William Gerhardie was 27 when his first novel, Futility, was published. Seventeen years later, his last book entered the world—though it would be another thirty-eight years until his death in 1977. In the past year, the Brooklyn-based press Melville House has released two of his novels, Futility and The Polyglots, in new editions. They boast quotes citing Gerhardie’s chops as a comic novelist, and cite some impressive credentials, including glowing blurbs from Edith Wharton and Evelyn Waugh. Finding abundant comedy in the misadventures of the aristocracy, the novels take as their backdrop the Russian Revolution and its aftermath—a period fraught with conflict, change, and fate. They also, however, illustrate broader issues with the aristocratically comic novel—and with comedy of the upper classes as a whole.

Futility is narrated by one Andrei Andreieich, an Englishman who, like Gerhardie himself, was raised in Russia. Over the course of several years, he repeatedly encounters the family of Nikolai Vasilieivich, whose fortunes shift from aristocratic splendor to panicked flailing as the revolution uproots their way of life. Their life already tenuous due to Nikolai’s failure to divorce his wife (and his serial affairs), the family wanders throughout Russia and its neighbors. “We are a chain,” Nikolai tells Andrei at one point. With his relative distance from the family and his desire to solve their marital difficulties through a complex series of arranged marriages, Andrei seems an archetypal comic narrator: bumbling yet charming, well-intentioned yet doomed to fail.

Over the course of the book, though, Andrei drops more than a few undeniably racist words and phrases. Here’s Andrei describing a musical performance: “‘Tell me,’ whined Nigger voices, ‘why nights are lonesome.’” Later, in the midst of war, there’s a reference to “the Christian city seized by a heathen yellow race.” And, after learning the paternity of another character, Andrei notes that “I thought that I could now discover something Jewish about her pretty face.” This isn’t necessarily an uncommon event when reading a novel by a white person written nearly a century ago, but its effect is one of imbalance: It’s harder to write these off as a shameful product of their time, as they clash directly with an empathic sensibility often found in comedy.

Previously, Andrei had been a familiar comic type: The straight man in a sea of eccentrics and grotesques. When his own prejudices are revealed, with no reflection or consequences, Andrei becomes as much of a grotesque as anyone else, throwing the novel’s balance out of whack. As Conor McKeon argued in a 2011 Splitsider essay on political ideology and comedy, “the tilt of truly effective comedy, comedy that affects and resonates, is either inwards or upwards.” With this maneuver, suddenly Gerhardie’s narrator loses his inclusivity, cutting himself off from a portion of his previously established humanism. His “us” is no longer an open group—and, suddenly, his observations of the quirks and foibles of the upper class become much more troublesome.

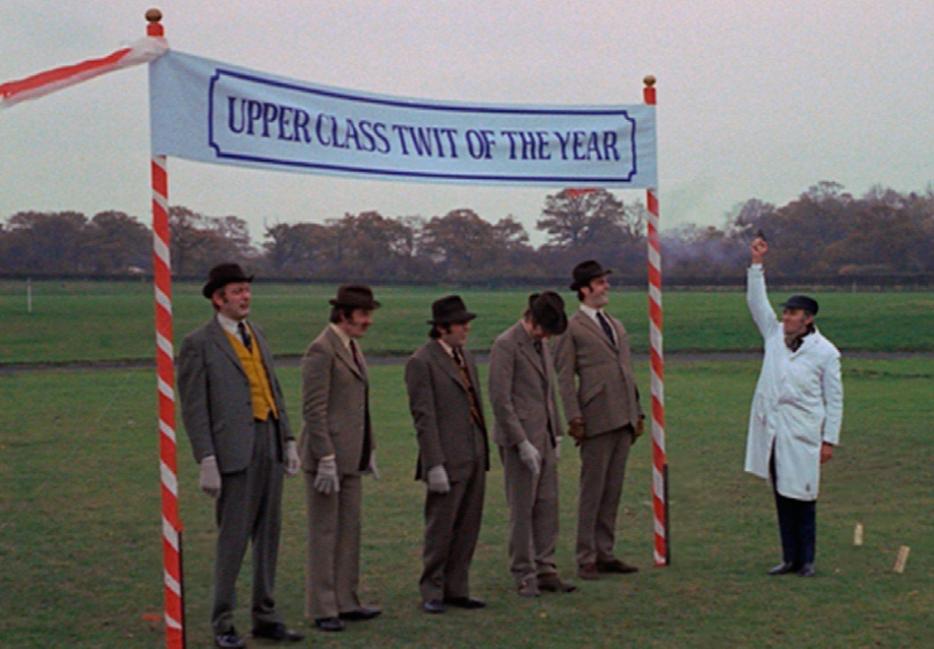

Comedy taking aim at the upper classes has a long and venerable history, from ancient Roman drama to Shakespeare to fiction by Waugh, Wodehouse, and Wharton to films like Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve. But most authors have the sense to honor one simple tradition: In comedy, it’s often best to depict the most sensible characters as being from more humble origins. Consider the valet Muggsy in The Lady Eve, who’s the only character to notice Jean Harrington and Eve Sidwich are, in fact, the same person. Similarly, the Jeeves and Wooster stories wouldn’t have the same kick were it an aristocrat constantly one-upping his employee. It’s a trope, but it’s a trope for a number of reasons: It allows room for subversion, and it allows the idle rich to be taken down a peg. If Monty Python’s “Upper Class Twit of the Year” sketch took as its target twits of a more working-class background, it would play out as far more mean-spirited—and nowhere near as funny.

This is also why reading Evelyn Waugh’s 1938 Scoop in this day and age can be a cringe-worthy experience. Certain elements tap into well-worn comic tropes: mistaken identity, pompous aristocrats, and the staple of someone in over their head—in this case, the young journalist William Boot, mistakenly dispatched to cover war in the nation of Ishmaelia. Waugh’s own sympathies do not seem to be with the idea that African nations are capable of their own governance, though, and while his underdog journalist emerges as the novel’s hero, the African nation he visits (and its residents) becomes the intended object of the reader’s derision. From there, at least, a privileged vantage point works against comedy’s spirit of inclusiveness.

A better model can be found in Edith Wharton’s The Custom of the Country, in which there is no moral center, and a sense of amoral one-upsmanship in the service of economic success takes control. As Wharton’s protagonist, Undine Spragg, makes her way through successive New York social circles, she leaves lives destroyed in her wake through a series of marriages skewer social mores, hypocricy, and old guards social and religious alike. The humor here is entirely bleak, which allows for a kind of relief in the reader. Does that relief stem from Undine’s amorality, Wharton’s wit, or the moral ruin the novel portrays? The humor here sits in contrast to the emotional devastation visited on the novel’s characters, but it’s all the sharper for it.

That quality of humor in the face of tragic events may well be why Gerhardie’s 1925 The Polyglots succeeds in ways that Futilty does not. On the surface, the plots are similar: An earnest young man, an eccentric family, numerous marriage plots, the rise of the Soviet Union. But what makes the difference here is how Gerhardie uses empathy—how this novel’s high-born narrator finds common ground with people from diverse backgrounds. There are, to be sure, a few moments that will inspire twitching, but those moments, at least, seem intentional, stemming from the narrator rather than the author himself.

Here, the narrator is one Georges Hamlet Alexander Diabologh, who encounters his cousins, the Vanderphants, while on a diplomatic mission to Japan; soon, he falls in love with one of them, Sylvia. Their courtship runs throughout the novel, as their relationship falls victim to the sociopolitical changes occurring around them. Yet, for all that Georges resembles Andrei in certain respects, he also possesses an impressive empathy. Early in the novel, Georges observes a boorish American attempting, solely on the basis of his race, to bully a Japanese officer into giving up his berth. “The Japanese gentlemen,” Georges observes, “either knew no English or very wisely pretended that he did not.” (The latter will turn out to be true.) Later, Georges will be appalled by a White Russian’s assertion that it was “the liberation of the serfs in 1861 that caused all the mischief.” As he points out: “...in his opposition to the liberation of the serfs he had forgotten that in ordinary circumstances he himself would not be a master but a serf...”

Empathy is a powerful thing. There are laugh-out-loud moments in The Polyglots, from the absurd name of Georges’s romantic rival (Gustave Boulanger) to wry riffs on Communism. But it’s also a novel with a profound sense of melancholy: One supporting character commits suicide in a particularly shocking fashion, and the fate of one of the novel’s most likable characters casts a grim pallor over its final pages. The conclusion of The Polyglots is not a comic archetype of either mirth or marriage; instead, it’s one of loss and departure, a sharp contrast to the earnest return that opens the book. But it’s with this devastation that The Polyglots becomes something more—not just an examination of the foibles of the upper classes, but a work which earns empathy for all of its characters, regardless of their origins. It’s all the funnier for it—and all the more moving.