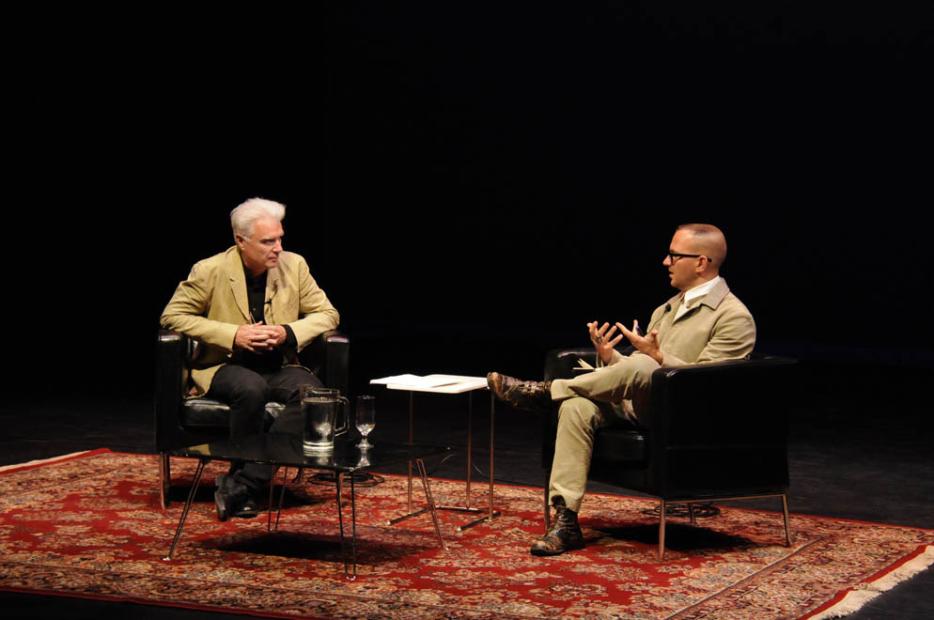

The sound was small in the big room last night, as latecomers shuffled into Harbourfront’s Fleck Dance Theatre. Underneath the muffled conversations an indistinct song played, a groove lost behind the energy slowly building in the amphitheatre, as we waited. We were there to see David Byrne in conversation with Boing Boing co-editor Cory Doctorow, the occasion provided by the publication of Byrne’s new book, How Music Works.

The book is a lush odyssey of sound mapped out on the page. It details his philosophies of performance, community and creation, a history of the shift in musical technologies, biographical notes on his work, and nuanced meditation on all of the above. In his recent review, Doctorow focused primarily on Byrne’s comments on the way that the technology of a period predetermines the shape of the art that emerges. Like Doctorow, I’m especially compelled by Byrne’s assertion that history, the history of music, is not so much one of linear progress but of culture interacting with and occasionally extending the limits of the world it’s borne of. Perhaps because of Doctorow’s background, and his particular interest in copyright law in an era digital distribution, much of their time onstage was spent discussing the disjunct between musical impulses to borrow and share, and the “crooks, despots, and lawyers,” in Doctorow’s words, who make the rules to govern our doing so.

Byrne began by introducing some erroneous notions, saying he’d frequently been asked for his opinion on sampling and downloading, as if these two concepts were linked and concrete rather than contextual. He told two stories about albums that had to be shelved for a full year post-production, waiting for certain legal hassles to conclude. One was his 1981 collaboration with Brian Eno, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, which was held back until they could get the proper licensing for the many and diverse vocal samples that the pair commingled with their own strange rhythms. The other was his 2008 collaboration, again with Brian Eno, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, where negotiations with their digital distributors stalled when Byrne wanted to keep iTunes and Amazon from encoding a DRM on the digital file, which would restrict which formats and players listeners could make use of in their desire to just hear the record.

Doctorow provided an excellent and accessible overview of the technical, logistical, and legal minutia of digital distribution, and touched on the recent efforts, like PIPA and SOPA, to further restrict access to music. Byrne had complex feelings about copyright, citing how his experience as an artist has made some lines seem a little fuzzier than others. Mostly, it seems like he just wants to be able to share good stuff and make sure that artists are supported for their work. He relayed an anecdote about a conversation he’d recently had with his 22-year-old daughter, telling her that if it were up to him the rights to his work, which were what had enabled him to support her, would go when he did rather than be handed down. She’d be on her own, but his art would be liberated for other artists to make even more of it.

They talked also about the history of recorded sound, how with each turn of the technological screw the pirates became the admirals of progress, to borrow Doctorow’s metaphor. He said it better, cracking the audience up. Byrne complimented Doctorow on a piece where he had outlined the legally copyrightable parts of a song: top line melody, baselines and harmonies, and the lyrics. But of course there’s more to music than that, more to the way a sound can fill you with feeling. He described an early memory, hearing The Byrds covering Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” as a child. The words and the melody belonged to Byrne’s parents, but there was something in the texture of that jangly guitar that cracked those elements open into something new. “That was a new world for me,” Byrne said, “and that’s not something that can be copyrighted.”

At the end of the night, during the Q&A period, a very young man called the moment back to life. He asked for a clarification, he wanted to know what the song was, the song that opened up his world. Doctorow and Byrne seemed surprised, and the audience laughed. But we all were charmed by the sight of him, writing out “Mr. Tambourine Man” on his program. He wanted to know if that was the song that started it all, if that was the track we have to thank for what David Byrne went on to give to us. Byrne paused, to think. And then he said it again: “No. It opened a door. It made me realize there was more than just my neighbours out there.”

--

Photo by readings.org