Music and fiction collide in a vast number of ways. Many novelists, such as Colson Whitehead and Carola Dibbell, have worked as music critics, and the likes of Jonathan Lethem, Michael T. Fournier, and Alan Warner have contributed to the long-running 33 1/3 series of books about specific albums. Memorable novels have been written about fictional musicians, from Ben Greenman’s Please Step Back, which traces the ups and downs of a Sly Stone-like funk visionary, to Leni Zumas’s The Listeners, about a former member of a postpunk band trying to overcome her traumatic past.

A much smaller group of writers have taken cracks at placing real musicians at the center of their novels. Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings deals in part with a 1976 shooting at the home of Bob Marley, referred to in James’s novel as “The Singer.” (“The reason I went with The Singer instead of his name was because I wanted him to be mythical,” James said in an interview with Midnight Breakfast.) Camden Joy’s novel Boy Island featured a fictionalized version of David Lowery of Camper Van Beethoven, with whom the novel’s narrator goes on tour, and the aforementioned Whitehead’s Sag Harbor features a brief cameo by the 1980s hip-hop group UTFO, who help settle a dispute between the narrator and his friends concerning the lyrics of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message.”

Sometimes this invocation of real musicians can be audacious: consider Jack Womack’s 1993 novel Elvissey, whose protagonists travel from a corporatist-dystopian near future to an alternate Earth to kidnap that Earth’s Elvis Presley. In the near future where much of the novel is set, Presley has become revered as a god—one character has a job teaching “Comparative Elvisims at Harvard Divinity”—which leads to the desire for an easily controllable messiah. In Womack’s novel, however, this alternate Elvis, known as “E,” turns out to be a racist sociopath, and is first introduced in the aftermath of a murder. Still, he’s a hell of a singer.

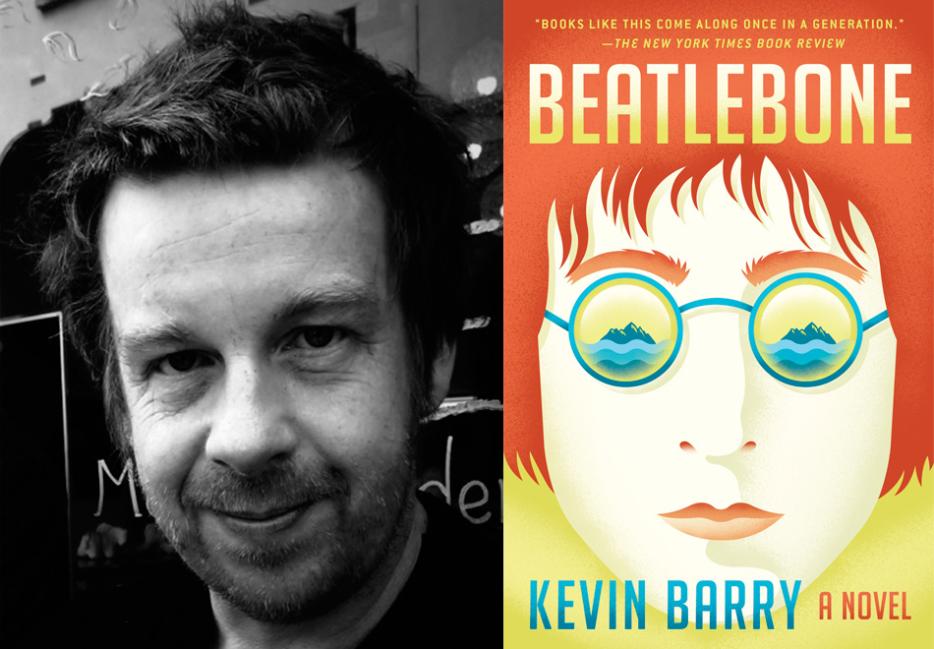

Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone falls somewhere between the historical and the surreal. Barry is no stranger to the latter approach: his award-winning debut novel City of Bohane was set in a strange city in the middle of the twenty-first century, while the stories in his collections There Are Little Kingdoms and Dark Lies the Island explore a range of styles and expressions. Beatlebone is, on the surface, more traditional: it follows John Lennon on a quest through the Irish countryside in search of an island he had purchased there years before.

But much of the strength of Beatlebone comes from how it defies expectations. The repartee between Lennon and Cornelius, the local man tasked with driving him around, takes on an increasingly surreal familiarity. And Lennon becomes haunted both by local communes and his own memories. As Barry put it to me, “time is slippery and there are strange forces at work all the while.” Readers looking for a heroic story of John Lennon may be disappointed; readers looking for a uniquely structured story of a man grappling with his own past, which happens to star John Lennon, will find much more to savor. I spoke with Barry about the four-year process of writing Beatlebone (which is out in paperback this week), his own experience of the landscape in which it is set, and what’s coming next.

*

Tobias Carroll: Maybe we should start with the basics. What first drew you to John Lennon as a figure to write about?

Kevin Barry: My bicycle, is the short answer. I got into cycling in the summer. I live in County Sligo in Ireland, and I go out west to County Mayo, out through Clew Bay, where he owned that island. For years, it had sat idly there, in the back of my mind—this odd little fact that John Lennon used to own one of those tiny islands down there. And I found myself thinking, “Which one?” And I started to research it. I wasn’t sure what I was up to—I’m never sure what I’m up to, as a writer. It’s always operating by gut instinct. I wrote a little piece for radio about the fact of John having an island on the west coast of Ireland; I wrote a little essay about it. And one dark, hysterical morning, I found myself scratching down some lines of dialogue, and I thought, “Uh-oh! I’m going to try this as a long piece of fiction, aren’t I?” It was a scary realization, because he’s such an iconic figure. It took a lot of work to take a voice for him.

Is his ownership of the island something you’d always been aware of?

It’s something that lodged in my brain years ago. It was a well-known little story in Ireland in the ’70s and so forth, right before fading with the mists of time. When he died, the island was sold and the proceeds were given to an orphanage, actually. It went back into private ownership. It’s owned by a sheep farmer now; there’s sheep out there. The weird thing is, I’ve never been a particularly fanatical Beatles fan. I was always very much leaning towards the Church of John when it came to the Beatles; The White Album is a favorite record of mine. And Plastic Ono Band, some of the early solo records, are special to me. But it was a surprise to find myself sitting down to write a novel with John Lennon as the main character in it. It’s not something I would have predicted. It was a long process, to try to get a voice for him on the page, because every reader’s going to come into the book with an expectation of what he should sound like. I had to try a lot of techniques and methods to try to get something that I was happy with.

For some people, Lennon is a heroic figure; in more recent years, the fact that he was abusive has been brought up more frequently…

He is a divisive figure. What’s really interesting about trying to get him down on the page is that his tone is very changeable and capricious. I was very careful not to do any traditional research amongst the texts, among the books. There’s so much of that stuff; if you open that cupboard, that whole world of materials falls out, and you get smothered by it. I did watch a lot of YouTube clips of chat show interviews with him, just trying to get the intonation of voice. He’s very capricious in tone. He will go from very fluffy and light and charming to very dark and quite thorny within the course of a sentence. To try to replicate that on the page in a believable way is difficult. It took a lot drafts, it took a lot of grunt work. It took a lot of heavy lifting. I wrote hundreds of thousands of words to whittle away to get something that I was happy with. My starting point was from a point of devotion and fandom. I am a big fan, and it was written out of that sort of poignancy, really—that he was a great artist who should still be among us.

You zero in on his time spent in primal scream therapy for part of the book. When in the process did you decide that you wanted to focus on that in the novel?

When I realized that he was on this kind of madcap mission or journey or quest to get to his island, naturally, it occurred to me: what’s he going to do out there when he gets there? And the whole fact of his background in primal scream, that kind of Reichian therapy, seemed—yeah, he’s going to go to his island to scream.

I had to go all method actor on it. I did eventually make my way to the island myself, and I did try some primal screaming out there with, I would have to say, mixed results. Increasingly, whether I’m writing this novel or short stories, lately I kind of like to write on location: go to the place I’m writing about and get the material down while I’m there. Almost like a documentary approach, I guess, and a way for me to keep the writing fresh and immediate. This story, primarily, is about John Lennon as an individual, but it’s about an artist—how any artist struggles to get at their materials. How do you make a record? How do you make a novel? How do you make anything creative? It’s about going into your dark places and using the materials that you find there. Primal scream therapy is about doing exactly that, uncovering all sorts of buried childhood pain and so forth. It was a way, as well, to put him into difficult situations, where he falls in with the remnants of a primal scream commune. It means that they have this possession called The Rants in the book, where they try to strip each other down to the bare bones of who they are. It was crazy, intense stuff to write. It took a lot of drafts and work to get to a place where I thought I could let human eyes fall on it at all. It was very dark in the initial drafts. It remains quite dark in the book.

That whole world of communes and primal scream therapy, and alternative living groups, I remember coming into the west of Ireland when I was a kid in the ’70s into the ’80s. That version of the Irish west almost never shows up in Irish literature. When you read the literature of the west of Ireland, it tends to be about the farms and the small towns and so forth. But there were a whole lot of freaks there as well, and I very strongly believe that they improved the place. They made it a far more interesting world.

Was your process for writing this different than it would have been had it not had John Lennon as a central character?

I kind of threw the kitchen sink at it. There were so many approaches and methods used for what’s a pretty short novel, a 54,000-word novel. I mean, there’s an essay in the middle of it. There are play texts. What it most resembles is a kind of old-fashioned play for voices, a radio play. Its primary engines are dialogues and monologues. The dialogues between John and Cornelius, they really power it along. The parts where you turn the pages really quickly—weirdly, those turn out to be the pages where you have to work at it really, really, really hard. I got through eighty, ninety, one-hundred drafts of those dialogues to try to get them flawless in their flow. I was convinced that this going to be a really short process, that it was going to be six months in and out, that I would have an intense burst of glorious prose and then would be finished. Four years later, I crawled from my work shed with the tablets of stone, having been through an atmosphere of mounting hysteria.

I think the first two and a half, three years were really difficult on me, actually. The last year was great, great fun because I felt that I had the voices, and when you have the voices, you can invent at will. I broke the back of it, weirdly enough, in Montreal. I spent a year in Montreal, in 2013 into 2014, that very cold winter. Minus-25 degrees Celsius turned out to be ideal conditions for the novel, because there’s nothing else to do. I squirreled myself away, a lot of the time, in the Quebec National Library, where I didn’t have the wi-fi code, crucially. I got a lot of work done there. I weirdly associate Montreal with the novel; I managed to get a little mention of the city later on in the text, as a nod to that.

You brought up the fact that a lot of the novel is two people talking, one of whom is incredibly well-known. How did you make Cornelius’s character a suitable partner for him?

A central ongoing joke of the book is that Cornelius is a legend in this particular world, and he’s just got this guy tagging along with him. Everyone they meet is more impressed with Cornelius than they are with John. Cornelius is the alpha male in the pair as they rattle around the west of Ireland in this old van. Cornelius is an amalgam of various characters I’ve come across myself through the years. He’s tricky—you’re not sure what, exactly, he’s up to. He’s got a roughish charm. There are certainly elements of myself in him, in his speech and the way he talks. It was when the two of them started to play off one another that the thing stood up on the desk for me and started to come to life, and I realized that, in many ways, it’s a novel in a very antique mode. It’s essentially Don Quixote tilting at windmills, and the quest, trying to discover the meaning of life.

Cornelius is also a type of character that Saul Bellow used to describe as a “reality instructor.” Saul Bellow would always have [this] character who would appear in his novels—the guy or the girl who came along and said, this is how you get true in life. Cornelius is that. He’s operating in a very unusual form of reality, where things are unfixed and time is slippery and there are strange forces at work all the while. I’m never quite working within the realm of realism. Where I operate is out on the edge of believability all the time. I want the reader to be going, “No way.” Maybe, just maybe, there’s enough to let you get away with this. It’s a very risky place to operate as a writer, but it’s very interesting as well. And a constant game you’re playing with the reader—how far can I bring this very tall tale? That was the reason I wanted to place that autobiographical essay bang central in the book, where it acts as a kind of qualifier, where you break the screen and show the reality underpinning this, where it came from—the facts of John’s life and what I brought to it myself as a writer to try to give it emotional heft and weight.

The inclusion of that reminded me of the structure of John Edgar Wideman’s novel Philadelphia Fire, and the moment where Wideman enters the narrative of the book to provide a different perspective on some of the history that he’s writing about.

I’m going to suggest that there’s an increasing trend among novelists to come in and out of their fictions. When you’re writing a novel or short story, there’s a sense now that you have to show the workings there and declare, “Yeah, this is a made-up thing, but this is how we’re doing it, and this is why we’re doing it.” Increasingly, when I’m sitting down at my desk, I’m not thinking about writing a novel or short story; I’m thinking about writing a book. I think a lot of the forms and genres are starting to rub up against one another and collide in really interesting ways. When different forms and genres touch each other, hopefully sparks come and you get something that’s new. What I love about the novel as a form, and what will keep me going back to it, is that I think that it’s infinitely capacious. It can take pretty much anything you throw at it. As long as the reader is having a good time page by page and line by line, they’ll follow you to the ends of the earth. I have an overall structure in mind when I sit down for this, but I’m really concentrating on it sentence by sentence, and trying to pack as much intensity as I can into each of the sentences.

As they’re driving around the island, there are a number of references to the music of Kate Bush–

She gets a hard time in the book.

Was she in there as a kind of musical foil to John Lennon?

[That was] one of the few bits of actual research I did: the book is set in May of 1978, and I did Google to find out what was in the charts at this time in Ireland. What would have been on the radio, if he had been drifting around the countryside? And it would have been “Wuthering Heights,” by Kate Bush. It was the big number one song of that era. It was fun to play with. I was myself a huge devotee of Kate Bush as a young boy and adolescent, to a feverish degree, and I remain so until this day. I’ve had some very disappointed Kate Bush fans complain to me about her treatment in the novel. I think she’s wonderful. The Kate Bush music would have been, in many ways, much more suitable to this wind-blasted landscape than John’s. For me, what was fun was to imagine if he had gone down a different road as an artist. If he had gone into a more avant-garde, experimental mode. Into more of the kind of world that Yoko operated in, and operates in—more the art world. The world that Scott Walker operates in, for example. He started out as a pop artist and became a more experimental artist. It was fun to imagine John in that world, and things going very badly.

The most fun I had in the novel was the studio section later on, where it’s John and his engineer, Charlie Haimes. I thought that was fun. When things are always going dramatically badly, it’s always a fun point in a book. Apart from the essay, that was the section I wrote most easily and effortlessly. I love what-if scenarios, and imagining John as an experimental artist … There was actual stuff to play with. In the late 1960s, he was going in that direction on The White Album and tracks like “Revolution #9.” He was interested in experimental music. But, as we know, he drifted back; his last record, Double Fantasy, is as pop a record as he ever made, and as sugary-sweet a record as he ever made. After the Beatles, he was going in an experimental vein before having this period where he was blocked for a few years because he was too happy. There wasn’t enough strife and trouble in his life to come up with stuff.

The thing about listening to music as you write, as you work—I did listen to The White Album to a slightly obsessive degree as I was working on the book. It’s a glorious mess of a record, and I wanted this to be a glorious mess of a novel, to be as wild and as knotty. I listened to a lot of contemporaneous stuff as well. What’s interesting about that period in rock history is, we realize now, that it was finite. The great stuff only really persisted for so long, and we went into a different and lesser era, I think. You could say that great stuff was happening from the mid-1960s to the late ’70s, early ’80s, and after that—not that there isn’t great music being made now—the really classic, iconic stuff has a period of about fifteen, sixteen years. It all seems to be enclosed in history. I was hoping that this would be the end of my rock book experiments, but I find myself lately getting very obsessed with that Altamont Rolling Stones documentary. I re-watched it again and again. It’s such a rich era, full of color and character and crazy shit happening all the time. It’s always amazed me that there aren’t more great rock novels.

They’re almost always disasters. Even favorite novelists of mine, like Don DeLillo, wrote Great Jones Street, his rock and roll superstar novel, and it’s far and away his worst book. It just doesn’t work out. I think, often, the problem is that they use invented musicians and invented rock stars, and it never convinces. At one point, early on in the first year that I was working on Beatlebone, it was so difficult to get the voice, the thought did cross my mind that maybe I should make this an anonymous rock star on this journey to the west of Ireland. Maybe that would be easier. But I thought, no. That’s shying away from the difficulty of it and the real audacity of it, to try for the voice in such an iconic figure.

In terms of fictional musicians, I found the main character of Stacey D’Erasmo’s Wonderland believable, but that character is a cult musician playing smaller venues than a rock star headlining at arenas. I think the sense of scale makes a difference.

As I was writing the book, I was trying to think of examples of real-life cultural figures being placed into fiction well, and there are so few. I did think to mention Don DeLillo in a more positive light: in Underworld, he re-creates Lenny Bruce’s routines, and does so brilliantly. And in Libra, the way that he does real-life figures like Jack Ruby and Oswald is stunningly well-done. But it’s surprising how little of it is there. I guess it’s because it’s so difficult. I started Beatlebone in a glow of glee, thinking, “This is a great idea—how come nobody has done this before?” And about three weeks in, I was going, “Oh, fuck, this is so difficult, this is so hard, to make any of this believable.” It was four difficult years, but when you’re doing a project like that, when you bring home to any degree that you’re satisfied with—and I am happy with it—it gives you a lot of confidence to take on other improbable and ungainly projects.

Are you working on something new now?

Weirdly, this has opened up a lot of possibilities for me. For example, I’m really interested in writing more essays, and maybe working more on plays. I’ve worked a little bit in theater, and I’ve got a couple of play scripts on my desk at the moment. In terms of the next book, I know what it’s going to be—it’s going to be a second novel set in the phantasmagorical city of Bohane. I’m going back out to that strange place to do another book. I’m pretty sure that I’m not going to be doing a trilogy there. I always knew when I was writing that novel that I was at least doing a second book there. The world of it was working; the city was a good character. When you build a little city, it feels like real estate, and you want to get your worth out of it. That’s definitely the next novel. I’m going to return to the city of Bohane and see what’s happening out there.