When my son was four, the kids at his daycare became curious about me and his other mother. Nearly every day one of them would ask us, “Why does he have two moms?” An older girl, the sister of one of his classmates, was even more pointed: when I offered our stock response, rhyming off the different forms families can take, she cut me off and said, “Yeah, yeah. I know all that. What I want to know is how two ladies actually make a baby.” (Luckily, the bell rang and I was spared from having to stumble through a discussion of donor dads and turkey basters.)

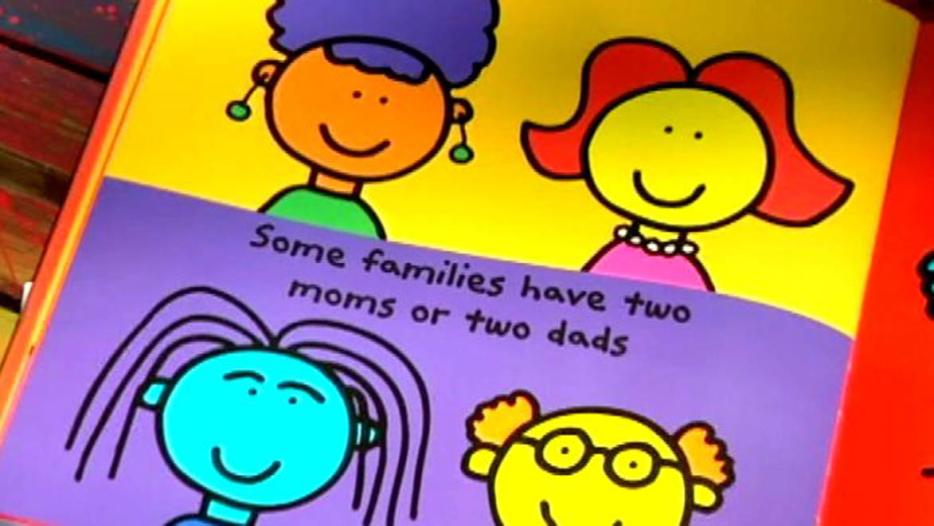

To help the teachers talk about our family’s situation, we gave them a copy of The Family Book by a kid’s author named Todd Parr. Parr writes picture books with cheery messages about tolerance and kindness, filled with scribbly, childlike illustrations. They are earnest, feel-good and goofy, with as much edge as a marshmallow—Green Eggs and Ham has more political bite. (The Family Book depicts several kinds of families, among them: families with two moms or two dads, families who adopt, families who have step-siblings, families who have pets, families who like to hug.) In other words, we figured the book was suitable for the age group and wouldn’t offend. We figured wrong. Soon after we delivered it, one of my son’s teachers, a young woman we’d had a good relationship with, explained that her religious beliefs prohibited her from talking about same-sex families. While she loved the sinner, she said, she couldn’t promote the sin.

I’ve faced bigotry and hatefulness plenty of times: a date and I were once surrounded by a group of guys who said they were going to rape us until we were straight; at the height of AIDS paranoia, I witnessed police officers pull on latex gloves to handcuff friends protesting for their civil rights; I’ve received hate mail and, once, a death threat for writing about gay issues. These experiences were terrifying, mortifying, galling. But they were nothing compared to fury and bitterness I felt when my son’s teacher refused to read the book—because this involved my child, a person to whom I am irrationally devoted and of whom I am ferociously protective. That he was in the care of someone who felt our family was illegitimate frightened me. What kind of sway would she have over him, and what kind of damage could she cause? If our son was teased for having two moms, would she protect him, or side with the bullies?

A recent story in the Toronto Star brought this episode back to mind. Louise Brown, the paper’s education reporter, wrote about conservative Christian and Muslim parents who are asking local schools to let them know when their child’s class will be discussing issues “ranging from homosexuality and birth control to wizardry, evolution and ‘environmental worship,’ so they can withhold their child from classes that contradict their religious beliefs.” Following the lead of a Greek Orthodox father in Hamilton, Ontario, who sued his local public school board for refusing to give him advance notice when his children’s teachers address issues he considers controversial (sexuality, marriage), parents can download a form letter, created by a group called PEACE (Public Education Advocates for Christian Equity). Parts of the letter are nutty—is any school board teaching about astrology and psychic powers, conducting discussions on bestiality and bondage, or advocating infanticide?—but the intent of PEACE is clear: to push a religious agenda in the public school system.

I have an instant reaction and a slower one. The former is simple: Canada is a pluralistic, secular democracy. Divorce is legal, as is gay marriage. Abortion was decriminalized long ago, birth control is widely utilized, and a significant number of Canadians live in common-law relationships. Public schools cannot ignore these realities, any more than they can ignore evolution, the existence of climate change, or the pleasures of Harry Potter books. People who want to shut out the rest of Canada, who wish to have their kids educated according to their specific religious values, should send them to private religious schools.

My slower reaction is more complicated. Because on some level, I kind of get it. At its best, education is dangerous. It exposes our kids to opinions and ideas beyond those they receive at home. There’s wonder in those moments when the world opens up to a child, when they become aware of its infinite, awesome possibilities—when they grasp fractions, understand how a seed transforms into a plant, when a novel seems to speak directly to them, or when random vocabulary words in a new language shape themselves into proper sentences. But this process, for parents, is also bittersweet; in these moments you realize that your child is becoming their own person and you are no longer their only lodestar.

So, I wonder if these religious parents don’t so much fear the teaching of unfamiliar and unwanted values as they fear their children finding these values appealing. What if the vast universe outside their own seems more beautiful? What if public, secular education inspires their kids to think differently about society and their place in it? What would that say about their children? More importantly, what would that say about the limits of their faith itself? No one wants to contemplate the failure of their belief system in the face of new wisdom and experience. And no parent wants to contend with their child’s rejection, or imagine them growing into someone unrecognizable.

The situation with my son’s daycare teacher was eventually resolved: we spoke to her supervisor, who read the book to the kids herself (soon afterward, the teacher moved out of the country). When I think back on the incident, what I remember most is not the teacher’s self-righteousness, or the betrayal we felt. What I remember is how much we liked her, how kind and thoughtful she was, and how much she genuinely seemed to like us. I wonder what acts of cognitive gymnastics she had to perform to manage two opposing ideas: her religion told her we were an abomination, but her experience—her education, if you will—taught her that we were a warm and functional couple raising a healthy, happy kid. I suspect that, just as we were afraid, she was afraid, too. Not because we were the monsters she imagined, but just maybe because we weren’t.