)

Still, Reid says, “I hate it when people call writing therapeutic.” Therapy is something to quell the anger, “writing is a totally different thing. Writing is about other people. It’s about trying to find the universal stuff.”

There is no question that Stephen Reid is the genuine article: an artist. Reid was in maximum security in Kingston when he first took up writing. He wrote Jackrabbit Parole all in a rush (“it poured out of me”) and in 1983 sent the manuscript to Susan Musgrave, then writer-in-residence at the University of Waterloo. It was love at first read. With Musgrave’s help, the book was published in 1986, although Reid remained in prison. That same year, Musgrave and Reid were married in a prison ceremony at Kent Institution in Mission, British Columbia. When he was granted parole in 1987 they moved into cottage by the sea near Sidney.

Poet Lorna Crozier remembers not expecting much when, prior to meeting Reid for the first time, she dipped into Jackrabbit Parole.

“I loved it,” she says. “I was blown away with his skill.” The book was full of metaphors and similes she’d never seen before. “Aristotle says you cannot be taught (metaphoric language), you have to have an instinct for it. Stephen has that instinct.”

She has wondered what it would be like to be a writer in prison. In the essay, “Born to Loose,” Reid writes, “Writing in prison is like trying to juggle chainsaws during Chinese rush hour.” You couldn’t say it better any other way.

Reid is humble, even apologetic, about his limited output since Jackrabbit. “I’ve got about six failed novels on the go. I’m not a prolific writer. (And) I just didn’t write for about ten years.” Writing was difficult on the outside, where he was a husband, father, breadwinner—sometimes teaching, doing things he learned in prison such as making native drums—and exposed to the temptations of drugs. Not even his wife was aware of what lay behind an intractable addiction until long into their marriage. In the essay “Junkie” he writes, “The blood broke into two rivulets along the smooth skin of my upper arm . . . . Paul returned the syringe to its coffin-like case and dabbed at my arm with a soft white cotton ball.” Paul was a doctor and a pedophile who picked up the eleven-year-old Stephen in his Thunderbird and as a prelude to sexual abuse, injecting him with morphine. He wrote that essay in 2000, after returning to jail with an 18-year sentence for a Victoria bank robbery gone wrong.

The money was to pay back his drug dealers. He tells the story of his disastrous return to sticking up banks in 1999, in “The Last Score”: “June 09, 1999, 9:15 AM Pacific Standard Time. For me, emerging from the Shell station toilet, my head rocking from a fresh jolt of heroin and cocaine, and twenty minutes behind the nine ball, this AM is about to become anything but standard.” In all his years as a robber—going back to his twenties—Reid “never got mangled before a score—not since I was a juvenile throwing corner stores up in the air.” The author doesn’t grant himself any redemption. In “A Man They Loved” he writes of his daughter: “She is a wise young girl who has learned to separate what her dad has done from who her dad is, something even her dad has yet to learn.”

Only during his most recent incarceration—on March 6 he was granted day parole to attend a treatment centre—has Reid found escape from the hounds of addiction, through use of an opiate-blocking drug administered at William Head. His health has suffered over the years; he had heart surgery following a parole in 2008. But when asked about his condition, he says only, “it is what it is.”

Most of the writing in A Crowbar in the Buddhist Garden is not personal. Several pieces relate aspects of native culture in the prison system, of interest since Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers’ March 7 report underscored the disproportionate size of the aboriginal prison population.

William Head caters to its First Nations inmates with a carving shed and a gathering place. “There are a hundred or so inmates,” says Reid, “and 30 or so are natives. A lot of them emerge as spiritual people.” Both in prison and outside, he has been attracted to “a spirituality that’s all-inclusive. . . .” At William Head he enjoys the communal existence in the Salmon House, where elders cook together, eat together, and live together and he credits Correctional Services Canada for recognizing native culture for what it is.

The impulse to write is strong in him and being published again has given him renewed impetus. “I hope to finish at least one more novel.” He says he loves fiction because of the free rein he gets to express himself, but he admits that after Jackrabbit, “I got distracted by the idea of a persona. It was the toxicity of fame. I fell into that for a while without recognizing it.”

Now he knows that as a writer, he has to “be as courageous as I can. You have to have the courage not to be liked. I never want to be safe.”