During the Blitz, novelist Anthony Powell read dull books to escape the noise and terror outside. The bombs fell and he sat in bed, absorbed in the history of the Druids. Keep calm and carry on. My own experience with dull art is less heroic, more ambiguous. I’ve seen Barnett Newman’s “Voice of Fire” at the National Gallery and contemplated one man’s ability to paint an 18-foot straight red line. But then it’s dead easy to shrug and spurn and harder to be patient with strangeness. How do I know this? Inspired by Powell’s example and keen to escape the noise and terror of living in suburban Ottawa without a real job, and having exhausted all kitten memes on reddit, I promised myself an encounter with slow art, a vain exercise in self-discovery. Some people go to the gym. I spent three days reading Karl Ove Knausgaard’s fat, plotless memoir My Struggle and screening Bela Tarr’s seven-hour-and-12-minute film, Satantango which is the story of a collective farm in Hungary and which has been described, kindly, as a “glacier of cinema.”

I slept normal hours and ate Spartan meals of potato soup and stern German rye bread. I fed the cat according to his schedule and answered emails, even live-Tweeting the experience of watching the film, which neither lost me followers nor gained me a single one. In the end I learned a few things: first, that I’m a moron with a short attention span who is addicted to plot and narrative cause-and-effect, which neither My Struggle nor Satantango has much of; second, there’s truth in Pascal’s wager and its co-option by Alcoholics Anonymous: you must fake it until you make it. Boring art succeeds through attrition, and if you stop trying to figure it out, it figures itself out for you, but only if you put in the time, like a dockworker. Boring art is the spookiest art of all. It works because there’s no good reason it should.

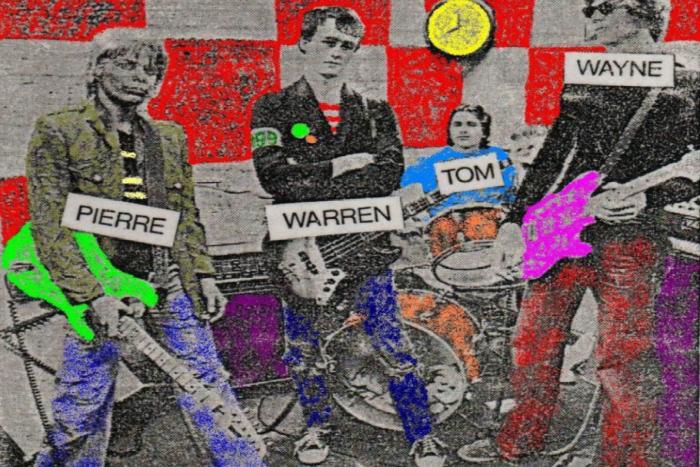

I can’t think of a book whose title is better suited to the experience of reading it than My Struggle. A smash hit in Norway, it is the 430-page memoir of a novelist to whom not much has happened. In fact, My Struggle is just the first of a six-volume memoir of a novelist to whom not much has happened, but who nonetheless describes what did happen in some detail. As a teenager he plays guitar in a shoegaze band, stumbles through a few doomed sexual encounters, gets an older friend to buy beer which he takes to a New Year’s party, in a scene that covers over 70 pages and ends (spoiler alert) with the beer being drunk at a New Year’s party. “Knausgaard seems unable to leave anything out,” says James Wood in The New Yorker.

We took our jackets off in the hall, I put my boots neatly at the bottom of the open wardrobe, hung my jacket on one of the ancient, chipped golden clothes hangers, Grandma stood on the stairs watching us with that impatience in her body she always exhibited. One hand passed over her cheek. Her head twisted over to one side. Her weight shifted from one foot to the other. Apparently unaffected by these minor adjustments she kept talking to Dad. Asked whether there was much snow higher up. Whether Mom had left. When she would be back next. Mm, right, she said each time he said anything. Right.

“And what about you, Karl Ove,” she said, focusing on me. “When do you start school again?”

“In two days.”

“That’ll be nice, won’t it.”

“Yes, it will.”

And so on. The trivia of Karl Ove’s childhood piles up, Karl Ove writes it all down. When his father drinks himself to death, the opportunity for pathos is waved aside in favour of a long account of Karl Ove and his brother Yngve scrubbing the dead man’s filthy house from top to bottom. We learn the brand names of the cleansers they use.

To paraphrase Geoff Dyer, the book is not behaving the way a book is supposed to behave. But from time to time, attention to trivia is rewarded with clues: “Sometimes I mused that if all soft feelings could be scraped off like cartilage around the sinews of an injured athlete’s knee,” Knausgaard writes, “what a liberation that would be. No more sentimentality, sympathy, empathy...” Instead of picking the easy fruit of “soft feelings” he forces a cold eye on his own mundane past, his father’s death, the yawning gap between what we expect will happen with our lives and what actually does. “Understanding the world requires you to take a certain distance from it,” he says. I found myself imagining Karl Ove on TV with Dr. Drew, encouraged to bust it out, told it’s OK to be sad and that sentimentality, sympathy, and empathy are tools for recovery, but My Struggle won’t bite: it’s in no rush for closure. I wonder if six volumes will be enough for Knausgaard.

For sure Satantango doesn’t behave like a movie is supposed to behave. Watch enough YouTube and you’ll see that even eight-year-olds understand the grammar of filmmaking and the rhythm of the cut. Meanwhile, Bela Tarr’s stubborn camera lingers on single shots for 10 or 12 minutes at a time until your eye wanders from the action, such as it is, to a fly crawling on a bottle on the kitchen table. The story is simple: villagers on a collective farm come into a wad of money and argue about what to do with it, until a mysterious man from their past shows up with his own idea, which may be nefarious. A conventional film would create the conditions for barnstorming its way to a settled conclusion, but Tarr seems less interested in how the film will end than in how it gets there—slowly, with a camera so enthralled with what it sees that it barely blinks. As in My Struggle, the film wants nothing to do with sentimentality, sympathy, and empathy: we get to know these peasants (really well) but can never decide if they’re noble, ignorant, superstitious, or capable of great sacrifice, the point being that they are all these things, as all people are, and the only way to understand this is to invest close to eight hours with them through a camera as cold as Knausgaard’s pen.

Two men sit on a bench in the hallway of a government building. They don’t speak. Minutes pass. It is a real-time account of the experience of two men on a bench. Then one of them notices that there are two clocks in the hallway and they’re both wrong. In another movie this would be significant, a fat roaring Symbol, but in Satantango, which has no symbolic agenda, it’s just a fact: this is what you get in a government building in Hungary. This is how we live here. Near the end of the film, we see a police officer dictate a report to another who types it up, and what seems at first to be a handy summation of the action of the last seven hours turns into something else: partway through the report they break for lunch. We watch the policeman fish a pickle from a jar and tear at a piece of bread while the other reads a newspaper. They eventually return to the report, but by then it’s time to call it a day. The scene lasts 20 minutes, three of which are devoted to watching the man eat. There is one edit. What looks like a climax is pure digression, and the only tension is in wondering if the idiot will get the pickle out of the jar. Sell that to Hollywood as an Act III “denouement.” The point is that it’s deliberately consistent with the tone of the last seven hours, and tone is the only thing that matters in Satantango, which only earns its value if you sit through it.

*

Here’s the problem: I’m not wired for this. I need a car chase, a wisecracking neighbor, gunplay. The seven-hour film stretched into ten, counting the number of times I paused it to attend to important matters: the soup had to be re-heated in the microwave; a pencil, which I spotted under a chair, had to be retrieved; my squash racquet, which I was sure was in the hall closet, had to be located (shelf, laundry room), despite the fact that I haven’t played in six years.

Somewhere in my cultural training I’ve bought into the idea that a contract exists between artist and consumer, in which narrative development and closure are delivered in exchange for time. In a 1934 essay, psychoanalyst Otto Fenichel says, “[o]ne should not forget that we have the right to expect some ‘aid to discharge’ from the external world. If this is not forthcoming, we are, so to speak, justifiably bored.” What happens when that right (his italics) is denied? Breach of contract. And yet there’s a tradition of art that refuses to deliver its end of the deal: Moby Dick has the equivalent of a car chase (whale chase) but spends much of its ink on zoology and the history of a deep-sea fishery; James Joyce’s Ulysses is 933 pages (Penguin paperback edition) of the trivial events of a single day. Jane Austen’s Emma is the story of one woman’s dull life in a small town, in detail. How do works that deny the consumer’s Freud-given right to stimulation through action and cliff-hanginess become masterpieces? By swapping one form of suspense (dramatic action) with another: the presentation of a world the reader has never met before. Both Satantango and My Struggle are oddly compelling because you can never know what will come next. Not much happens, but it happens in surprising, unpredictable ways. The trick is to wait out your own expectations.

My friend Greg Kelly once explained to me how Marx Brothers movies work: first nothing is funny, then nothing is still funny, and then some occult border is crossed and wham, everything is funny. And it works even if Zeppo is in the film. Why is this? I think it has something to do with patience and humility, not mine but the Brothers’: this is their genius. They are prepared to wait out my suspicion that their world is absurd and lacking in rigorous cause-and-effect, until I realize that my world is absurd and lacking in rigorous cause-and-effect, and it turns out that’s funny. The movie unfolds as if it doesn’t matter whether anyone is actually watching: the madness would happen all the same.

Boring art that follows the Marxist (as in Brothers) model humbly conducts its business without feeding your consumerist preconceptions. So in My Struggle we get pages of Karl Ove, after his father’s death, smoking cigarettes in the kitchen, fixing tea, drinking tea and smoking cigarettes on the veranda, and otherwise behaving not at all like someone in a story who’s grieving. He talks to his grandmother, the dead man’s mother, but by now she’s too lost in a fog of near-dementia. “I saw that,” he writes, “but there was nothing I could do,”

I could not build a bridge, could not help or console her, I could only watch, and every minute I spent with her I was tense. The only thing that helped was to keep moving and not to let any of what was present, in either her or the house, find a foothold.

Dull detail, more dull detail, and then wham, a flicker of insight and everything changes. This is how it is, grief. Not like the movies or novels. This is how some of us in the real world deal with crisis: by avoiding it (and here it helps to have a Nordic emotional thermostat, trust me) by constant meaningless motion and aimless day-to-day bustle, denying it a foothold. The relentless accretion of detail tells the story of a man who not only won’t but can’t stop to sum it all up in a crackerbarrel yarn. It’s not flattering, neither to the writer nor the reader, but it is real: Knausgaard’s no hero, I’m no hero, we’re just kindred meatheads who improvise on life as it happens. Unlike Anthony Powell’s experience with the history of the Druids, My Struggle doesn’t distract from the nasty but makes it all the more familiar, intimate.

So let’s say the three day marathon of Euro-dull was short on laughs. If I hadn’t set it as a task, I probably would’ve given up after an hour of Satantango and watched Doctor Who, in which highly caffeinated English people work super-hard to amuse you, which is our contractural right. But in manageable batches, say once or twice a year, there’s value in encountering a mirror of your own world, as unflattering, and dull, as that can be. You feel less alone.